While political parties generally try and present a united front to the electorate, there can often be a significant gap between the policies supported by a party’s membership and the party leadership. Based on survey evidence in Sweden, Ann-Kristin Kölln and Jonathan Polk assess how these differences can affect the ability of parties to fight elections and how researchers can better understand the nature of intraparty conflict.

While political parties generally try and present a united front to the electorate, there can often be a significant gap between the policies supported by a party’s membership and the party leadership. Based on survey evidence in Sweden, Ann-Kristin Kölln and Jonathan Polk assess how these differences can affect the ability of parties to fight elections and how researchers can better understand the nature of intraparty conflict.

Parties’ policy proposals, manifestos, leadership and candidate selections are regularly accompanied by internal conflicts, as revealed by the media or by party actors’ own public behaviour. We need only think of Labour’s leadership election in the UK, Angela Merkel’s immigration policy, or Donald Trump’s nomination as a presidential candidate. But since parties try to conceal this as much as possible, it is difficult to know the exact extent of intraparty conflict, its facets and the coping strategies of parties.

We recently guest edited a special issue of the journal Party Politics on intraparty democracy in Europe that addresses some of these topics. Our aim was to cover a range of countries and geographic areas within Europe, as well as a broad cross-section of methodological approaches to intraparty politics. Understanding internal party divisions is particularly important in light of developments such as the UK’s decision to leave the EU, which generated several party leadership battles.

There are at least three important elements to consider in assessing intraparty politics: the various sources of data available to scholars of the subject; the steps that parties take to address and manage factionalism within their organisations; and finally, the electoral or other consequences of internal party disagreement. In our own research, we have touched on all three of these issues in assessing the political attitudes and behaviour of party members in Sweden.

Intraparty politics in Sweden

High-quality public opinion surveys are constructed to be representative of the general population. While this is critical in allowing researchers to draw inferences about a society as a whole with survey data, it often means that particular subgroups within that society, such as members of political parties, are underrepresented within these surveys. This is most problematic for countries in which a large number of smaller parties are present, such as Sweden.

Surveys of party members have existed since at least the early 1990s, but they have often been focused on particular parties or countries, used different questionnaires, and been administered at different times, all of which complicates comparative analysis. For example, despite a strong tradition of international public opinion and party research, there had never been a party membership survey in Sweden prior to our research.

Over the first half of 2015, we collaborated with seven Swedish parties and sent party-specific but otherwise identical surveys to their members. When we closed the survey in July of 2015, we had received over 10,000 responses. The Swedish Party Membership Survey (SPMS) was designed to provide detailed information on contemporary party members in Sweden and to facilitate comparison with similar surveys that are currently in the field as part of the Members and Activists of Political Parties (MAPP) project.

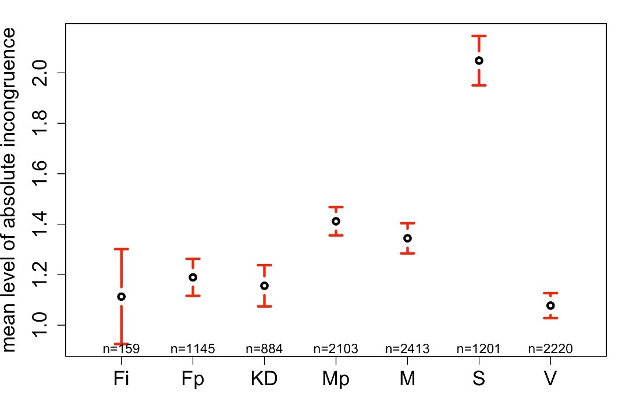

Our first analysis of these data was driven by a substantive interest in what happens if party members disagree with their party’s ideology. Figure 1 shows that this is not a rare phenomenon within Swedish parties. While around two-thirds of all party members differ ideologically in some way from their party, in some parties the absolute difference in ideological placement is larger than in others. On an 11-point left-right scale, members of the Social Democrats report, on average, a two-point ideological distance to their party, whereas members of the Left Party agree the most with their party with an average absolute distance of just above 1.

Figure 1: Absolute ideological distance of party members to their own party (by party with 95% confidence intervals)

Note: ‘Fi’ = Feminist Initiative; ‘Fp’ = Liberal People’s Party; ‘KD’ = Christian Democrats; ‘Mp’ = Green Party; ‘M’ = Moderate Party; ‘S’ = Swedish Social Democratic Party; ‘V’ = Left Party.

Drawing on A. O. Hirschmann’s framework of exit, voice and loyalty we then studied the attitudinal profile of ideologically incongruent members. What party members “voice” dissatisfaction with the party by reporting ideological disagreement between themselves and the party? And more drastically, what type of member considers an extreme form of “exit” by contemplating joining a competing party?

According to the results, members’ perceived role within the party and political interest are associated with higher incongruence. Both represent suggestive evidence for how emancipated party members with higher levels of political interest and with a more independent self-conception might be less in need of cue taking from the party. They are comfortable explicitly disagreeing with their party’s position.

Consequences of internal divisions

Some level of ideological disagreement is good, even necessary for a vibrant and effective party. Discussions and debates over policy sharpen and refine the proposals on offer to the electorate. But of course deep divisions and rampant factionalism can become existentially detrimental to the life of a political party.

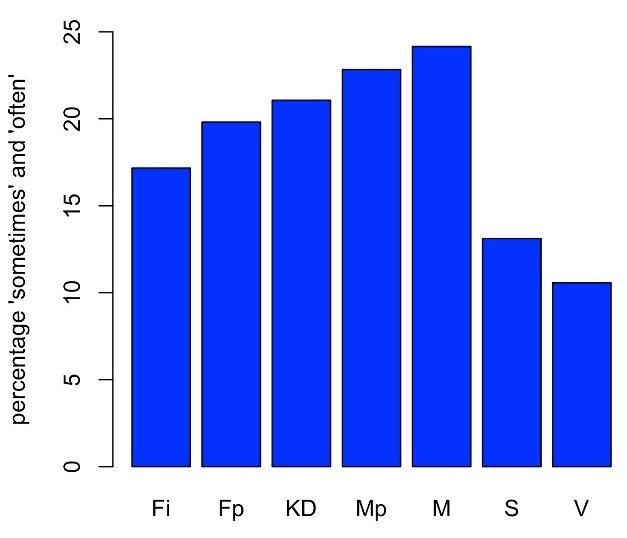

To assess this issue, we examine the extent to which ideological incongruence is connected to considerations of joining a different party. Again, the results show that a substantial number of members regularly entertain such thoughts: more than 18% of surveyed Swedish party members at least ‘sometimes’ consider joining another party, among the less congruent members the share is even higher at 22%.

Figure 2 shows the combined frequency of responses of ‘sometimes’ and ‘often’ to this question across the seven Swedish parties. Our ordered logistic regression results also confirm that ideological incongruence increases the probability that a party member more frequently considers joining another party. This means that members’ disagreement with their party’s ideological profile can have severe organisational consequences with potentially important ramifications for party competition in systems such as Sweden where electoral success is determined by small margins.

Figure 2: Thoughts of joining another party (‘sometimes’ and ‘often’ combined), by party

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying journal article.

These are just a few of the questions that we answered with the 2015 SPMS data. This new source of information also facilitates a deeper understanding of differences in intraparty politics based on party type, and can be used to investigate member-leadership congruence levels on other salient topics such as European integration. Currently, we are working with colleagues in Denmark, Finland, and Norway to develop a comparative analysis of Nordic party membership surveys, which will provide new insights on how party members act as an intermediate link in the chain of representation.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: J.A. Alcalde (CC-BY-SA-2.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2c2wP9K

_________________________________

Ann-Kristin Kölln – KU Leuven

Ann-Kristin Kölln – KU Leuven

Ann-Kristin Kölln is a Research Fellow at the Centre for Political Research at KU Leuven.

–

Jonathan Polk – University of Gothenburg

Jonathan Polk – University of Gothenburg

Jonathan Polk is a Lecturer in the Department of Political Science and Centre for European Research at the University of Gothenburg.