It is easy to assume that Brexit will increase support for an independent Scotland. However looking at recent polls, Sean Swan writes that Scottish support for remaining in the EU does not translate directly into supporting independence as a means of achieving that goal. At the same time, Brexit also appears not to have had a dramatic effect on party support in Scotland.

The fact that Scotland, unlike the UK as a whole, voted decidedly to Remain in the EU attracted significant attention. The assumption was that the differing referendum results would hasten the break up of the UK. However, a careful examination of recent opinion polls reveals a more ambivalent picture.

The 2014 Scottish independence referendum (the ‘Indyref’) resulted in a 55.3 to 44.7 per cent victory for the ‘No’ to independence side. The defeated ‘Yes’ side went on to mobilise behind the Scottish National Party (SNP) and showed that while 44.7 per cent might not be enough to win a single option referendum, it was sufficient to allow the SNP to dominate the political landscape in a multiparty parliamentary democracy. In the Brexit referendum, Scotland voted 62 to 38 per cent in favour of remaining in the EU.

The EU was a major issue in the indyref with the ‘No’ side listing EU membership as one of the benefits of being part of the UK and rejecting ‘Yes’ arguments that an independent Scotland could remain in or join the EU. No less a personage than David Cameron warned the Scots that if they ‘vote for independence they are no longer members of the EU’. An opinion poll conducted by ICM for The Scotsman in July 2014 showed that support for independence increased from 43 to 46 per cent if voters thought the UK was “very likely” to leave the EU. Of course, 46 per cent is still not a majority.

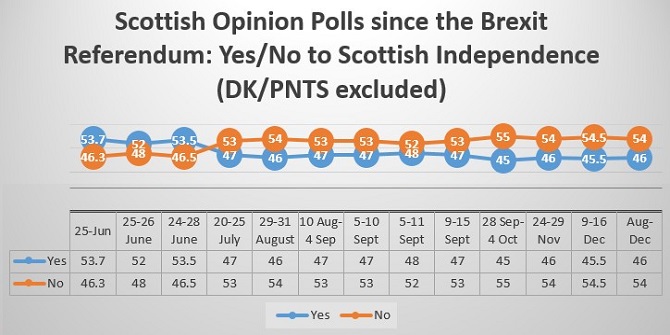

Recent polls have not shown Brexit to make a decisive difference in terms of support for independence. A September 2016 poll which posed the question ‘If a referendum were held tomorrow, on whether Scotland should leave or remain part of the United Kingdom, how would you vote?’, showed support for independence at 45 per cent, with 55 per cent for remaining in the UK, ‘the same result as the 2014 Independence Referendum’. An earlier poll, held in July, appeared to show higher support for independence, 47 per cent versus 53 per cent support for remaining in the UK; but the question asked was not about voting intentions but a more general one: ‘Should Scotland be an independent country?’. It is possible to support independence in general but not be prepared to vote for it owing to some perceived practical problem such as the currency issue.

+Excluding undecided. Data available here.

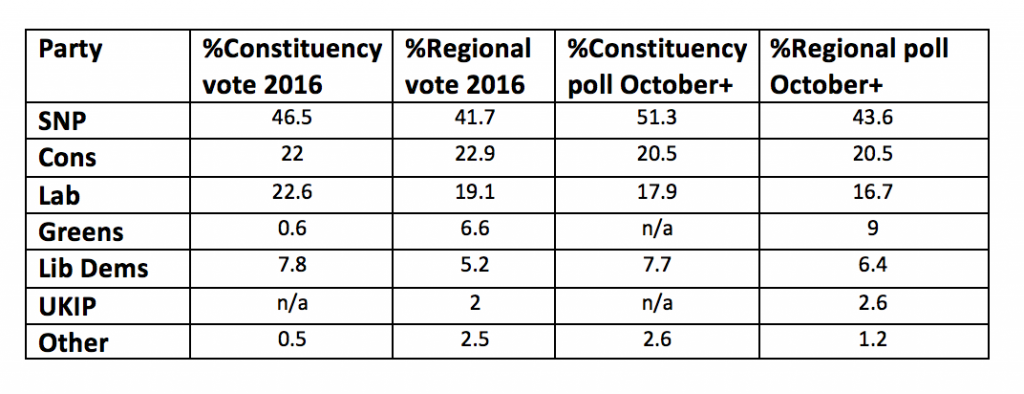

+Excluding undecided. Data available here.

Significantly, even when faced with the prospect of a ‘hard’ Brexit (no access to the Single Market), given a two option choice, 54 per cent said they would ‘rather live in a Scotland that was part of the United Kingdom that was not part of the Single Market’, compared to the 46 per cent who said they would ‘rather live in a Scotland that was a member of the Single Market but was not part of the United Kingdom’. (Here again it should be noted that we are looking at preferences, not stated voting intentions).

It is hard to disagree with the conclusion in The Herald by BMG research Director Dr Michael Turner that when it comes to independence, Brexit “is not a game changer”. Support for remaining in the EU does not translate directly into supporting independence to achieve that goal. Nor has the Brexit referendum had a dramatic effect on party support in Scotland (see table).

The future, as always, is unwritten, and this picture could change radically as the Brexit drama unfolds. A ‘hard’ Brexit followed by an economic slump, were it to happen, might result in a substantial increase in support for independence. But we are living in extraordinary times and other outcomes are possible. Linda Colley demonstrated in Britons how ‘Britishness’ was initially formed in opposition to a hostile continent; Tom Nairn, in the introduction to the 25th anniversary edition of The Breakup of Britain,attributed increasing Scottish nationalism, in part, to UK subservience to the US under Blair. Thus a UK which was asserting an independent foreign policy, (Brexit), and was faced with a hostile or intransigent EU under leaders such as Juncker, might actually result in a resurgence of ‘Britishness’ and a corresponding decline in support for Scottish independence. Such an outcome may seem unlikely, but it is one possibility.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article was first published at the LSE British Politics and Policy blog gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2eOpSLI

_________________________________

Sean Swan – Gonzaga University

Sean Swan is a Lecturer in the Department of Political Science at Gonzaga University.

Great to see an article in support for Scottish independence against UK rule keep up the great work lads ?

As a ‘yes’ supporter, I fear that a hard Brexit with economic hardship would drain Scotland of the optimism so characteristic of the independence campaign.

This is sanity. Thank you. I will share and share again. We absolutely must not go into another indyref that we will lose, or that’s it for a generation at least.

Take back your country and face the consequences no EU and no UK support bring it on Nicola Sturgeon.