The EU’s institutional architecture is often regarded as being too complex for citizens to properly engage with, and both Jean-Claude Juncker and Emmanuel Macron have recently proposed some form of simplification such as merging the President of the European Commission with the President of the European Council, or reducing the size of the European Commission. Dimiter Toshkov argues that while the EU is extraordinarily complex, efforts to simplify it are likely to come at the cost of either its inclusiveness or effectiveness.

The EU’s institutional architecture is often regarded as being too complex for citizens to properly engage with, and both Jean-Claude Juncker and Emmanuel Macron have recently proposed some form of simplification such as merging the President of the European Commission with the President of the European Council, or reducing the size of the European Commission. Dimiter Toshkov argues that while the EU is extraordinarily complex, efforts to simplify it are likely to come at the cost of either its inclusiveness or effectiveness.

Credit: © European Union 2017 – European Parliament (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In his 2017 State of the Union address, Jean-Claude Juncker called for a merging of the position of the President of the European Commission – the position he currently occupies – with that of the President of the European Council. This proposal for simplifying the institutional structure of the EU was quickly picked up by the international media, but was almost instantly dismissed as unrealistic by several Prime Ministers of EU member states.

Yet, soon after Juncker’s address, simplifying the EU was put on the agenda by the French President as well. In his widely publicised speech delivered at the Sorbonne on 26 September, Emmanuel Macron declared: ‘The 28 of us need a simpler, more transparent, less bureaucratic Europe’ and made several concrete proposals, for example reducing the number of Commissioners.

There is no doubt that the EU is extraordinarily complex. Its institutional architecture, its decision-making procedures, and its regulatory policies are intricate, tangled and misunderstood. Even leaving the EU is rather complex, as the British are currently finding out. But simplifying the EU can only come at a significant price, and this price might not be worth paying.

The EU is so complex because it needs to be effective and inclusive at the same time. It is easy to design a system that is simple and effective, but not inclusive to the interests of all its constituent parts. And it is easy to design a system that is simple and inclusive, but does not deliver much. Institutions and procedures that are both inclusive and effective need a high level of complexity to find the necessary compromises and opportunities to move forward. Ultimately, inclusiveness and effectiveness might be more important than the efficiency and clarity that simplification can bring.

Why is the European Union so complex?

The institutional setup of the European Union is so complex for three main, and related, reasons: historical legacies, the need for compromise, and flexibility. The European institutions were born out of the need to foster economic and political cooperation between sovereign nation-states. To make cooperation possible, compromises had to be made.

The multiple seats of the EP, the requirements for supermajorities to pass legislation, and the rotating presidency of the Council of the EU provide examples of the cumbersome accommodations made. Once agreed upon, these compromises were enshrined in the founding treaties of the EU, making them extremely difficult to change. Eventually, the member states made new arrangements to remedy some of the most evident inefficiencies of the original institutions. However, this only led to even more complexity. Overlapping, multi-layered, multi-level institutions might be slow and cumbersome, but they are well-suited to accomplish what the EU needs most: finding potential areas for further cooperation, patches of common ground on which to build joint policies and actions.

Historical legacies and the need for compromise go a long way toward explaining the institutional complexity of the EU. The necessary compromises result in discretion and flexibility that, in their turn, lead to high regulatory complexity. To accommodate all member states, EU legislation typically allows for numerous exceptions, exemptions, derogations, transitional periods, and other forms of discretion left to the member states.

Flexibility increases complexity in yet another, more consequential way. Flexible forms of integration allow some states to proceed with further integration without having to wait for the agreement of the rest of the EU’s members. This complicates tremendously the institutional landscape of international cooperation in Europe. At the same time, flexible integration has allowed for European cooperation to progress, even if in a messy and piecemeal fashion. The choice has rarely been between simple and messy integration, but rather between messy integration and no integration at all.

Why simplification is difficult to achieve

Any significant simplification of the current institutional setup of the EU would require a change of the EU treaties, which is itself an extremely complex procedure with a highly uncertain outcome. All member states must ratify new treaties or significant amendments to the current ones in force. In some countries, this might require holding a referendum and the consent of national legislatures.

This would be extremely difficult, if not outright impossible, in the current political environment in Europe. Proposals for treaty change would be used by Eurosceptic parties to incite and mobilise popular opposition towards the EU, regardless of the proposed treaty amendments. Even formally pro-EU political parties are unenthusiastic about raising the political salience of European integration that inevitably comes with treaty reform, given internal party divisions on the issue and considerably Eurosceptic electorates. (Macron’s openly pro-European speech was a rare and welcome exception.)

As a reminder, the most ambitious effort to simplify the EU to date, the proposal for a European Constitution, failed rather miserably. The proposal was drafted over a period of three years, signed by all heads of state on 29 October 2004, and then defeated by referendums in France and The Netherlands in 2005. Among its other innovations, the European Constitution would have radically shortened the existing EU treaties, replacing them with a much more concise document. It would have further simplified the decision-making and law enforcement procedures, and clarified the symbolic identity of the EU. For better or worse, the European Constitution never came to be, although it is unknown to what extent the proposed simplifications had anything to do with its demise.

However, the political lesson of this episode has been clear – EU treaty reform is politically toxic. Opening up the treaties gives new life to old quarrels between the member states about issues such as relative voting power. Renegotiations give opposition parties an opportunity to bash governments for not defending “national interests” enough. Attempts at reform also provide citizens with a rare opportunity to punish runaway political elites and faceless Brussels bureaucrats by rejecting the result of their negotiations.

Proposals for streamlining the EU’s procedures and institutions, decreasing the powers of nation states at the expense of supra-national institutions, and changing the relative balance of power between the nation-states are precisely the types of reforms that are most likely to invite opposition and resentment in the member states, both from the people and from parties playing on populist and nationalist sentiments.

In sum, there are good reasons why the EU is complex – it is what has allowed it to survive as an inclusive and effective organisation, and simplification via treaty reforms is unlikely to succeed in making it any simpler. But, still, there is one thing that the EU and its member states can, and should, do: ensure that all European citizens have a basic understanding of how the EU works.

The importance of understanding the EU

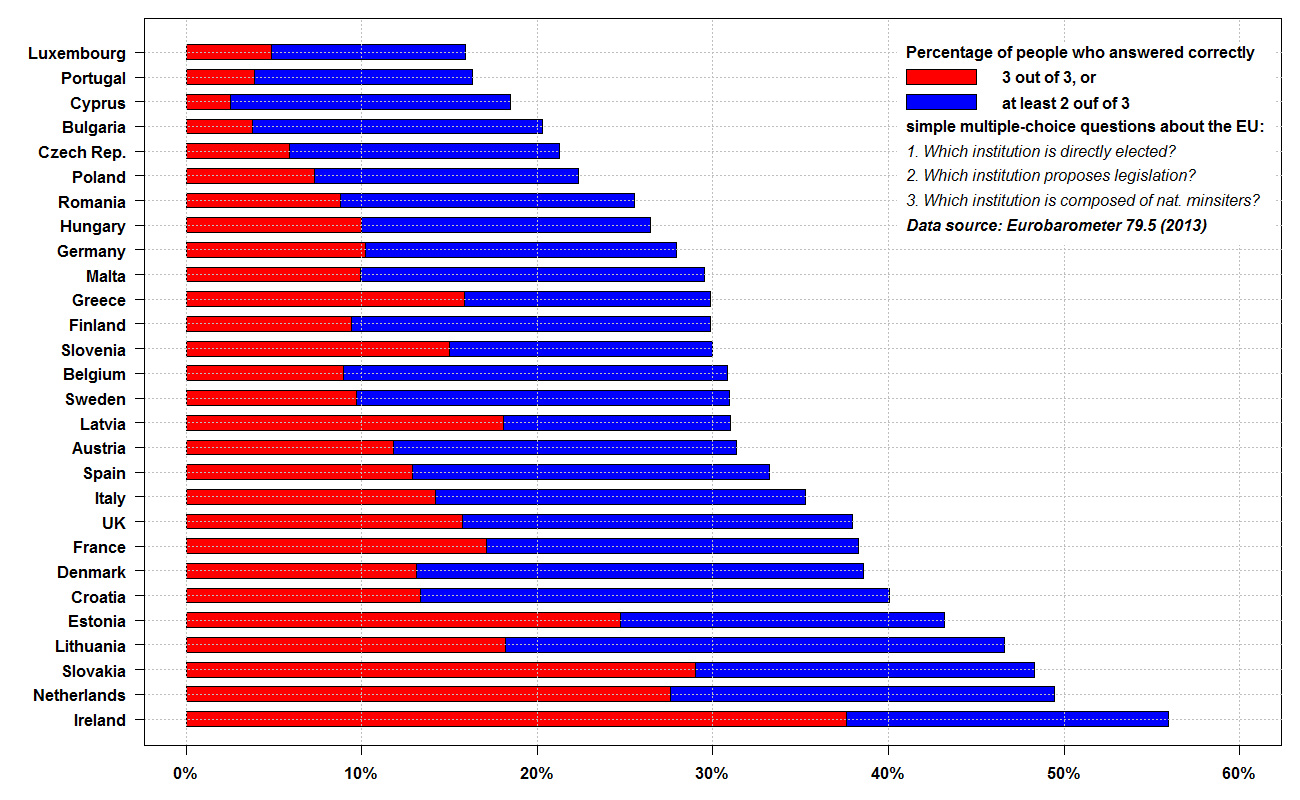

Complexity makes the EU hard to understand, appreciate and trust. But some elementary education can go a long way towards clarifying the fundamental principles of EU decision making, so that citizens understand how European policies are made, and why. Currently, EU citizens know shockingly little about how the EU works. The figure below shows that, as of 2013, in all EU member states bar one, a majority of people could not answer correctly more than one out of three simple questions about the EU’s institutions.

This is especially problematic for a relatively young polity in the making, such as the EU. We know that objective and subjective lack of knowledge about the EU are some of the factors contributing to a relative lack of trust in the EU institutions.

Figure: Public knowledge about EU institutions

Note: The blue bars show the percentage of people in each EU member state that answered at least two out of three simple multiple-choice questions about the EU correctly (the red bars show the percentage of people who answered all three questions correctly).

Approximately 47 percent of the citizens who consider themselves knowledgeable about how the EU works tend to trust it, while only 27 percent of those who do not consider themselves knowledgeable about the EU do. Similarly, while 44 percent of citizens who correctly answer all three simple factual questions about the EU tend to trust it, only 20 percent of those who answer all questions incorrectly do, according to data from the 2013 Eurobarometer survey.

The strong association between knowledge and trust is possibly confounded to some extent by levels of general education and socio-economic status, and the causal links between these two phenomena likely work in both directions (i.e. people who do not trust the EU are also less likely to learn anything about it). But the association remains strongly suggestive of the positive impact of subjective and objective knowledge about the EU on trust in it.

All EU citizens, and young Europeans in particular, should have the opportunity to learn more about the EU and European integration. At the moment, most high-school students across the EU finish secondary education without exposure to any information about the EU. It is hard to expect that people would understand, trust, and support the EU if they have received no reliable information on it during their formative years in school. The EU is complex, and simplifying it may be difficult, but this does not mean that its basic institutions and procedures are beyond the comprehension of its citizens.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article draws on the author’s recent report for the Atlantic Council. The article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Dimiter Toshkov – Leiden University

Dimiter Toshkov – Leiden University

Dimiter Toshkov is Associate Professor at the Institute of Public Administration, Faculty of Governance and Global Affairs, Leiden University, The Netherlands. He is on Twitter twitter: @DToshkov