A second round run-off will be held in the Czech presidential election on 26-27 January, with incumbent president Miloš Zeman facing a challenge from former head of the Czech Academy of Sciences Jiří Drahoš. Lenka Dražanová highlights the role that immigration has played in the campaign, despite the Czech Republic experiencing relatively low levels of immigration in comparison to other European countries.

A second round run-off will be held in the Czech presidential election on 26-27 January, with incumbent president Miloš Zeman facing a challenge from former head of the Czech Academy of Sciences Jiří Drahoš. Lenka Dražanová highlights the role that immigration has played in the campaign, despite the Czech Republic experiencing relatively low levels of immigration in comparison to other European countries.

Miloš Zeman, Credit: United Nations Photo (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The Czech Republic has experienced relatively low levels of immigration, but negative attitudes toward the issue have powerfully shaped the country’s upcoming presidential election. This is because the country’s history, its relatively limited experience of immigration, and the strong anti-immigration and anti-Muslim signals sent by political leaders have had powerful effects on public attitudes.

The second round run-off on 26-27 January will pit current president Miloš Zeman against the former head of the Czech Academy of Sciences, Jiří Drahoš. Zeman edged the first round with 38.6% of votes with a campaign that was Eurosceptic, pro-Russian and anti-immigration. He railed against Muslim immigration, which he called an “organised invasion” of Europe and criticised EU refugee policies.

Zeman will face a formidable challenge in the second round of voting from the pro-western Drahoš, who polled 26.6% in the first round. Drahoš unequivocally supports the EU and NATO membership and has criticised Russian meddling in European elections. But there’s less between them on immigration. Drahoš rejects EU plans for the relocation of asylum applicants because, as he puts it: “we must defend our culture”. He has argued for tough border controls and increased development aid to migrant-sending countries in a bid to stem future flows.

Ethnic belonging is an important part of the Czech identity. For many Czechs, immigration, with its implicit ethnic and cultural blending, is perceived as endangering the Czech nation and people. Like other Central Europeans, Czechs have experience of moving borders and minorities becoming majorities. They see ethnicity as an important marker of identity. Since its formation from the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1918, ethnic identity played an important role within Czechoslovakia given the absence of a Czechoslovak identity – people were always either Czech or Slovak – and long periods of foreign occupation.

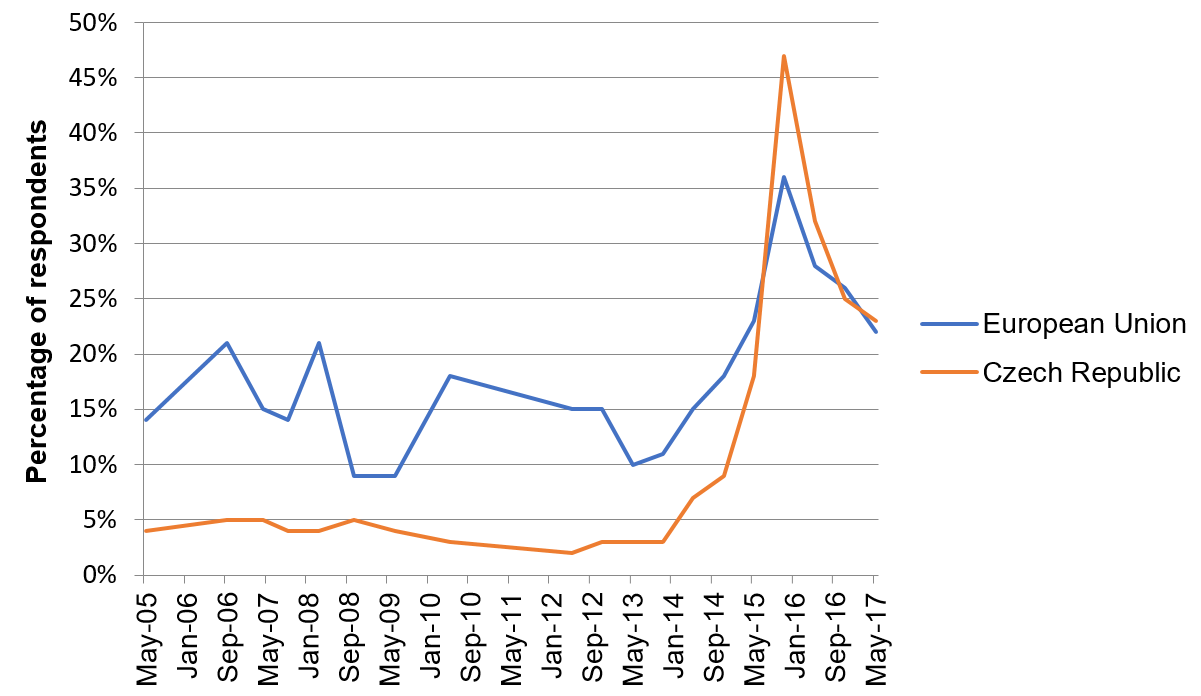

By the end of 2016, there were 288,247 non-EU immigrants in the Czech Republic, around 3 percent of the total population. Ukraine and Vietnam were the main non-EU origin countries. Numbers of asylum seekers and refugees are very low compared to other EU member states. In 2016, around 1,400 applications were made in the Czech Republic out of an EU-wide total of 1.2 million. Until January 2014, immigration barely registered as a concern, but less than a year later, as Figure 1 shows, 47% of Czechs saw immigration as one of the two most important issues facing the country. Salience has dipped slightly from its 2015 and 2016 peaks, but Figure 2 shows continued high concern about immigration in the run-up to the presidential election.

Figure 1: Percentage of respondents selecting immigration as one of the two most important issues facing the Czech Republic (2005-2017)

Note: The question was: “What do you think are the two most important issues facing your country at the moment?” Source: Eurobarometer

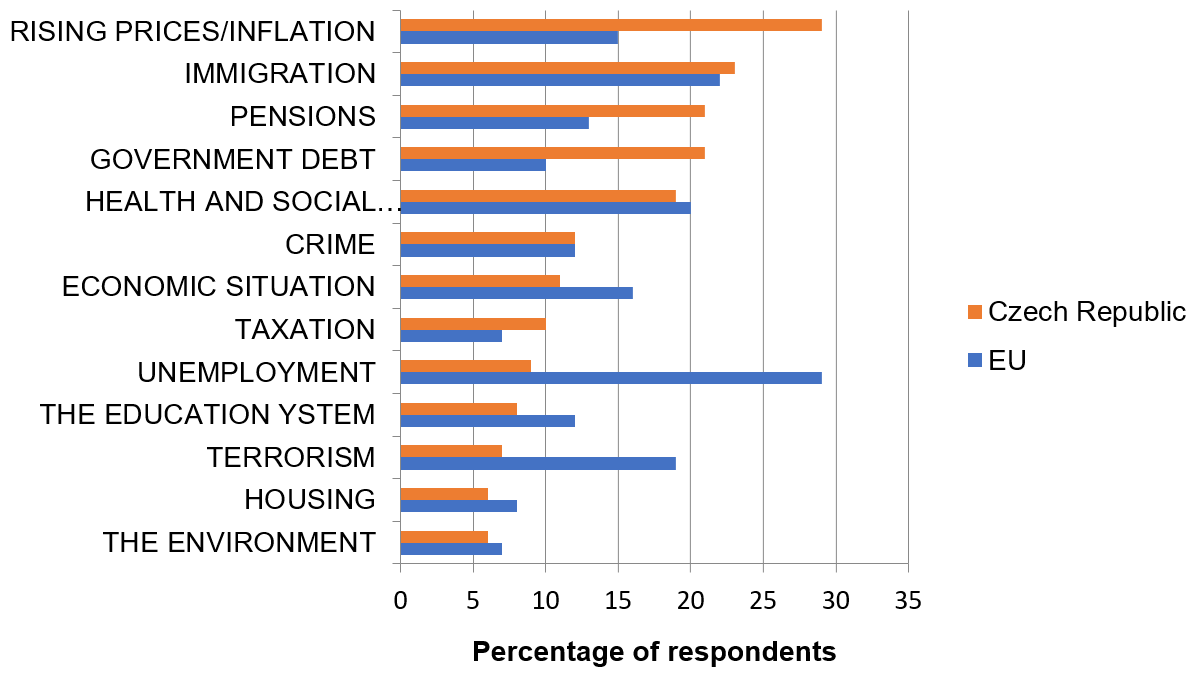

Figure 2: The two most important issues facing the Czech Republic (May 2017)

Note: The question was: “What do you think are the two most important issues facing Czech Republic at the moment?” Source: Eurobarometer 87, 2017

Relatively low numbers of immigrants and limited possibilities for direct contact mean that many Czechs rely on cues or signals from politicians. Incumbent president Zeman has been resolute in his opposition to EU plans for the relocation of Muslim asylum applicants from war torn Syria. Former Interior Minister Milan Chovanec of the Social-Democratic party (ČSSD) has posed with a gun that he claimed was needed to defend himself from Muslim terrorists. Meanwhile earlier this month, Senator Jaroslav Doubrava claimed that: “there are buses of illegal migrants coming to Prague from Germany”.

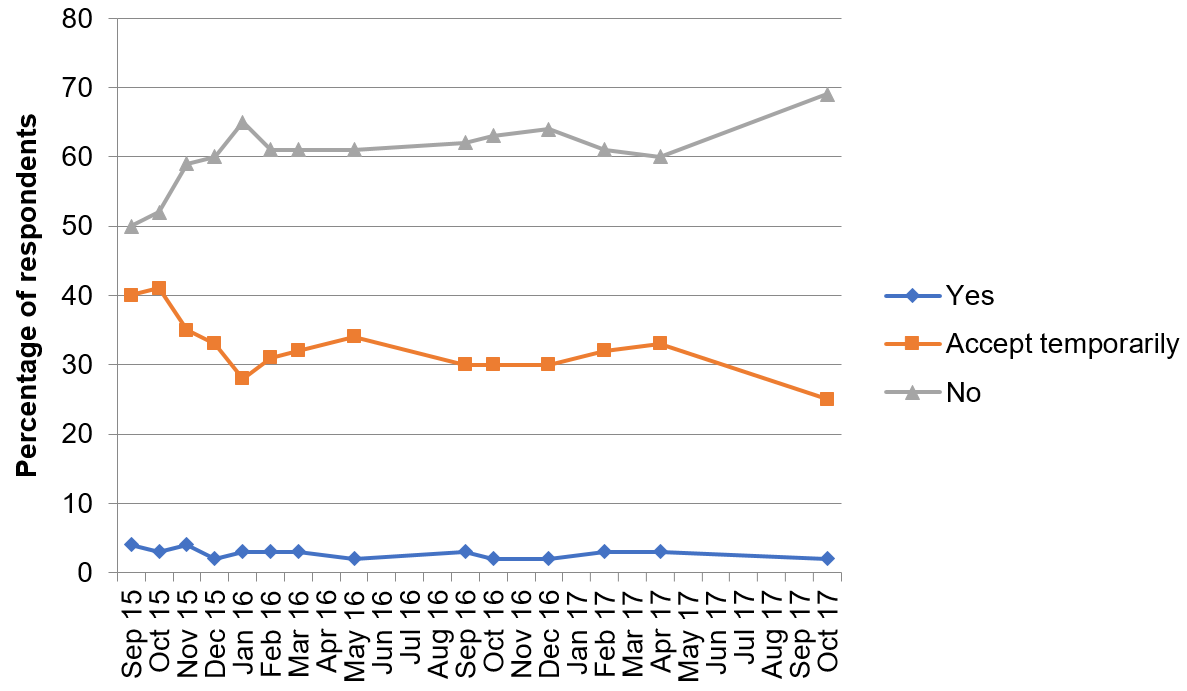

Figure 3 shows that 69 percent of respondents agree that the Czech Republic should not accept refugees from war-torn countries, with 25% agreeing to accept them on the condition that they return to their home countries. Only 2% agree that refugees should remain. Attitudes differ according to countries of origin with significant opposition towards the acceptance of refugees from the Middle-East.

Figure 3: Should the Czech Republic accept refugees from war-torn countries? (Sep 2015 – Oct 2017)

Note: The question was: “In the last year the European Union has faced a higher number of refugees especially due to war conflicts. According to you, should the Czech Republic accept refugees from countries in war?” Source: CVVM

While immigration has been a salient issue across Europe, this concern has been even more marked in the Czech Republic despite there being relatively low levels of immigration. The American psychologist Gordon W. Allport argued that interpersonal contact is one of the most effective ways to reduce prejudice between majority and minority group members. The low numbers of immigrants in the Czech Republic, relative ethnic homogeneity and the country´s 40-years of isolation during the communist era, means that Czechs rely on cues from politicians instead of interpersonal contact.

Zeman has also highlighted the country’s historical experience to claim that immigration could endanger the cultural and ethnic identity of the Czech nation. This helps to explain why Czech attitudes towards migrants and refugees, particularly from Muslim countries in the Middle-East, have been so hostile despite the relatively small numbers that actually get to the country.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Lenka Dražanová – European University Institute

Lenka Dražanová – European University Institute

Lenka Dražanová is a Research Associate at the Migration Policy Centre (MPC) in the European University Institute.