The party systems of Central and Eastern Europe are generally viewed as being less stable than those in Western Europe, with a greater level of volatility in terms of the parties that compete in successive elections. But how has this picture changed since 1990? Using a new dataset covering 11 countries, Raimondas Ibenskas and Allan Sikk outline some of the key factors that have underpinned splits and mergers between different parties within the region.

The establishment of democratic regimes in Eastern Europe, Latin America, South-East Asia and sub-Saharan Africa over the last three decades has led to heated debates about the functioning of party democracy across these countries. In comparison to their Anglo-Saxon or continental Western European counterparts, political parties in most of these young democracies are less stable.

Instability occurs in various ways: parties do not only enter and exit electoral competition, but they also split, merge, and form and dissolve electoral coalitions and alliances. This change matters because it raises questions about the ability of parties to perform key functions such as assuring meaningful political representation: for example, voters may be less familiar with parties’ policy positions in contexts marked by high levels of party volatility. Indeed, some analysts have even suggested that parties in young democracies are only empty shells with the actual political competition occurring between individual politicians and their factions.

In a recent study, we have addressed this debate by examining the correlation between two types of change in existing parties: change resulting from intra-party conflict that manifests itself through party splits; and change because of intra-party conflict and cooperation which is observed when parties merge or form and dissolve temporary electoral coalitions.

Our argument is that parties’ ability to structure political competition is low if we observe that intra-party and inter-party change occur together. This pattern indicates that individual politicians or their groups, by being able to cross party boundaries easily, are the main building blocks of political competition, while the role of parties becomes secondary at best. The quality of democracy is likely to suffer under this scenario because individual politicians are unlikely to provide a stable link between the electorate and government.

Change at the intra-party and inter-party levels

We use a new dataset that provides information on party change in 11 European Union member states in Central and Eastern Europe from their first democratic elections until 2015. The dataset covers parties with at least 1% of the vote in the first election of the electoral term. It includes on average 11 parties per electoral term and counts almost 800 party-electoral term dyads in total.

Our data reveals that party change in Central and Eastern Europe is common. We record 154 party splits, affecting 19% of party-electoral term dyads. In 324 cases (41% of the dyads) a party entered a new electoral alliance or merger with one or more of the other parties. Furthermore, we observe 188 cases (24%) where a party leaves an existing electoral alliance, but also 74 (9%) where it consolidates a temporary alliance into a permanent party merger. Looking at these four types of party change, we record 0.9 change events per party-in-electoral term, 2.3 per party and 10.3 per electoral term.

Notwithstanding these high levels of overall change, our analysis provides little evidence of the expected relationship of change at the intra-party and inter-party levels. More specifically, it is not so much the case that parties are unlikely to split in the same electoral term in which they form or dissolve electoral coalitions and mergers, but that parties which experience splits tend not to participate in electoral coalitions and mergers.

On the other hand, the formation and dissolution of electoral alliances and the formation of merged parties are clearly linked, although more across electoral terms than within a single period. Overall, these findings suggest that parties, rather than individual politicians or their factions, play a key role in structuring political competition in post-communist countries.

Understanding party change

The existence of this multi-dimensional pattern of change also suggests that the explanations of its individual forms are different. We explore this by looking at the correlations between party change and three factors suggested in the literature on party splits, electoral alliances and mergers – party size, the closed-list electoral system and the age of a country’s democracy.

According to this simple correlation analysis, we find that larger parties are more likely to split, while entries, exits and mergers are more likely to characterise smaller parties. The strong relationship between party size and splits is an important finding that needs to be explored in greater detail by future research. It is possible that the voters of the parent party are more susceptible to the appeals of splinter parties, thus creating greater incentives for factions or individual politicians to found new parties. Moreover, in contrast to other forms of change, splits are only weakly associated with the age of democracy or closed-list electoral systems.

With regard to inter-party change, the formation of new electoral alliances and mergers and the dissolution of existing coalitions as well as their consolidation through mergers are all less likely when a party’s electoral support is low. This finding is not surprising given that coalescing with other parties is often a matter of electoral survival for small parties. The frequency of entries, exits and mergers also decreases to a certain extent as democratic regimes mature.

However, while entries into new coalitions and mergers and exits from existing coalitions are more likely under closed-list PR, this electoral system is associated with the lower probability of the consolidation of coalitions through mergers. This supports the findings of earlier research that show that parties find it easier to reach electoral coalition agreements under closed-list systems because voters cannot disrupt the ranking of candidates established in the coalition agreement.

An extension of this logic may also explain the effect of this factor on exits from electoral alliances and mergers. Specifically, since under closed-list system the costs of founding new coalitions are lower, it is also less costly to dissolve an existing coalition by switching to a new alliance (instead of consolidating this coalition through a merger). In contrast, under open or flexible-list systems, while coalitions are less likely, once they are established, they are likely to be more durable and lead to full-fledged mergers. This factor may therefore account for the lack of a strong positive correlation between exits and mergers.

Country-specific patterns

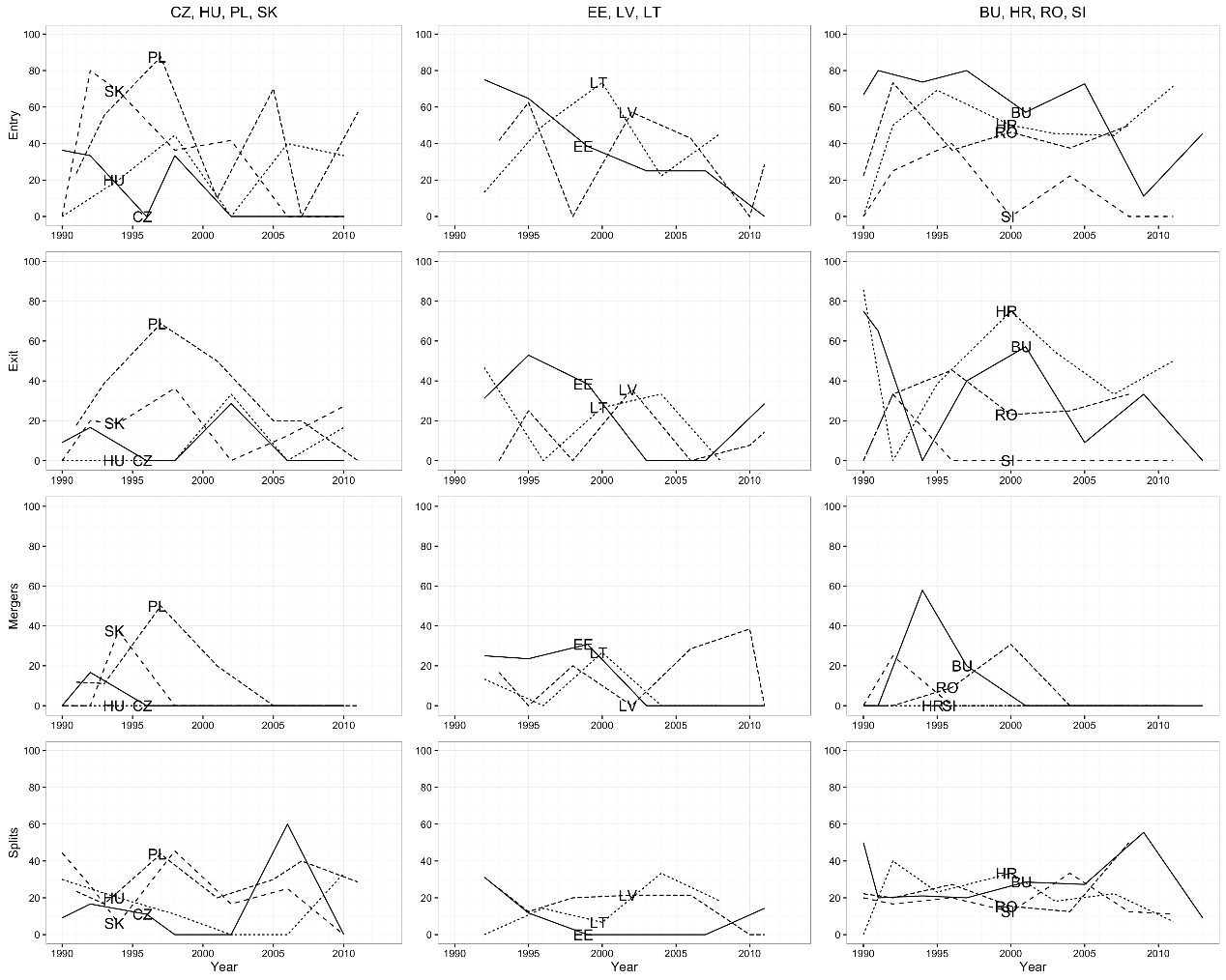

Country-specific patterns, as shown in the figure below, tentatively support these arguments about the causes of intra-coalition conflict and cooperation and new inter-party cooperation. A substantial variation in the frequency of these changes across time notwithstanding, they have decreased in most countries since the 1990s. This trend is strongest in the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary and Slovenia, which, at least in the 2000s, were characterised by relatively limited party fragmentation, few new successful parties and relatively high electoral viability of established parties.

Figure: Party change in Central and Eastern Europe (click to enlarge)

Note: The figure reports, for each electoral term, the share of parties that experienced four forms of change from the total number of parties in that term.

Larger and more viable parties could benefit less from inter-party cooperation, thus leading to a lower number of electoral coalitions and in turn fewer opportunities for exits from them or their consolidation through mergers. The remaining countries in the region were characterised by relatively high levels of entry since their democratisation. However, in the countries with closed-list electoral institutions – especially Bulgaria, Croatia and Romania – these coalitions were less stable as shown by the high frequency of exits and the presence of only few mergers in them. The countries with open or flexible-list systems, in particular Estonia, Latvia and Poland, by contrast had more coalitions turned into mergers.

The figure provides fewer insights about party splits. The variation in their frequency at the country level is limited. The trend of the decrease in time is also largely absent, possibly because the increase in party size created greater incentives for splits but this effect could have been countervailed by the increase in party institutionalisation and ideological structuration. The lack of clear patterns in the frequency of splits further calls for more cross-national research on this important phenomenon of intra-party politics.

For more information on this topic, see the authors’ recent article in Party Politics

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2dm3ESj

_________________________________

About the author

Raimondas Ibenskas – University of Southampton

Raimondas Ibenskas – University of Southampton

Raimondas Ibenskas is a Lecturer in Politics and International Relations at the University of Southampton.

Allan Sikk – University College London

Allan Sikk – University College London

Allan Sikk is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Slavonic and East European Studies at University College London.