Survey evidence suggests that women in many European countries have a lower level of interest in politics on average than men do. Based on a recent study, Marta Fraile and Raul Gómez highlight that the degree of overall gender equality in a country can have a substantial impact on this ‘gender gap’ in political interest. However, this effect is largely confined to older citizens, suggesting that socialisation processes can still result in women being less interested in politics in younger age groups even in countries with high levels of gender equality.

Women in politics. Credits: Rappaport Center (CC BY 2.0)

Notwithstanding the improvements in gender equality that have taken place in European democracies, women appear to know less about, and to be less interested in politics than men. This may result in a clear disadvantage in women’s capacity to voice their political wants and needs, and to influence the political decision-making process. Increasing women’s political engagement may also have fundamental benefits for society as a whole. Research shows that strengthening the political voices of women is empirically associated with better democratic outcomes and a higher degree of development.

Gender differences in levels of political interest have traditionally been attributed to gendered socialisation processes, which promote an unadventurous political role for women. Since socialisation processes are hard to change, their existence tends to lead to a disheartening conclusion: namely, that gender equality cannot be fully achieved while these processes are still in place. Nevertheless, it is possible that the role historically fostered by gendered processes may be alleviated by public policy.

For instance, policies aimed at providing support for carers; those offering more opportunities for women to influence the political agenda; or those which promote gender-integrated workplaces regardless of the type of job people do, may eventually open up more opportunities for women to engage with politics. However, despite the progress made during the past few decades in terms of gender equality, very little is known about the potential role that this plays in reducing the magnitude of the gender gap in levels of political interest.

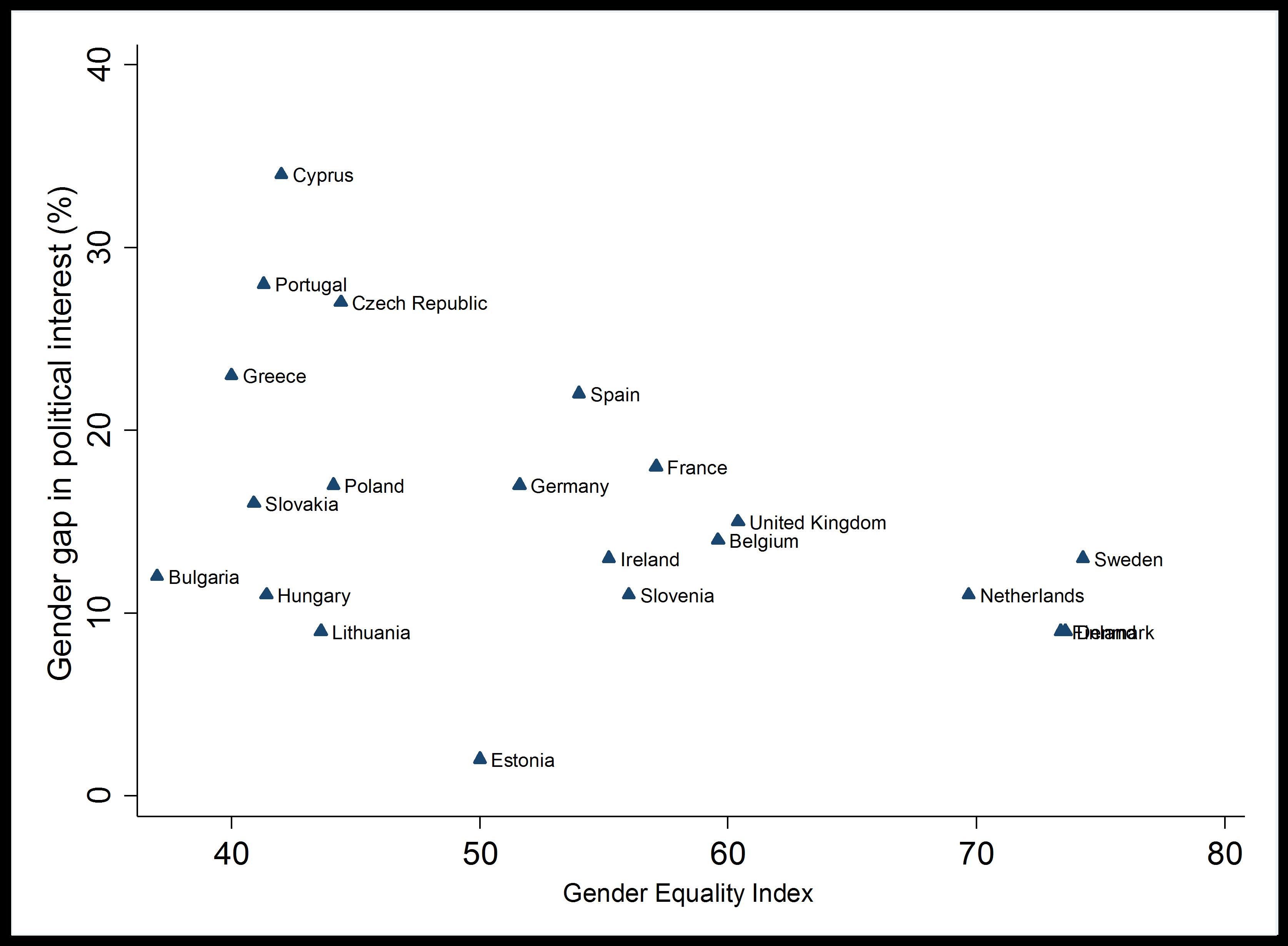

In a recent study we provide an updated assessment of the extent of the gender gap in levels of political interest in Europe. Using evidence from the fifth wave of the European Social Survey (ESS), we show that this gap is persistent across European countries. On average, declared interest in politics is 16% lower for women than for men. Figure 1 shows the distribution of the gap as a percentage across countries. Differences between the sexes range from 2% in Estonia and 9% in Finland, Denmark and Lithuania, to 28% in Portugal, 31% in Croatia and 34% in Cyprus. The gender gap remains even after controlling for differences in men’s and women’s educational attainment, material, and cognitive resources.

Figure 1 also shows that the magnitude of the gender gap appears to be related to the degree of gender equality of each country. Countries with higher scores on the Gender Equality Index (GEI), an index recently developed by the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE), are also those that exhibit smaller gender gaps in political involvement. While Nordic countries tend to score well on both measures, many of the countries with larger gender gaps in political interest (Cyprus, Portugal, Greece or the Czech Republic) are also among those with lower gender equality scores, with the exception of Estonia, which has negligible gender differences in political interest.

Figure 1: The gender gap in levels of political interest

Note: The countries at the top of the chart are those which have a larger gender gap in terms of levels of interest in politics. The countries to the right of the chart are those with higher levels of overall gender quality in society. Source: Authors’ elaboration on the ESS, 2010 and on data –from the European Institute for Gender Equality (2010)

More systematic statistical analyses clearly show a correlation between differences in political interest between men and women and the degree of socio-political gender equality in a country. As suggested above, a possible explanation is that policies promoting gender equality affect traditional roles in society by reducing the amount of time dedicated by women to family and household commitments.

However, many of the constraints that are likely to hold back women’s political engagement tend to occur or become stronger during adult life. Gender equality policies are usually designed to address gender differences between adults, especially those who are in the labour force, have children, and are married. It is possible that the potential effect of gender equality in bridging the gender gap in political interest is most acute for adult citizens. In other words, while gender differences in political interest may be similar across countries at an early age, differences between countries may widen among older adults as a result of diverging socio-political contexts.

Figure 2 presents the estimated probabilities of declaring oneself quite interested in politics for men and women, by age, and in two different scenarios: one of low levels of gender equality (GEI = 37), and one of high levels of gender equality (GEI = 74). As shown, both men and women become more interested in politics as they age. However, in contexts of low gender equality (see the left-hand side) the magnitude of the gender gap in political interest does not significantly decrease with age. In contrast, in contexts of greater gender equality (see the right-hand side of Figure 3) differences between men and women decrease with age in such a way that they cease to be significant for people in their 50s and above.

Figure 2: Probability of being ‘quite interested in politics’ by age and gender in contexts of low (left-hand side) and high (right-hand side) levels of gender equality

Note: For more information, see the authors’ longer journal article

This finding suggests that gender equality may successfully provide women with the opportunities to become more interested in politics, to the extent that in more equal countries older women have managed to close a gender gap that, unfortunately, is still present among younger people.

An implication of our findings is that the equalising effect of the promotion of gender-balanced policies might be partial since it seems confined to adult citizens. In contrast, childhood socialisation might be more strongly influenced by traditional family values that are not particularly impacted by current policies. Much remains to be done in terms of gender equality in Europe: even in countries with greater levels of gender equality women do not yet enjoy the same position as their male counterparts. Achieving gender equality is not an easy task and will take a considerable amount of time.

Indeed, public policies can make a difference when it comes to the persistence of the gender gap in political engagement, and that is very good news. However, until a complete gender balance is reached, childhood socialisation may continue to be gendered even in countries with higher levels of gender equality. Gender balance requires a revolutionary change in the way people work and the way they raise their children, so that men and women are equally able and willing to participate in both the private and the public sphere.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

well to ponder on these issues when deciding when the time is right to claim government responsibility.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article has also been published in Spanish at Agenda Pública. The article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Marta Fraile – EUI & CSIC (IPP)

Marta Fraile – EUI & CSIC (IPP)

Marta Fraile is a Research Fellow at the Spanish Scientific Research Institute (CSIC) and a Senior Researcher at the European University Institute (EUI).

Raul Gómez – University of Liverpool

Raul Gómez – University of Liverpool

Raul Gómez is a Lecturer (Assistant Professor) in International Politics at the University of Liverpool.

The idea of “gender inequality” based on the number of employees/managers/politicians is flawed – especially when it comes to politics.

It presupposes that everyone has an “identity” as part of a group. Worse it assumes that everyone has only one “identity” – in this case around gender.

Put simply, if gender defined political outlook and priorities, then surely there should be a “Female Party” and a “Male Party”?

Alternatively, there are many men who would mcuh rather support the politics of Teresa May or Angela Merkel rather than their male opponents.

Similarly there will be women who prefer the policies of male alternatives over those of a female.

As long as the selection process is fair, we should not concern ourselves so much if one sex chooses not to get involved in politics.

If so, then surely we should be bothered that women are over-represented in primary schools and midwifery ?