François Fillon has been selected as the French centre-right’s candidate for the 2017 presidential election. But with the nomination secured, what challenges lie ahead? Marta Lorimer suggests that although Fillon’s programme proved popular with voters in the primary, he may need to broaden its appeal to have similar success in the presidential election itself.

François Fillon has been selected as the French centre-right’s candidate for the 2017 presidential election. But with the nomination secured, what challenges lie ahead? Marta Lorimer suggests that although Fillon’s programme proved popular with voters in the primary, he may need to broaden its appeal to have similar success in the presidential election itself.

On 27 November, the two-month race to become the presidential candidate of the French right ended with the victory of François Fillon, former Prime Minister under Nicolas Sarkozy. Perceived by many as a contest to select the next French president, it attracted over 4 million voters across France and wielded what was, until a few weeks ago, a completely unexpected result.

Up until two weeks before the first round, François Fillon hovered around the 14% mark, mostly battling for third place against Bruno Le Maire. However, in the last weeks of the campaign, helped by very good performances in TV debates, he gained momentum and toppled what was expected to be a two-horse race between Sarkozy and Alain Juppé. On 20 November, Fillon won the first round of the primary election with just under 44.1 per cent of the vote, and confirmed his resounding victory in the run-off against Alain Juppé, where he reached 66.5 per cent. Once again, the polls missed the real story – although on this occasion it was not entirely their own fault. As this was the first open primary of the right, it was extremely difficult to predict the turnout and profile of voters. In addition, electorates in primaries are more ‘fluid’, as they can change their minds more easily without feeling they have ‘betrayed’ the party.

Fillon’s success can be attributed to several factors, including the ability to bring together different segments of the right. His economic programme is centred on strongly liberal measures, including the reduction of civil servants by 500,000, a rise of the retirement age to 65, and an increase from the present 35-hour working week to a 39-hour one for public sector employees. While he is liberal in economic terms, he remains socially conservative, opposing measures such as plenary adoption for gay couples. A devout catholic and father of five, he is also able to appeal to the traditionally catholic right-wing electorate. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, he is perceived to be a safe pair of hands and an honest politician with no judiciary baggage.

Now that the primary is over, however, the real challenge begins. For Fillon, there are two priorities: first, bringing the party back together and second, convincing the rest of the electorate that he is the right man for the presidency. As far as the first task is concerned, the other candidates in the primary have already given him a big hand, by accepting the results of the primary with no contestation and rallying behind him relatively quickly. Several candidates had already endorsed him after the first round, and Alain Juppé’s concession speech indicated very clearly that he would not challenge Fillon’s victory.

However, he needs to get the rest of the party on board with his programme and convince voters of its value. It is in this field that he is likely to face a tougher battle. Fillon essentially has two possible avenues in front of him: he can either leave his programme broadly unchanged and go forward with what is a very right wing programme, or he can amend it to bring it closer to the centre. This represents a difficult choice. On the one hand, many of the people who voted for him did so precisely because of this strongly right wing programme, and could defect if he fails to stick to it. On the other hand, around 30 per cent of primary voters picked a more centrist candidate, and it will be necessary to appease them as well.

In addition, while the programme was very popular with those who voted in the primaries, it remains to be seen if it will be equally appealing to lower class voters. Many of the voters in the primary were affluent, middle class voters who could agree with this kind of platform, but what happens to the ones who are already struggling to make ends meet? In short, while Fillon successfully gathered the support of around 3 million core constituents, he will need to broaden his appeal significantly if he wants to become president.

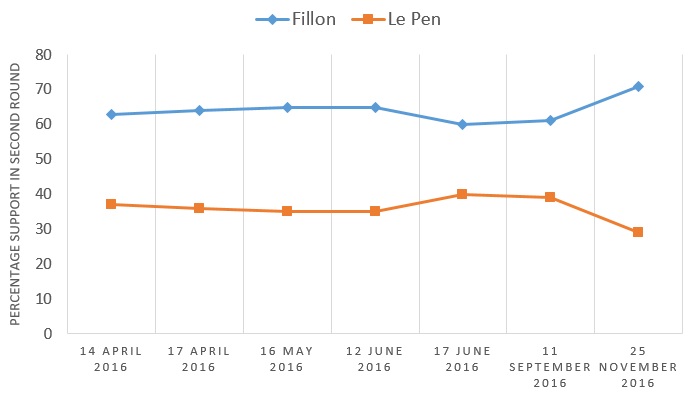

Chart: Polling on a hypothetical second round between François Fillon and Marine Le Pen

Note: Polls carried out by Ifop (14 April, 17 June), BVA (17 April, 16 May, 12 June, 11 September) and Odoxa (25 November). Don’t knows removed.

A final reflection is necessary on where this leaves the other parties in the contest. On the centre-left, Fillon’s election potentially opens a large space for a centrist candidate such as Emmanuel Macron. In fact, depending on ‘how left’ the Socialist Party’s candidate will be, there could be a broad space between him and Fillon which Macron could target. As far as Marine Le Pen is concerned, Fillon represents a challenge, but not an insurmountable one. Strategically, the Front National did not prepare for a Fillon victory, and would probably have preferred to face the more centrist Alain Juppé.

The right’s presidential candidate, in fact, poses a distinct problem for Le Pen: on social and identity issues, he is close to the Front National, but with the advantage that he has been in power in the past and is therefore perceived as ‘safer’ at the national level. This, however, could also be a drawback for Fillon, as it would allow the Front National to paint him as an ‘establishment’ candidate. His economic programme also provides the Front National with a clear opportunity to attract lower class voters who may be sceptical of his ultra-liberalism. In other words, instead of seeing the Front National focus on issues of security and culture, we may see them jump into the economic debate and present a protectionist, ‘left-wing’ economic programme.

The latest poll presenting a scenario with Fillon as the right wing candidate gave him a solid lead over Marine Le Pen, both in the first and in the second round of the election (respectively 32 per cent to 22 per cent, and 71 per cent to 29 per cent). However, considering the performance of polls in the last few years, Fillon cannot afford to rest on his laurels. The campaign ahead is still extremely long and uncertain, and it is likely to be an uphill battle for all candidates involved.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Remi Jouan (CC-BY-SA-2.5).

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2fxwemS

_________________________________

Marta Lorimer – LSE

Marta Lorimer – LSE

Marta Lorimer is a PhD candidate at the London School of Economics. She holds a degree in European Studies from Sciences Po Paris and the LSE. Her research interests include far right parties, European politics and ideas of ‘Europe’.

I think it´s gone be a close race.

Fillon is in front right now if you ask the bookmakers (François Fillon 4/11, Marie Le Pen 9/4 source: http://www.online-betting.me.uk/news/fillon-heads-the-market-in-next-france-president-betting.html )

After the first round he has to get the votes from the left, without them he won´t have a chance.

But i´m sure the pols don´t show the real strength of Le Pen, nobody votes for her but somebody has to do it if you look at the last elections;)