The last state to join the European Union was Croatia in 2013, but when can current candidate states expect to secure their accession to the EU? Tina Freyburg and Tobias Böhmelt present results from a new study of the capacity of candidate states to meet accession criteria. They find that only one of the current candidate states (Macedonia) would be projected to meet the criteria by 2023, with Serbia and Turkey likely to succeed by the mid-2030s, and Albania and Bosnia-Herzegovina unlikely to meet the criteria before 2050.

The last state to join the European Union was Croatia in 2013, but when can current candidate states expect to secure their accession to the EU? Tina Freyburg and Tobias Böhmelt present results from a new study of the capacity of candidate states to meet accession criteria. They find that only one of the current candidate states (Macedonia) would be projected to meet the criteria by 2023, with Serbia and Turkey likely to succeed by the mid-2030s, and Albania and Bosnia-Herzegovina unlikely to meet the criteria before 2050.

Federica Mogherini and Serbia’s Aleksandar Vučić at the 2015 Western Balkans Summit, Credit: EEAS (CC BY-NC 2.0)

After several years of being largely absent from the agenda, the Western Balkans are back in focus – mainly due to the refugee crisis but also in response to Russia’s renewed interest in this part of the world. While Russia confidently announces that it can offer an alternative to Euro-Atlantic integration, the European Union reaffirmed earlier this year in Trieste its commitment to enlargement for the Western Balkans “Six” with a view to helping them fulfil the economic and political requirements for accession to the EU. In particular, the German government reinforced its “Berlin Process” initiative by suggesting a “Berlin Process plus” agenda, also called a “mini Marshall Plan,” in order to give the region’s economies a lift – and, in a way, to also compensate for the long wait for EU membership.

Yet, how likely is it that a candidate state will be ready to join the EU within the next 10, 15 or more years? In a recent study, we looked at the candidates’ capacity to comply with the massive EU acquis communautaire, which constitutes the primary condition for proceeding with the negotiations and ultimately securing the accession of a new EU state.

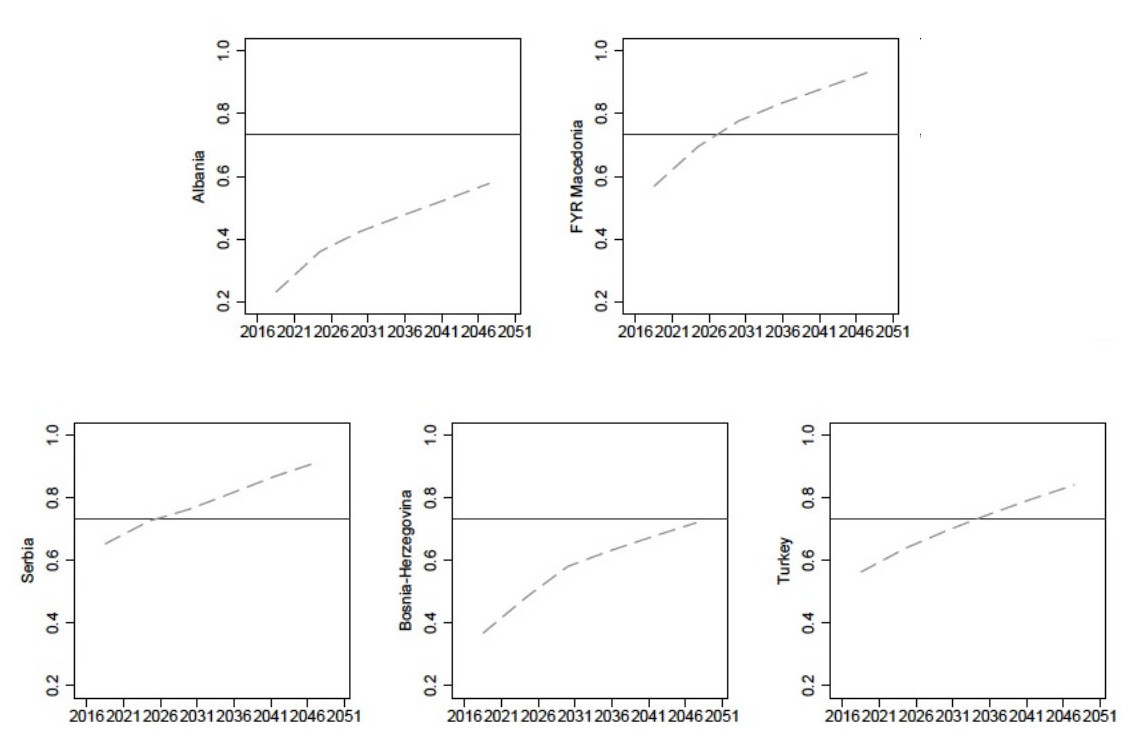

Using the 2004 accession round as a benchmark, our results show that only one country of the current and potential candidates is likely to sufficiently comply with the accession criteria by 2023, FYR Macedonia. While Serbia and Turkey are likely to succeed in the mid-2030s, Albania and Bosnia-Herzegovina might have difficulties in meeting the set standards even by 2050. Montenegro, despite being considered as one of the Western Balkans states with the best chance to accede, was omitted from the analysis due to a lack of data.

These figures are based on predictions of a state’s ability to comply with EU laws using proxies for adjustment costs and administrative capacities. Specifically, we use indicators that accurately predict compliance behaviour of previous, current and potential candidate states between 1998 and 2016 and for which we have projections up to 2050. The figure below shows the predicted level of compliance for each state in the study.

Figure: Candidates’ predicted levels of compliance with the EU acquis (click to enlarge)

Note: The horizontal solid lines represent the threshold for a sufficient level of compliance based on the 2004 round of enlargement. The dashed lines show the forecasted compliance levels for 2017-2050.

What is certain is that states in the Western Balkans hope to join the EU one day. This is the expectation held by any applicant facing the demanding process of bringing all its national laws, regulatory frameworks and administrative practices in line with the Union’s standards and laws. And the future of enlargement policy is, obviously, anything but determined.

Despite showing a certain path dependency caused by the rigidity of its rules, the process of enlargement is open to various influences that might change the timing of the Western Balkans candidates’ progress, if not their accession. Signs that perhaps indicate a quickening of the process might come in the shape of political changes, like the recent transfer of power to a more pro-European government in Macedonia. Conversely, the worsening state of Turkey’s democratic institutions might cause the enlargement process to freeze for several years.

Earlier work has paid little attention to predicting and forecasting states’ performance in implementing EU law. As a consequence, policymakers lack guidance for assessing the success of EU enlargement policy and for making an informed statement on the likely timing of future accession.

Knowing in advance which of the (potential) current candidate states are less likely to comply with EU regulations over the course of accession is essential for the EU’s monitoring and enforcement schemes, as well as for facilitating an informed public debate about future enlargement. Forecasting a candidate state’s ability to comply with the EU’s accession criteria can help to understand enlargement as a lengthy process. This insight might encourage the formulation of measures aimed at enhancing a candidate state’s capabilities.

Note, however, that our figures might still paint too optimistic a picture since we cannot account for random events or states’ unwillingness to comply in the future. The actual future compliance levels of the individual candidate states could well be even weaker than those predicted in our study.

In any case, our results underline the fact that claims, such as those made by the Vote Leave campaign in the UK’s EU referendum, that most of the candidates will join by 2020 are likely to be very much mistaken. To the contrary, more efforts are necessary if the EU wants to see “a practical and tangible advancement of all our six partners from the Western Balkans, an advance that will make their road towards the EU irrevocable”, as Federica Mogherini, the EU’s High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, emphasised at the recent Bled Strategic Forum.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. For a longer discussion of this topic, see the authors’ recent article in the Journal of European Public Policy.

_________________________________

Tina Freyburg – University of St Gallen

Tina Freyburg – University of St Gallen

Tina Freyburg is a Professor of Comparative Politics in the School of Economics and Political Science at the University of St Gallen, Switzerland.

–

Tobias Böhmelt – University of Essex

Tobias Böhmelt – University of Essex

Tobias Böhmelt is a Professor in the Department of Government at the University of Essex.

Do you know what’s going to happen to these countries if the EU doesn’t take them under their wing soon?

Russia will.

What a pity, shame on the “civilised” West. Back to the pre 90’s.

Disgusting.

Ed: I see your point but over rapid enlargement in 2004 is still causing problems for the EU. Although I am a firm supporter of the EU, I don’t beleive the 2004 were ready for membership. A change in EU law, at the very least, is required to enable the EU to directly enforce the regulations and the rule of law. Otherwise thd EU will become just a lose trade block and talking shop. Promoting the highest standards of the rule of law and lowest corruption must be a number one priority for the EU.

wooh

quite a dramatization

Russia would love to have satellite- and client-states, especially whenever they can be used as pawns to disrupt/influence the stability of bigger organisation.

that said, the EU never said that enlargement was off for the Balkan countries. though it’s certainly true for Caucasians and Ukrainians. it’ll only takes longer for some that initially thought so.

Russia is anyway still trying to play its “sore loser, disruptor in chief” irrespective of whether a country is part of the EU (look at Hungary, Czech Republic, Greece, Bulgaria for the most egregious cases of corruption). Macedonia, Serbia, Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia are also cases of active destabilisation.

… and so it has been for years, nothing much new.

what’s limiting Russia is quite simply the availability of hard currency and political stability at home.

Ed, Russia has already taken over.

Serbia has always been in their camp, they tried with Montenegro, and as of last year, they have Bosnia as well (via Serbian and Croatian proxies).

In fact, Russia has even made inroads into Croatia, an EU and NATO member. Google Agrokor and Sberbank for the full lowdown.

If these countries don’t get access to the Eu soon then EU will pay the price

People of western balcans need jobs not and free to find job not just free movement

Why is Kosovo not being considered at all?

Ukraine is not even considered and lots of people have been lured by false promises.

The text and the graphics don’t coincide. The graphics suggest that North Macedonia will reach a sufficient level of compliance by 2027, not 2023. It also suggests that Serbia would reach a sufficiently level of compliance by 2025-2028 (so potential even before North Macedonia), not in the “2030s”. Albania’s trendline, if extended, suggests it would not be ready until around 2065, while Bosnia would be reach a sufficient level of compliance around 2048.

It doesn’t seem like Georgia, Moldova, Ukraine or Kosovo were considered, but given Albania’s trendline, I would not expect any of those four to be ready before the 2060s either (Georgia may be ready by the 2040s maybe). A lot can happen by that time which means some of those countries may decide to no longer pursue membership as Norway, Iceland and Sweden had done.