Emmanuel Macron’s La République en marche (LREM) are set to win a large majority of seats in the second round of the French legislative elections on 18 June. But perhaps the biggest story from the first round was the low turnout, with abstentions passing the 50 per cent mark. Alexandros Alexandropoulos suggests that declining turnout in French legislative elections can be traced as far back as the 1970s, and that with the electoral path considered to be futile by many French citizens, the country’s political tensions may well be expressed via the streets instead.

Emmanuel Macron’s La République en marche (LREM) are set to win a large majority of seats in the second round of the French legislative elections on 18 June. But perhaps the biggest story from the first round was the low turnout, with abstentions passing the 50 per cent mark. Alexandros Alexandropoulos suggests that declining turnout in French legislative elections can be traced as far back as the 1970s, and that with the electoral path considered to be futile by many French citizens, the country’s political tensions may well be expressed via the streets instead.

In the first round of the French legislative elections on 11 June, Emmanuel Macron’s newly formed party, La République en marche (LREM), gained a comfortable majority. But this was not the most newsworthy story from the election.

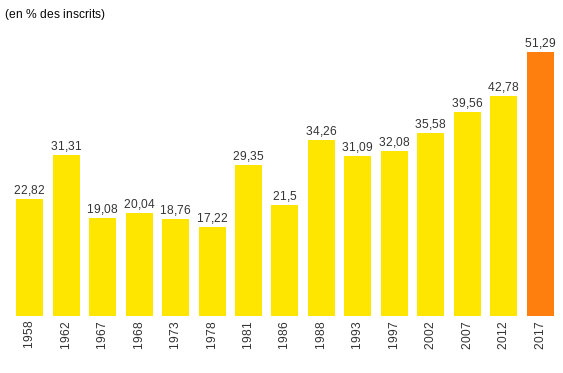

The election will go down in the history books as the first time that a majority of French voters chose abstention. It was a remarkable event that will affect the politics of one of Europe’s biggest economies at a time when the continent and its institutions are still in turmoil. But this record only follows a downward trend that started as far back as the middle of 1978, as shown in the figure below.

Figure 1: Percentage of abstentions in the first round of French legislative elections since 1958

Source: francetvinfo / Ministère de l’intérieur

The rise of abstentions after 1978 coincided with the early stages of the ‘financialisation’ of the French economy: a process that saw financial investment expanding rapidly, with even non-financial corporations, such as industrial companies, turning decidedly towards financial investment.

The result was a situation where the over-expanded French financial sector became central for the overall performance of the economy and enjoyed significant leverage on consecutive French governments. Manufacturing and other forms of productive investment entered a period of decline in favour of a model of moving French production overseas and re-investing profits in the French financial sector. The only problem with this model was that the financial sector is simply not as labour-intensive as manufacturing. Employment levels received a large blow and the surplus offer of labour brought about downwards pressures on salaries and consumption.

Alongside the financialisation of the economy, the country also entered a period of low growth, low income rises, asset bubbles, increased inequalities and a tendency of voters toward abstention. Whether these economic conditions directly contributed to the downwards trend in voter turnout in French legislative elections is difficult to say, but what is beyond question is that these conditions tore the fabric of French society apart. Rising inequalities and worsening conditions in the job market led to social disillusion. Urban zones of poverty and exclusion emerged in France’s urban centres: the infamous banlieues with their concentrated poverty and unemployment. These areas provided the ideal setting for citizen unrest, riots, and even the radicalisation of a small part of French youth.

French society is still feeling the toxic effects of this process, but voters have consistently been denied the opportunity to express their dissatisfaction at the ballot box. Parallel to the process of financialisation has been a shift toward policy convergence among the two main political forces, the French centre-left and centre-right. This has led to a series of different governments of different ideologies implementing very similar policies, leaving many voters unheard and unrepresented.

‘Consensus politics’ has been vital for providing a stable environment for the easily-panicked and volatile financial investment on which France has become dependent for growth. But it has left voters feeling that whatever choice they make, they will get the same outcome in terms of policy. To give just one example, in the 2017 elections, voters in the 18th circonscription of Paris thought that they were being given the option of backing either the former Socialist minister Myriam El Khomri – who introduced the infamous labour law under Hollande’s government – and Conservative Pierre-Yves Bournazel. There was no official candidate from Macron’s party, until a tweet announced that both candidates would be joining Macron’s parliamentary majority if they win in the second round.

Democracies in crisis

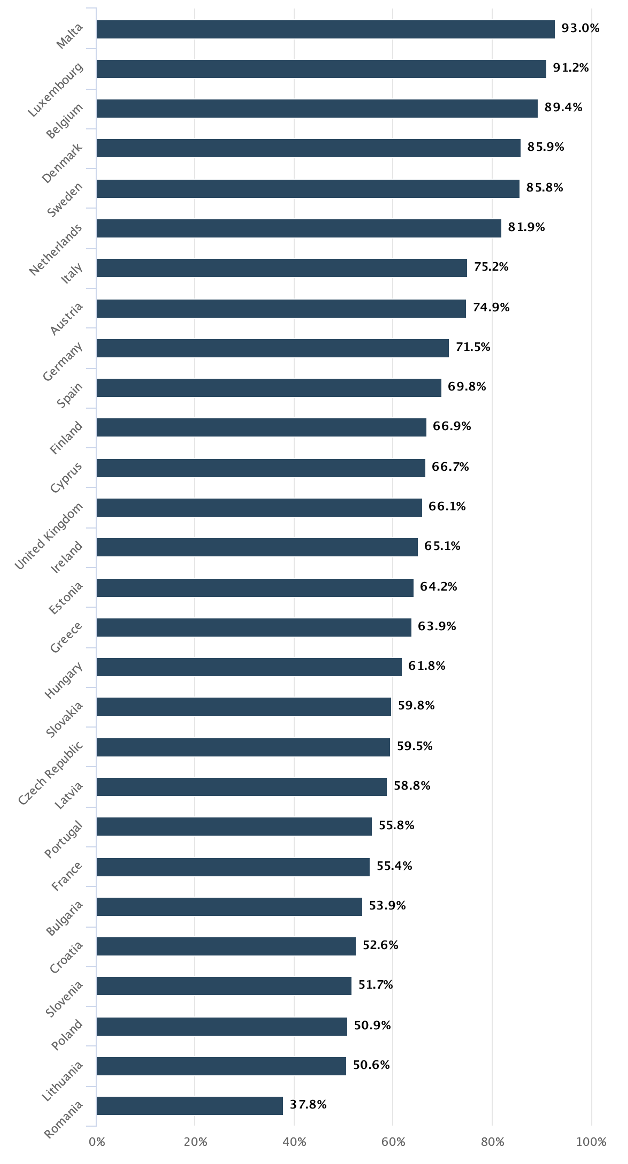

Before the 2017 elections, France already ranked fairly poorly when it came to turnout in parliamentary elections, as compared to its EU partners (see Figure 2 below). French rates of abstention are higher than in countries such as Greece, Portugal and Spain. Like these three countries, France has also been engulfed in the Eurozone’s sovereign debt crisis, the only difference is that it is yet to feel the full impact of the austerity policies put forward as a solution for the crisis.

Figure 2: Turnout in EU countries (most recent parliamentary election)

Source: idea.int

In a previous article, I discussed why Macron’s economic policies will likely be centred around austerity; facing fierce competition from the German export industry – which is benefiting from lower salaries and unit labour costs – France has been building a worrisome trade deficit with Germany. Within the Eurozone, France cannot use the tool of monetary policy to rebalance trade with Berlin and it is thus forced to borrow to compensate. It is a tragic repetition of the Spanish, Portuguese and Greek scenario.

Macron’s enthusiastic endorsement of the Eurozone and Berlin’s vital interests in retaining the enormous trade surplus it has achieved mean that the only way he can finance France’s participation in the euro is through deep cuts in salaries, employee rights and benefits. The first measures are likely to be the end of the 35 hour working week and increasing the retirement age, along with cuts in public spending. The new President will look to bring salaries and labour costs down as well as to move more resources from welfare toward servicing the sovereign debt.

These policies will likely lead to a rise in unemployment, a drop in consumption and recession. And they will signal the end of the post-war French social model. Academics and commentators friendly to Macron are already hinting that these austerity policies are a priority and are calling for him to “face down the street protests”. It was only few months ago when we saw in the press numerous cases of the French riot police using excessive violence against citizens demonstrating against Hollande’s austerity measures. The never before seen levels of abstention are going to make these measures even more controversial.

Given the high levels of abstention, it remains to be seen whether French citizens will seek other avenues to make their voices heard, such as by following the Greek and Spanish example of creating citizen assemblies like the Indignados and the ‘Movement of the Squares’. It also remains to be seen how increased disillusionment with politics impacts on other areas, such as the persistent racial tensions that exist in French society – particularly when the police force that will be called to ‘face down’ demonstrators has previously faced accusations of brutality and racism. One thing is for certain; with the electoral path considered futile by many French citizens, France’s political tensions are likely to be expressed via the streets.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Alexandros Alexandropoulos – LSE / Sciences Po

Alexandros Alexandropoulos – LSE / Sciences Po

Alexandros Alexandropoulos is an Associate Academic at the LSE and a researcher at the European Research Network on Social and Economic Policy (ERENSEP). He has taught at Sciences Po Paris and was a Policy Expert for the Hansard Society.