Last Sunday’s German federal elections marked a significant break in Germany’s post-war history. For the first time since the immediate post-war period, a far-right party entered the Bundestag. With 13% of the seats, the populist anti-immigration party, Alternative for Germany (AfD), has become the third largest party in the German parliament. A key to the success of the AfD was its ability to mobilise previous non-voters to turn out, write Julian Hoerner and Sara Hobolt.

Last Sunday’s German federal elections marked a significant break in Germany’s post-war history. For the first time since the immediate post-war period, a far-right party entered the Bundestag. With 13% of the seats, the populist anti-immigration party, Alternative for Germany (AfD), has become the third largest party in the German parliament. A key to the success of the AfD was its ability to mobilise previous non-voters to turn out, write Julian Hoerner and Sara Hobolt.

Populist right-wing parties have become a permanent feature of parliamentary politics in most other European countries, however, the success of the AfD is of significance in a country more acutely aware of the dangers of right-wing extremism. For decades, it was part of the raison d’état of the German federal republic to keep far right parties out of parliament. While some radical right-wing parties have experienced moderate success in local and regional elections in Germany, no far right parties had been elected to the Bundestag since the immediate post-war period.

The AfD’s electoral success is all the more remarkable given that the party has continuously made headlines with its infighting and cases of xenophobic language among its senior members. Founded in 2013 in opposition to further Eurozone bailouts by liberal-conservative economists, the AfD has since moved further to the right, and the party campaigned primarily on an anti-immigration and anti-Islam message in the run-up to the 2017 election.

How did the AfD manage to become the first far right party represented in the German Bundestag in recent history? A large part of the explanation lies in the opposition to Merkel’s highly controversial decision in 2015 to open Germany’s borders to hundreds of thousands of refugees. More generally, the AfD voices anti-immigration and anti-EU sentiments that are shared by a segment of German voters, but rarely expressed by parties in the German parliament.

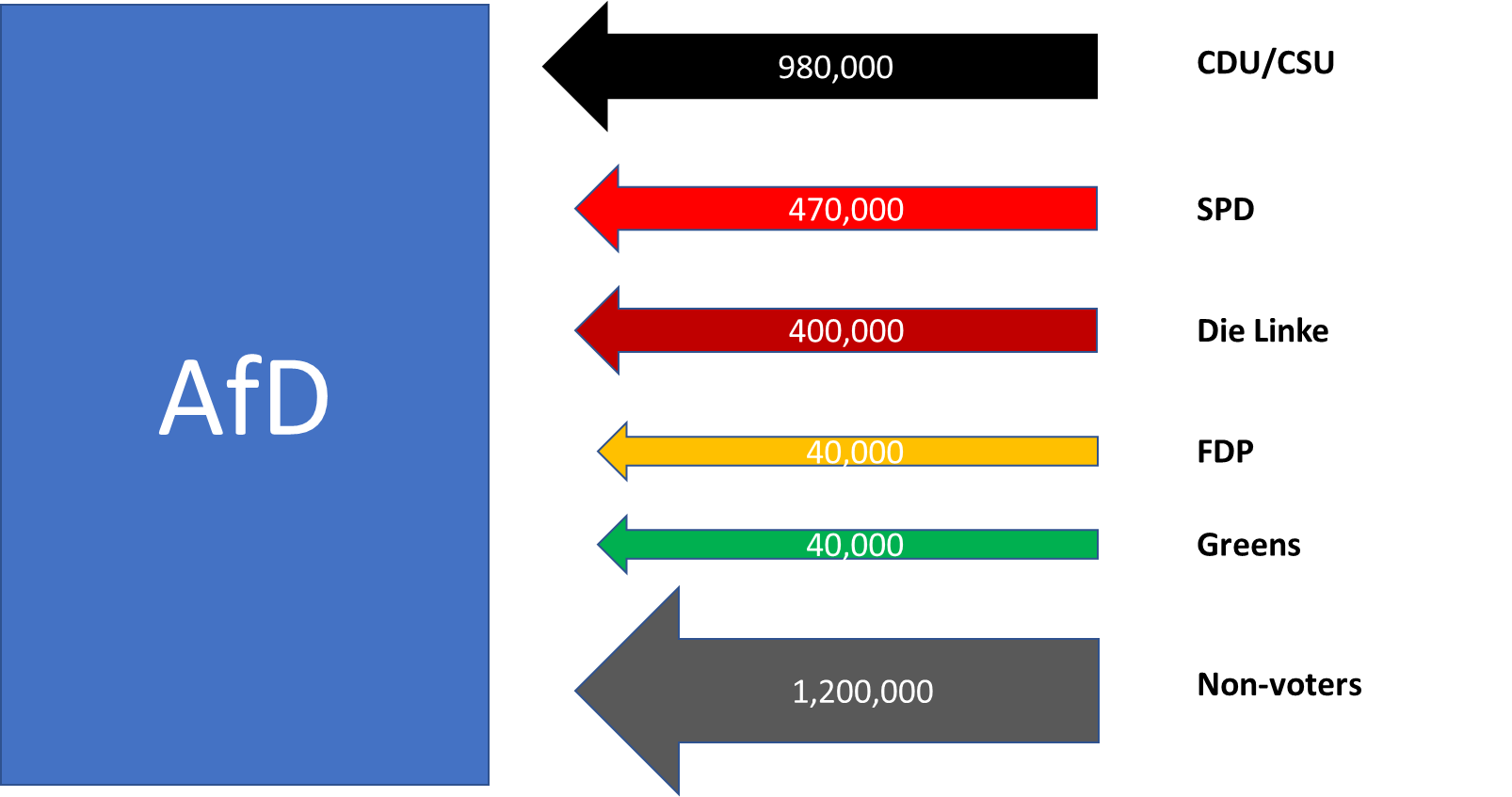

A first look at the exit polls can help us to better understand the election result. A significant number of voters switched from the centrist CDU and its Bavarian sister party, the CSU, to the AfD. It also attracted many voters who previously voted for the centre-left SPD, and most surprisingly perhaps from the far-left Die Linke. However, the largest number of new AfD voters did not cast a ballot in the previous federal elections. Far from just attracting disgruntled voters from other parties, the AfD was also able to mobilise a significant number of previous non-voters.

Figure 1: Shift of voters to the AfD in the 2017 German federal election

Note: Data from Infratest dimap

What are the reasons behind the ability of the AfD to mobilise non-voters? As part of the European Research Council-funded EUDEMOS research project, we have examined the impact of expansion of political choice on turnout in elections. We argue that expansion of choice – in this case on the right of the political spectrum – can boost turnout, in particular among voters with similar views. We have examined this more systematically by analysing the effect on turnout of the entry of the AfD in German regional elections. This focus on regional elections gives us additional analytical leverage since it allows us to compare elections in which the AfD was on the ballot with those where it wasn’t.

For our quasi-natural experiment, we analysed German regional election surveys since 2010 until the present using data from the German Longitudinal Election Study (GLES), pooling the surveys in two groups, one without the presence of the AfD and one with the AfD. This comparison of these two sets of regions shows that when the AfD is running, turnout is generally significantly higher among voters across the ideological spectrum.

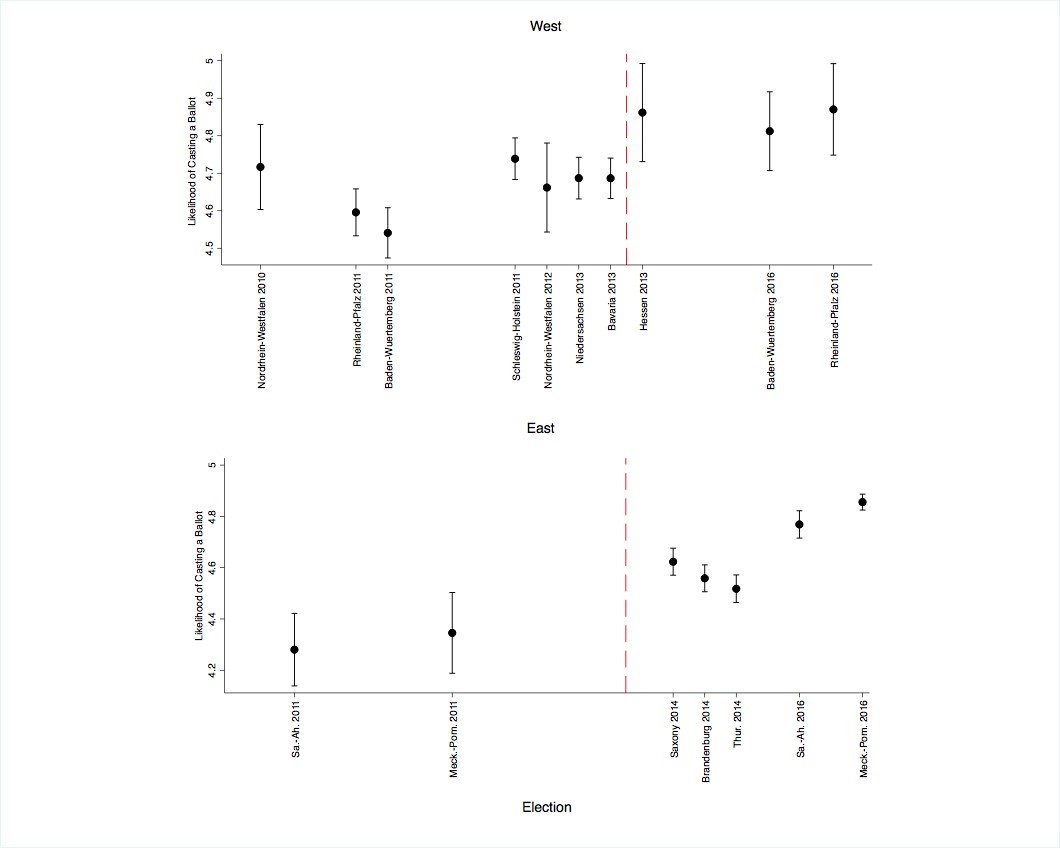

We are particularly interested in the effect of the AfD on individuals who consider themselves ‘right-wing’. Turnout among right-wing individuals was significantly higher in regions where the AfD were on the ballot in regional elections. As shown in the figure below, right-wing voters have been much more likely to vote since the emergence of the AfD in 2013 which offered them a political choice that reflected many of their own preferences. This finding confirms our impression from the exit polls that the success of the AfD was not only due to persuasion – winning over disgruntled voters from established parties who were unhappy with Angela Merkel’s refugee policy – but also due to the mobilisation of individuals who had previously not voted in elections.

Figure 2: Average likelihood of casting a ballot for right-wing voters in different regional elections

Note: Linear prediction with 95% confidence intervals. The dashed line indicates the entrance of the AfD into the party system. Elections for the city states of Bremen, Berlin and Hamburg are not shown.

The electoral success of the AfD can thus be seen in part as the result of mobilising individuals who have previously been disaffected by a lack of a political “voice” in the party system. At the same time, centrist and left-wing voters were also more likely to cast a ballot due to the polarisation of the party system brought about by the emergence of a new party on the far right. It remains to be seen whether the rise of the AfD will lead to a long-term shift to the right in German politics.

In general, AfD voters are less attached to the party and vote for it less out of conviction than voters for the other parties. Moreover, the public departure of party leader Frauke Petry at a press conference on the day after the election shows the depth of internal divisions in the party which covers a spectrum from national-conservative to extreme right. Nevertheless, the success of the AfD represents a significant moment in Germany’s post-war electoral history that may well be the beginning of greater polarisation of German party politics.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

About the authors

Julian M Hoerner – LSE

Julian M Hoerner – LSE

Julian M Hoerner is a Fellow in European Union politics at the LSE European Institute.

–

Sara Hobolt – LSE

Sara Hobolt – LSE

Sara Hobolt is Sutherland Chair in European Institutions at the LSE European Institute.

It should be noted that Germany’s party proportional voting system is one big reason for the AfDs success in this election. Under a British (or Canadian) First Past the Post system, AfD would have only three seats in the Bundestag i.e. the number of “ridings” they won. Germany’s proportional system awarded them 91 more from the AfD list.

This is true, although I also think it has to be said the German system is probably fairer in this respect. I am not a supporter of UKIP, but I did think there were some problems in the 2015 UK election when a party can get over 12% of the vote and only 1 seat.