Opinion polls suggest Emmanuel Macron will win the second round of the French presidential election, but given the surprise results in the UK’s Brexit referendum and the 2016 US presidential election, how certain can we be of the result? Outlining findings from a new prediction model, Vuk Vukovic and Ilona Lahdelma discuss the precision of French pollsters in calling the first round, and why their survey predicts a narrower race than most opinion polls, with Macron still emerging on top.

Opinion polls suggest Emmanuel Macron will win the second round of the French presidential election, but given the surprise results in the UK’s Brexit referendum and the 2016 US presidential election, how certain can we be of the result? Outlining findings from a new prediction model, Vuk Vukovic and Ilona Lahdelma discuss the precision of French pollsters in calling the first round, and why their survey predicts a narrower race than most opinion polls, with Macron still emerging on top.

The first round of the French presidential elections, surprisingly, went exactly as expected. The outcome suggested by the pollsters was that Macron and Le Pen would enter the second round, separated by a small margin of around 1-2%, closely matching what actually occurred in the vote itself. The uncertainty regarding the outcome, however, was much greater. A week before the election, headlines everywhere were suggesting a four-way tie with each of the candidates likely to enter the second round.

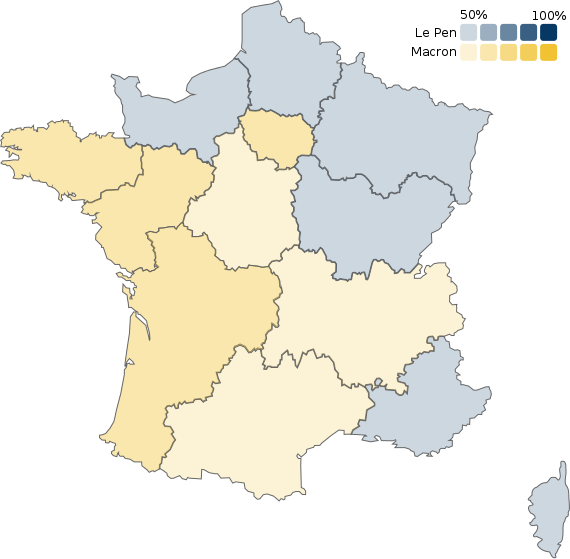

The first round results, illustrated in figure 1 below, did indeed show a highly divided France. On the one hand, there is the France of the winners of globalisation: the urban clusters of Paris, Bordeaux, Lyon, Rennes and Strasbourg, with educated, internationally-oriented citizens, working in the fields of finance, business, or technology, with clearly pro-Europe and pro-trade views. On the other hand, the de-industrialised North and the South-East, areas coping with immigration and job losses, have seen increasing support for the Front National over the past decade.

Figure 1: Map of support in the first round of the 2017 French presidential election

Note: Areas shaded in dark blue were those in which Marine Le Pen won the highest share of support, yellow areas represent areas where Emmanuel Macron placed highest, red areas show support for Mélenchon, and light blue areas for Fillon.

Interestingly, Macron and Le Pen did not manage to penetrate the citadels of the Left and Catholic France. Mélenchon did well in the traditionally leftist South-West and Fillon among the traditionally Catholic voters of the Mid-West and South-East areas of France. However, in the greater Paris area it was interesting to see that Macron managed to get votes both from the traditionally right-leaning affluent Western areas and the poorer Eastern and Southern suburbs, demonstrating that his “not left but not right-wing” policies do manage to cross traditional partisanships. This suggests that what matters in these elections are class, income, and a person’s view of the current economic system, rather than traditional party linkages.

How did the pollsters do?

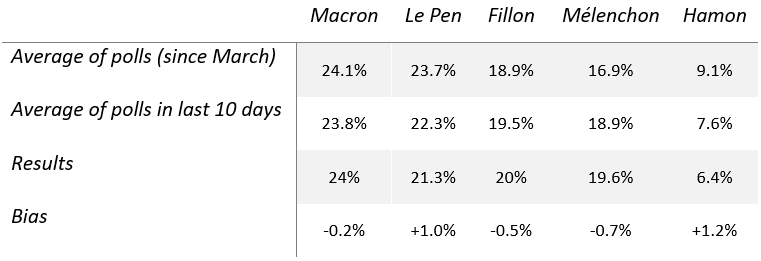

Table 1 shows the weighted average bias of all French pollsters. The results are laudable, given that the average of polls was correct within a single percentage point for all the candidates. The polls may have slightly overestimated Le Pen and Hamon, and underestimated, again only marginally, Macron, Fillon, and Mélenchon.

Table 1: Opinion polling and the actual result in the first round of the 2017 French presidential election

Note: Compiled by authors.

In an election as close as this one was, this is remarkable precision. Particularly since they correctly identified the trend which carried on until election day. This trend was a marginal rise for Macron over Le Pen since mid-April, as well as a large increase in support for Mélenchon after the debates (and a consequential decline for Hamon as he lost the support of Left voters), and finally a gradual stabilisation for Fillon following his scandals. Even in the last few weeks, the polls got the trends right – both Fillon and Mélenchon were closing the gap behind the two front-runners.

What does the first-round precision of the opinion polls tell us about the outcome in the second round? Prior to the first round, all polls suggested that any candidate that went against Le Pen in the second would secure a 15 to 20 percentage point margin of victory against her. The consensus was that, just like 15 years ago, the ‘front républicain’ would rally against Le Pen in the second round and produce an overwhelming victory for the opponent.

The combinations of how the voters will re-align have already become apparent. Many are estimating slightly higher abstention rates, particularly among Fillon and Mélenchon voters. Hamon voters are more or less all projected to go to Macron, Fillon voters will split in three-ways (about 40% for Macron, one third for Le Pen, and one third will abstain), whereas Mélenchon voters are most likely to abstain from the second round (or cast a blank vote). Adding this up, it seems like this is Macron’s race to lose.

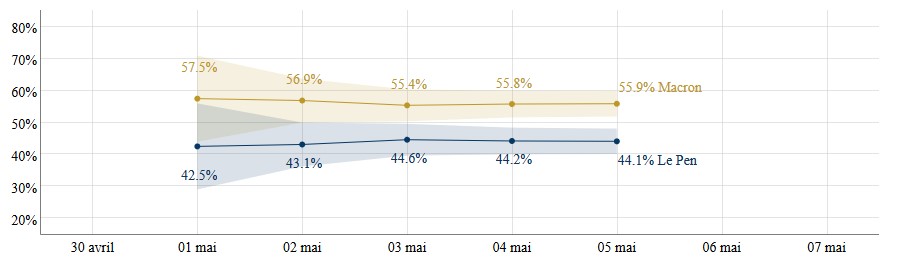

The current average of all polls after the second round stands at 60.7% for Macron to 39.3% for Le Pen (with a slight narrowing of the trend before the debate and a divergence after it – shown in figure 2 below). Given the success of the first-round polling one would assume that making a second-round prediction would not be too difficult. However, the fact that the second round involves two candidates outside of the traditional mainstream parties means it could potentially be more difficult to make precise predictions.

Figure 2: Opinion polling for the second round of the 2017 French presidential election

Note: The red line indicates the first round of the election.

The main factor that could play against Macron is the abstention rate, which promises to be at a record high in these elections. Already the first round had fewer votes (an abstention level of 22%) than five years ago (20%). The proportion of blank votes has also risen from the first round of the previous presidential election (1.9%) with 2.6% of cast votes being blank on this occasion. Blank voting was especially strong in the parts of France where both Le Pen and Macron did well in the first round and in the overseas domains where Mélenchon was the winner.

This illustrates two things: first, both Macron and Le Pen have more potential votes in these parts of France than what they have mobilised so far, and second, areas that voted for Mélenchon in the first round are prone to abstention, suggesting that there will not be a clear overflow of votes from Mélenchon to Macron. Mobilising these voters could very well be a determining factor in the election.

Le Pen’s votes come from the lower income strata that usually correlates more with higher abstention. Macron’s more educated and urban voters come from the upper income strata, but Le Pen’s voters are more committed than Macron’s supporters. Both candidates need Mélenchon’s votes and how these votes will be cast remains a mystery – not only because of the candidate’s ambiguity regarding his own stance, but also because we have yet to see how effective Macron and Le Pen have been in appealing to these voters.

Our survey

To predict the final result, we have put together a survey – Oraclum’s Bayesian Adjusted Social Network (BASON) Survey – which is based on an internet poll. It uses social networks between friends on Facebook to conduct the survey, asking the participants to express: 1) their vote preference; 2) what percentage of the vote they believe their preferred choice will get; and 3) how likely they think other people will estimate that either Le Pen or Macron will win. This is essentially a wisdom of crowds (citizen forecaster) concept, the idea of which is to incorporate wider influences from peer groups that shape an individual’s perception over who is more likely to win in his or her local area.

In addition, we adjust our participants’ forecasts for groupthink – how likely they are to be biased due to their friendship networks or their information sources. In many cases, information from likeminded friends or media can create a distorted perception of reality. To overcome this, it is necessary to measure how much individuals within the crowd are diverging from the opinion polls, as well as from their internal networks of friends. This is why we use social networks to capture the groupthink influence of friends, and adjust the initial predictions given by each participant. The end result is a very precise prediction: it guessed, within a single percentage point, all the major US swing states in favour of Trump, as well as the Brexit referendum.

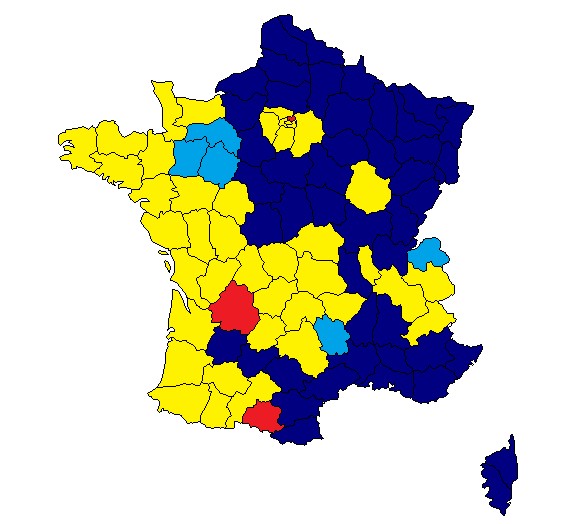

The final results of our prediction survey suggest a slightly tighter outcome than what the polls are currently suggesting. As shown in the figure below, we have Macron at 55.9%, and Le Pen at 44.1%. Our survey has at all times been a bit more conservative and has, unlike all the other polls, consistently estimated a narrower gap between the candidates. There is a regional variation as well. We predict Macron to take all of the Western and central regions as well as Paris (Ile-de-France) and the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region. Le Pen will most likely win in Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur and in Corse, and will probably come on top in the North-West.

Figure 3: Map of predicted results

Note: Map reflects the authors’ predicted results, with a majority for Le Pen in a particular region shown in blue, and a majority for Macron shown in yellow.

However, just like the polls, our survey has never brought Macron’s victory into question. The issue is only the margin of victory and how precise our prediction will be compared to the average of the polls.

Figure 4: Overall vote share prediction

The blue and yellow zones around the lines show the average errors for each candidate’s predicted vote share. At this point the errors are around 4 percentage points in each direction. This suggests that the overall likelihood of a Le Pen victory is below 1%. Unless something highly unexpected occurs on Sunday, Emmanuel Macron should be the next President of France.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. The results of the survey can be accessed here and the authors kindly thank everyone who participated.

_________________________________

Vuk Vukovic – University of Oxford

Vuk Vukovic – University of Oxford

Vuk Vukovic is a DPhil student in Politics at the University of Oxford and the Director and co-founder of Oraclum Intelligence Systems (together with Dr Dejan Vinkovic and Prof Dr Mile Sikic).

Ilona Lahdelma – University of Oxford

Ilona Lahdelma – University of Oxford

Ilona Lahdelma is a DPhil student in Politics at the University of Oxford specialising in European politics and political behaviour.