Scotland’s First Minister, Nicola Sturgeon, stated on 13 March that she intends to seek a new referendum on Scottish independence. Stuart Brown assesses how this second referendum campaign might play out. He writes that the Yes side would have a far more problematic economic picture to contend with than they had in 2014, but that the political argument for independence has potentially been strengthened by Brexit and the collapse of Scottish Labour.

Nicola Sturgeon has finally announced her intention to seek a second referendum on Scottish independence. Although the early indications from Theresa May are that she will reject an immediate referendum, it is highly improbable, though not impossible, that the UK government will prevent the referendum from taking place indefinitely. The debate is now turning to the timing of the vote, with Sturgeon favouring a date within the next two years and May eager to delay this to avoid a clash with the country’s exit negotiations from the EU.

But if the First Minister’s announcement is indeed the starting point for a new referendum campaign, less than three years after the last vote in 2014, how might this new campaign unfold? And can the Yes side expect to win this time around?

A mixed polling picture

Despite widespread speculation that the UK’s vote for Brexit could push Scotland out of the Union, the story of the last few months has been the apparent lack of a boost in support for the Yes side since the EU referendum. Research from YouGov demonstrates that although there is some evidence Brexit has resulted in a proportion of No voters from 2014 shifting to Yes, the EU referendum also appears to have encouraged some Yes voters to step back from their previous support for independence. The result has been a series of polls in which No has held the lead, following a brief spike in support for Yes immediately after the Brexit vote.

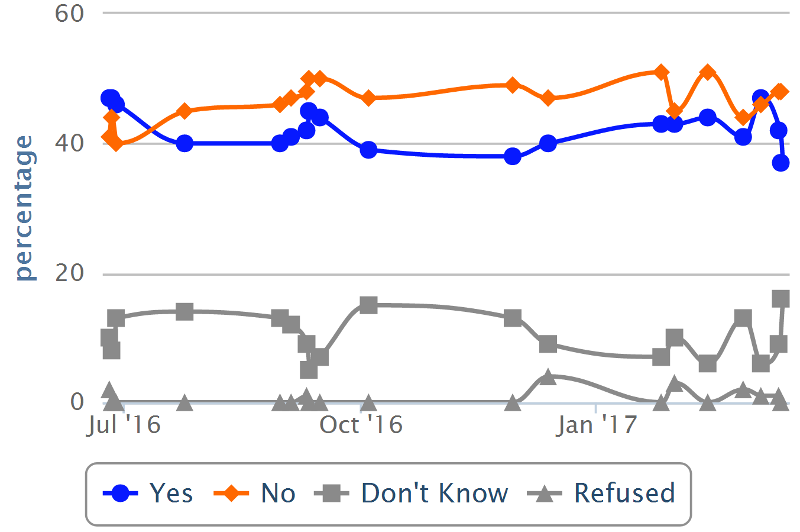

However, a poll published on 8 March by Ipsos Mori broke this pattern by reporting that Scottish voters are now split 50-50 on independence, with Yes having a lead of 47-46% in the raw figures before don’t know responses were excluded. As the chart below shows, this was the first poll since the summer in which the No side had not been ahead.

Figure 1: Results of major opinion polls conducted on Scottish independence since the UK’s EU referendum

Source: Reproduced from What Scotland Thinks

While the Ipsos Mori poll undoubtedly provided a boost for the Yes side, there is still a lack of sustained support for independence in the polling. To underscore the challenge facing the Yes side, two further polls from Survation and YouGov released on 14 March indicated a 53-47% lead for No and a 57-43% lead for No once don’t know responses were excluded. A standard that has previously been discussed is that the SNP would be confident of success in a second independence referendum if opinion polls consistently showed 60% support for Yes over a 12-month period. Clearly we remain a long distance from that goal becoming a reality.

But there are other factors that might explain why Sturgeon is willing to take the risk. The most immediate is that Theresa May’s speech in January, where she confirmed that the UK would leave the single market, may have left the First Minister with little option if she is to stand by her initial line of calling a second referendum should Scotland lose its current access to EU markets. Given the apparent reluctance on the part of the Prime Minister to grant Scotland any sizeable concessions over Brexit, Sturgeon’s credibility would have been at stake if she had failed to provide a meaningful response.

More importantly, Brexit also alters the dynamics of the campaign. A popular explanation offered for the defeat of the Yes side in 2014 was that it had suffered from status quo bias and risk aversion: namely that when push came to shove, voters who were unsure on the issue opted to stick with what they knew and backed No. But a referendum held in 2018 or 2019 would have an entirely different character. The vote could be pitched as a choice between the uncertain future of a post-Brexit UK (potentially before a deal has even been reached on the exit terms) or a future as an independent country within the EU. In essence, the timing of the vote would ensure there really would be no status quo option on the ballot paper – an argument the Yes campaign attempted to make in 2014, but with only limited success.

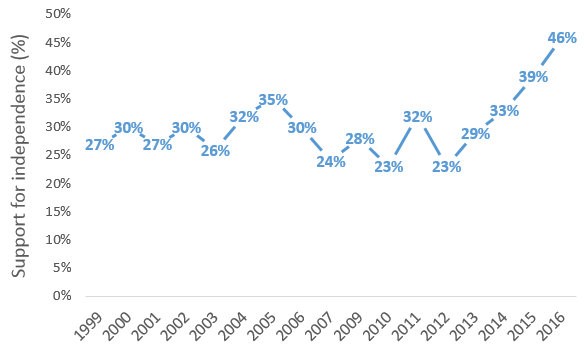

Finally, it is worth stating that the current polling situation is still substantially more positive for the independence movement than the polling prior to the 2014 referendum. This is illustrated in the long-running Scottish Social Attitudes survey, which had regularly reported support for independence (in a three option question alongside staying in the UK with/without devolution) of around 30% in the years leading up to the last campaign. The 2016 survey in contrast showed support for independence using this question format at an all-time high of 46%.

Figure 2: Support for independence in the Scottish Social Attitudes survey (1999-2016)

Note: These figures are not comparable with ordinary opinion polls as respondents are asked to select one of three choices as to how they wish Scotland to be governed: independence, devolution, or no Scottish Parliament. The 2016 report also included 16 and 17 year olds for the first time (prior to this only those 18 and over were asked). If the responses from 16 and 17 year olds are excluded then support for independence falls to 45%. Source: Figures taken from the 2016 Scottish Social Attitudes survey. There are no figures for 2008.

There is a strong belief among some Yes campaigners that they were highly successful in shifting the public toward independence during the referendum and that a relatively small swing in comparison (from the 45% who backed Yes in 2014) would be enough to secure victory the second time around. Of course, there is no guarantee a new referendum would result in a further shift toward Yes, particularly as the No campaign is likely to learn from mistakes made in the previous campaign. But there is probably still enough to convince the Yes side that while difficult, a second referendum is nevertheless winnable.

A major challenge on the economy

Aside from the polling, the Yes side’s single biggest cause for concern is the Scottish economy. Making economic projections on the potential costs/benefits of independence is extremely difficult in practice, but what is beyond question is that the economic case for independence has substantially weakened since the last referendum.

In 2014, the SNP based the bulk of its economic case on the so called ‘GERS’ figures, taken from the annual Government Expenditure and Revenue Scotland report that provides an overview of Scotland’s finances. Each year’s report contains a huge number of statistics on Scotland’s economy, but in the context of the independence debate, the figures that tend to be quoted extensively are the overall tax revenues that Scotland generates and the level of public expenditure that Scotland receives. In both cases, the GERS figures require some adjustments to determine what counts as ‘Scottish’ revenue/spending and they should therefore be taken as an estimate rather than a concrete statement of the country’s finances. Nevertheless, in 2014 GERS was acknowledged by both sides of the independence debate as providing the most authoritative picture available.

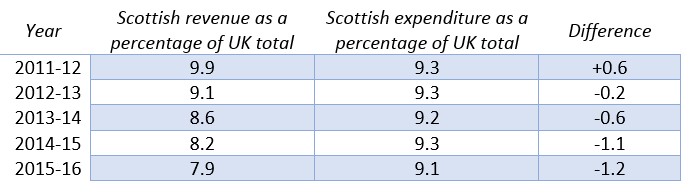

The economic case for Yes focused particularly on the GERS report covering the 2011-12 financial year. Although this might seem odd given the referendum took place two years later, there is a lag in publishing the GERS figures, so for the majority of the campaign this represented the most up to date data. It also happened to be a year that was exceptionally positive for Scotland’s financial health relative to the rest of the UK. The figures in the report indicated that with a geographic share of North Sea revenue included (which would have resulted in Scotland receiving around 94% of oil and gas revenues) the country generated roughly 9.9% of the UK’s total revenue, while only accounting for 9.3% of UK spending for the year. These headline figures were regularly used to make the argument that independence would therefore be a net benefit for Scotland in fiscal terms.

There was, of course, more to the economic case than these figures alone. The Scottish Government’s 2013 White Paper, which put forward the argument for a Yes vote, presented a number of other economic arguments, focusing in particular on the point that Scottish taxation revenues going back to the early 1980s had consistently been higher than the UK average when North Sea revenue is included (and around the same as the UK average when North Sea revenue isn’t included). But while many of these long-term arguments might still have some validity, the short-term picture has changed markedly since 2011-12, in no small part due to the collapse in global oil prices from around $110 a barrel in 2014 to closer to $50 a barrel today.

In the GERS reports released since the 2011-12 report, the balance in the relevant revenue and spending figures has shifted considerably. The same percentage figures in the last GERS report covering the 2015-16 financial year showed Scotland generating only 7.9% of UK revenue with a geographic share of North Sea revenue included, while still receiving the equivalent of 9.1% of total UK public sector expenditure. The Table below shows these percentage figures for each annual report since 2011-12 – Brian Ashcroft has previously compiled figures on the fiscal balance in Scotland and the rest of the UK going back to 1998-99.

Table: Scottish revenue and expenditure figures as a percentage of the UK total (2011-12 to 2015-16, geographic share of North Sea revenue)

Source: Government Expenditure and Revenue Scotland

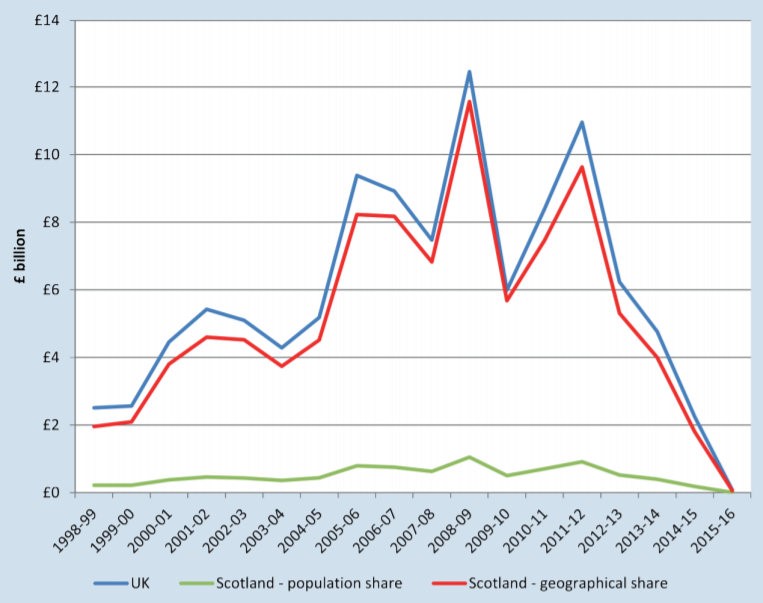

There is more to this equation than simply oil and gas revenues alone, but the fact Scotland only generated around £60 million of North Sea revenue (using a geographic share) in the 2015-16 report, when this figure has previously been higher than £10 billion (as shown in the chart below), helps explain much of the change in the overall fiscal picture.

Figure 3: North Sea revenue (1998-99 to 2015-16)

Source: Reproduced from the 2015-16 Government Expenditure and Revenue Scotland report

It is important to put these figures in the appropriate context. The effect of independence on the Scottish economy, particularly in the long-term, is far more complex than simple year on year expenditure and revenue figures can capture. Percentages like those listed above can give some idea of how the nature of Scotland’s finances have changed in relation to the rest of the UK since 2014, but they are nevertheless estimates and cannot be used to make definitive calculations about whether independence is affordable or beneficial overall.

It is also true that independence would imply fundamental changes to how money is spent in the country. Many independence campaigners argue that even if the country took a financial hit from breaking off from the UK, money could be redirected away from some areas, like defence spending, to compensate for the immediate loss in resources. Moreover, the situation can change rapidly, as the shift from 2011-12 to 2015-16 demonstrates.

Taken in isolation, these figures do not provide a concrete reason to vote Yes or No to independence. But what they do indicate is that the economic case has become substantially more challenging for the Yes side to make than it was in 2014. At the very least the pro-independence argument will require significant updating to take account of this change in circumstances.

A stronger political case?

If the economy represents a major challenge for the Yes side, the political case for independence is likely to be viewed by campaigners in an altogether more positive light. In 2014, with the coalition government between the Conservatives and the Lib Dems still in place, a common argument was to cite the fact that Scotland was being governed by a Prime Minister whose party had received only 16.7% of Scottish votes in the previous election and which only held a single MP in the country.

Three years later, the Conservatives still have one MP in Scotland, but the SNP’s unprecedented rise in the 2015 general election has left both Labour and the Lib Dems also holding just one Scottish MP apiece. While it was possible in the last referendum to draw on the participation of the Lib Dems in the coalition (the combined Lib Dem and Conservative vote share in the 2010 election being a more respectable 35.6% in Scotland) the 2015 election has sharply underlined the fact that Scotland can not only be governed within the UK system by parties that receive relatively little support north of the border, but that this may even be the norm in future elections.

This is particularly evident given the collapse of Labour. In the past, Labour governments have been extremely well represented in Scotland. Even in 2010, Labour received a sizeable 42% of the vote in Scotland at a time when its support was falling across the rest of the UK. The pattern in the years leading up to 2015 was that Scotland could appear under-represented in periods of Conservative rule, but had strong backing for the government when Labour made it into power. This is no longer the case given Labour’s support in Scotland has dropped to such an extent that it finished third behind the Conservatives in the 2016 Scottish Parliament election. And Labour’s demise will also have a direct impact on the campaign itself as the party will almost certainly avoid leading a cross-party case for No, as it did with the Better Together campaign in 2014.

Brexit, where Scotland stands to be taken out of the EU despite voting 62-38% to stay in, presents another obvious opportunity to highlight the supposed political cost to Scottish voters from staying in the Union. However, as John Curtice has illustrated, there are some clear problems with basing a new independence campaign around the EU issue as it currently divides some of those who were in the Yes camp in 2014. In symbolic terms, there is a powerful argument to be made from the fact that the decision made by Scottish voters in 2016 has been overruled by voters in the rest of the UK, but justifying a Yes vote primarily in instrumental terms as a mechanism for staying in the EU could alienate some of the voters needed to win the campaign. As such, a careful balance will need to be struck on the issue and there has already been some speculation that ‘reversing Brexit’ will not form a central part of Sturgeon’s case for Yes.

One unknown factor here is the effect of framing on the opinions of voters. Both the Yes vote in 2014 and the Leave vote in 2016 have been frequently portrayed as votes against the political establishment. Although this is undoubtedly an over-simplification, both issues now cut across one another in Scotland and this conflict will influence future voting behaviour. Some of those who chose to vote Yes in 2014 may now view the SNP, and by proxy independence, as being on the opposite side of the debate given the party’s pro-EU stance during the Brexit referendum. Indeed, in YouGov’s research, over a third of these ‘Yes+Leave’ voters had since shifted to opposing independence since the EU referendum.

The really interesting question is what will happen to these voters during another heated independence campaign in which the UK government will argue strongly for a No vote. If independence once again becomes the foremost issue on the political agenda, with the EU relegated to the background, will some of these voters come back to Yes? Alternatively, are these voters now entrenched in their opposition to independence and willing to prioritise Brexit over the issue? Given these uncertainties it is impossible to have any confidence in predictions about the result of a second independence referendum until the campaign is properly underway.

Can Yes win indyref2?

A popular idea among Yes campaigners is that majority support for independence is inevitable. Young voters are substantially more likely to support independence than older voters – the 2016 Scottish Social Attitudes survey found as many as 72% of 18-24 year olds backed independence – leading to the belief that the Yes side may merely need to wait it out until the demographic trends tip the balance in their favour.

But by taking a gamble on a second referendum now, Nicola Sturgeon has ensured the issue will be brought to a head far sooner than many had expected back in 2014. A second No vote could deal a sizeable blow to any long-term aspirations for independence – though the conventional wisdom that this blow would be fatal, as it appears to have been in Quebec, remains highly questionable.

If the Yes side is to succeed where it previously failed, it will have to navigate a far more challenging economic situation, but the developments of the last two years have also furnished the independence movement with new political and democratic arguments that they will hope can tip the balance in their direction. They will start from a position that is substantially more favourable in polling terms than they faced in 2014, but one which is still a long way short of consistent majority support for independence. It remains to be seen whether indyref2, if or when it takes place, will produce a different result.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Stuart Brown – LSE

Stuart Brown – LSE

Stuart Brown is the Managing Editor of EUROPP and a Research Associate at the LSE’s Public Policy Group. He recently published a book on the European Commission, The European Commission and Europe’s Democratic Process (Palgrave, 2016).