The leader of the Front National, Marine Le Pen, has generated controversy by denying French responsibility for the persecution of Jews during the Second World War. Hugh Mcdonnell examines the ‘grey zone’ of French collaboration with the German occupation, writing that Le Pen’s comments contrast strikingly with previous efforts to ‘detoxify’ her party.

On 9 April, Marine Le Pen, the leader of France’s Front National, denied on TV that France or the French state were responsible for the infamous Vel d’Hiv round-up of Jews in Paris on 16-17 July 1942. Corralled by French police into the eponymous cycling stadium, most of these 13,000 Jews ended up in Nazi death camps. But for Le Pen, widely expected to top the first round of the presidential elections on 23 April, “if there are people responsible, it’s those who were in power at the time. It’s not France.”

In a follow-up statement, she invoked the authority of former presidents de Gaulle and Mitterrand to insist that France and the Republic were in London during the German occupation, and that the Nazi-collaborationist Vichy regime “was not France”. Drawing on their respective inferences that Vichy was merely an aberration of the French Republic and imposter as representative of France, she holds that while individuals shared responsibility for the atrocities of the period on a personal basis; none could be imputed to France as such.

What are the implications and historical stakes of her intervention? And how is this likely to play out in the run-in to the elections? A useful starting point to make sense of the stakes of this issue is an editorial in the leading French daily Le Monde in 1992 – a period of particularly prolific and vexed public discourse about France’s Vichy past – that invoked Italian Auschwitz survivor and writer Primo Levi. This drew on his concept of the ‘grey zone’ to understand French complicity and collaboration during the German Occupation.

While Marine Le Pen has been shrewdly steering the FN away from the grey zone of complicity of Vichy nostalgia and Holocaust denial that were important aspects of FN culture, she has been less canny in summoning up De Gaulle’s and Mitterrand’s republican credentials in relation to their handling of France’s collusion during the Second World War.

Marine Le Pen’s stewardship of the Front National since 2011 has seen considerable energy invested in dédiabiolisation – or, detoxification – of the party whose origins lay in post-war fascism, including nostalgia for Vichy, unrepentant colonialism, and indeed, Holocaust denial. Jean-Marie Le Pen, Marine’s predecessor and father, has landed in legal hot water many times for denial of the Holocaust, reiterating as recently as 2015 that the Nazi gas chambers were “a detail” of the Second World War, and insisting that all kinds of patriots were welcome in the FN – fervent Pétainists (collaborationists with Vichy France) no less than fervent Gaullists.

Conspicuous in Marine Le Pen’s refurbishment of the FN is precisely the brandishing of the republican idiom that historically has drawn from anti-fascism. Adherents of French republicanism typically profess an allegiance to the values of liberty, equality, and fraternity; separation of church and state; and liberal democracy and the rule of law. Conventional wisdom in France has long posited an unbridgeable divide between the French Republic and the Front National.

Marine set out her stall as leader by immediately attacking this consensus. At her inaugural presidential speech, to the evident discomfort of some in the audience, she proclaimed the FN “a great republican political party” and asserted ownership of “liberty, equality, fraternity.” Instead of harking back to pre-Rousseau ideals, she stressed the need to recover the spirit of the Fifth Republic – a mythical golden age in which de Gaulle’s France prospered domestically and commanded respect internationally – and declared that those around her were the true defenders of the republic.

In appropriating the idea of republicanism, Marine undercut the very language used to quarantine and stigmatise the FN, and created an effective narrative vehicle to propel its message. Frontists were no longer rednecks, but guardians of secularism, the separation of church and state, and defenders of beleaguered European minorities and victimised groups. Not that this Republican message couldn’t sometimes be particularly aggressive as a bone to the party faithful – Marine’s comparison of Muslim prayers to the Nazi Occupation in Lyon in 2015, for instance.

Part of the savviness of this direction was that it could channel the melding of republican language with Frontist-style discourse, certainly by scandal-hit presidential contender François Fillon’s The Republicans, but also by President Hollande’s Socialists. Notably, this included railing against the ‘tyranny of penitence’ – Marine’s expressed rationale for her intervention on the Vel d’Hiv roundup. In this view, French society is plagued by self-castigation for historical injustices which have no bearing in reality outside the minds of domineering leftists.

If this was the impulse behind Marine’s intervention, it is unlikely to yield political capital, however. As Le Monde noted in an editorial, equivocations about Vichy might have been serviceable in the past, but are so no longer after President Chirac’s intervention in July 1995. In a departure from his predecessors, Chirac acknowledged France’s responsibility, including that of the French state, for deporting thousands of Jews to German death camps.

French memory of the Vichy years has passed through various phases over the decades. If the political legacies of de Gaulle and Mitterrand are minable for many political resources, they are scare in valuable material relating to Vichy today. That de Gaulle’s posthumous mystique has held up well is due much more to his Resistance credentials and, perhaps above all, his presiding over a period of exceptional post-war economic growth, the famous trente glorieuses. However, the simplistic post-Second World War Gaullist trope of a France of Resisters pitted against a tiny crew of collaborators has fared much less well. Even before the end of the General’s own life, his framing had come under heavy fire, epitomised by, for example, Marcel Ophuls’ documentary The Sorrow and the Pity and American historian Robert Paxton’s seminal work on Vichy France.

As this binary and self-serving framing came apart, the grey zone of Vichy returned with a vengeance. And Mitterrand, for his part, was a quintessential embodiment of the ambiguity surrounding Vichy. It was in fact in the context of the commemoration of the fiftieth anniversary commemoration of the Vel d’Hiv round-up in July 1992 that his practice of annually laying a wreath at the grave of Marshal Pétain came under sharp scrutiny.

After the ceremony, Mitterrand announced he would continue the practice before reversing course after a public outcry. In 1994 he anticipated Marine’s denial that the republic was culpable for such atrocities, refusing to apologise in the name of France. More damningly, he maintained a personal friendship with the leading henchman of the Vel d’Hiv operation, René Bousquet, as late as 1986. Mitterrand’s own youthful admiration for Pétain sparked something of a media furore in late 1994 with renewed revelations of his work within the Vichy regime before turning to the Resistance.

Mitterrand handled the affair by doubling down on obfuscation, emphasising the ambivalence of Vichy – a grey zone both in the sense that it was difficult to know what was going on, and in the sense that participation in the regime was not in itself a mark of culpability. Contrary to his earlier stubborn delineation between Vichy and the Republic, he then averred that one could in fact be working at Vichy as a sincere Republican. If Mitterrand could pull off this rhetorical greying manoeuvre, it was due in large part to his famous Machiavellian political acumen; his record, however qualified, of anti-racist initiatives whilst President; and the settling of accounts as he neared the end of his second presidential term and, indeed, his battle with cancer.

Marine Le Pen has no such assets going for her. Perhaps she might take solace from the fact that despite the media furore, the spotlight on Mitterrand’s own grey zone in his personal history had no negative effect on his approval ratings. And a much lower percentage of the French electorate has personal contact with the Vichy period today; in this vein, it is striking that the FN is scoring highest amongst 18-24 year olds for whom anti-fascist denunciations of the FN have less purchase.

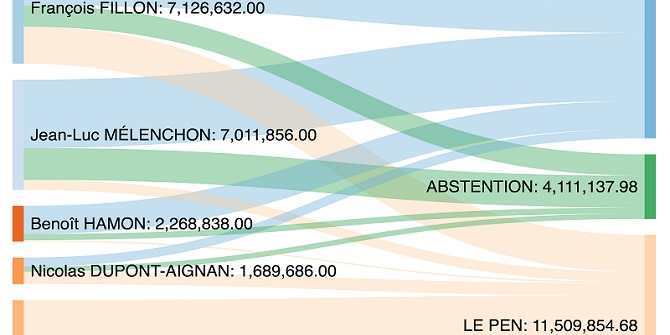

Yet, to have denied French responsibility for the Vel d’Hiv round-up in this way seems to indicate an overreaching of a Republican FN in parading a version of patriotism whereby France is a priori admirable and wrongful acts detachable in advance as un-French. Given the fragility of the detoxified ground of the party, the grey zone of Vichy would seem unfavourable terrain to stake out this position. In a presidential contest which revolves around transfer votes in the second round, her opponents will no doubt try to capitalise on this to dissuade potential FN voters between now and the election run-off on 7 May.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Hugh Mcdonnell – University of Edinburgh

Hugh Mcdonnell – University of Edinburgh

Hugh Mcdonnell is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the University of Edinburgh specialising in the history of Vichy France.