The results of the German Social Democrats’ (SPD) membership referendum on Germany’s new grand coalition are expected on 4 March. Ragnar Weilandt argues that opponents of the grand coalition should think twice before vetoing it. SPD members fear that four more years under chancellor Merkel might destroy their party. But the alternatives may be worse for Germany, Europe and the SPD itself.

The results of the German Social Democrats’ (SPD) membership referendum on Germany’s new grand coalition are expected on 4 March. Ragnar Weilandt argues that opponents of the grand coalition should think twice before vetoing it. SPD members fear that four more years under chancellor Merkel might destroy their party. But the alternatives may be worse for Germany, Europe and the SPD itself.

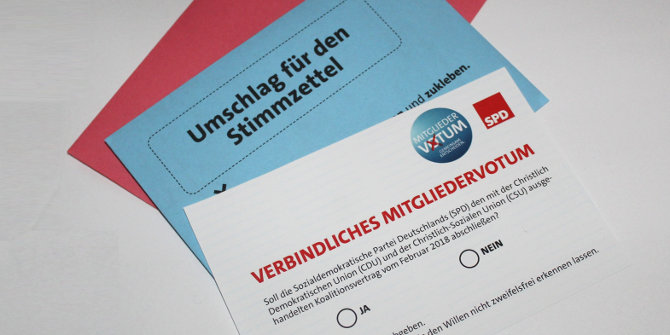

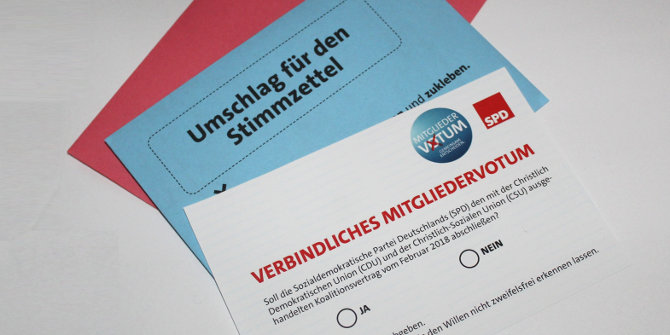

Credit: Mummert & Ibold Internetdienste GbR (CC BY 2.0)

The leadership of Germany’s Social Democratic Party (SPD) should have spent the last few weeks celebrating. Securing several key posts in Germany’s next government, including the finance ministry, was more than they could have hoped for after the party’s worst election result in post-war history. Its negotiation team seemed to have played its bad cards well.

But rather than celebrating, the party switched to self-destruction mode. Senior SPD politicians openly attacked party leader Martin Schulz’ decision to become foreign minister as he had previously declared that he would “never enter” a government under Angela Merkel. Former party leader and current foreign minister Sigmar Gabriel lashed out at the SPD’s leadership, hinting at a breach of faith against him. By the time Schulz gave up his ministerial ambitions, the damage was done. And his replacement as party leader has dragged the SPD into yet another crisis. Parts of the party were left fuming over the way the leadership settled on Andrea Nahles, as well as their ultimately unsuccessful attempt to immediately install her as caretaker leader, which would have breached internal procedures.

This in-fighting doesn’t help advocates of the grand coalition or “GroKo” to make their case. But a “yes” vote in the SPD’s membership referendum, the results of which will be announced on 4 March, was far from secure even before the chaos erupted.

A look back at previous votes helps to illustrate how close it may get. During an SPD party convention following the 2013 elections, 87 per cent of delegates voted in favour of negotiating with Merkel’s Christian Democratic Party (CDU). After both parties agreed on a coalition treaty, 76 per cent of party members voted in favour in an internal referendum. Back then, the party base was more sceptical than its delegates. Little suggests that this has changed, and this time only 56 per cent of party delegates supported starting negotiations.

On top of that is the fact that the SPD’s youth wing has managed to get more than 24,000 new members to join the SPD since the turn of the year in a Momentum-style campaign aimed at blocking the grand coalition. Even members in favour are not exactly enthusiastic about yet another four years under chancellor Merkel. Most see another GroKo as a necessary evil rather than something which is genuinely desirable. It won’t be easy to mobilise them to vote.

In contrast to 2013, the internal opposition is not just motivated by policy disagreements, and opposition is not limited to left-leaning members. Many have misgivings about the coalition treaty, but more importantly they fear that another GroKo will destroy their party and further strengthen the political extremes.

The SPD had its worst post-war election result in the 2017 federal elections. Polls have seen it drop further in recent weeks, dropping to only a few points ahead of the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD). To add insult to injury, the GroKo would leave the AfD as the main opposition party, which grants its parliamentarians substantial speaking rights and important committee posts. Many look to Austria, where successive grand coalitions have strengthened the far-right Freedom Party to the extent that it became the king-maker in parliament and almost won the presidency.

Moreover, even before the latest chaos, many SPD members were fed up with their leadership. They are disappointed over its inability to run an appealing campaign at a time when the party’s classic themes revolving around social justice were staging a comeback. And they are stunned by its flip-flopping since the election. Shortly after the exit polls came in, Martin Schulz committed to avoiding a grand coalition. He repeated this commitment after explorative negotiations for a Jamaica coalition between the Greens, Liberals and Conservatives collapsed, only to change his line within days.

The leadership’s ensuing arrogance towards those opposing this U-turn even left GroKo supporters speechless. As a result, many will also see a “no” vote as a chance to get rid of the current leadership and to set in motion a much-desired generational change at the top. That a failure to renew the GroKo might even end Angela Merkel’s political career is an additional incentive.

But while it is understandable that they do not exactly find another grand coalition desirable, opponents within the SPD have to ask themselves what the alternatives are. A minority government would either produce instability and deadlock or a de-facto grand coalition, just without SPD politicians being able to set the agenda from within government. New elections are unlikely to produce a result that allows for constellations other than a Jamaica coalition or a GroKo. In light of the poor show the SPD put up lately, new elections might also further diminish the party. Not least as a recent poll indicates that 57 per cent of the electorate and a whopping 84 per cent of SPD voters want the party’s members to vote in favour of the GroKo.

GroKo opponents should also consider whether they really want to gamble away a genuine chance for Europe. Merkel and Macron may not revolutionise the EU, but German and French governments as pro-European, as similar in their vision on the Union’s future and as sympathetic towards each others’ ideas and concerns do not coincide often. There is momentum for important reforms right now, but it may fade away if Germany doesn’t get a stable government soon.

Most importantly, SPD members need to stop scapegoating the grand coalition and chancellor Merkel for their electoral demise or the rise of the far-right. The Alternative für Deutschland emerged during the last coalition between Merkel’s CDU and the German liberals. Its rise over the past four years can be largely attributed to the refugee crisis. And if the last days and weeks are any indication, then the SPD’s drift towards irrelevance is very much the party’s own doing.

Whether with the minimum wage, pension reforms or marriage equality, the SPD have actually pushed through reforms that were genuinely popular with German voters over the past four years. It has to ask itself why it failed to capitalise on that. And as with other centre-left parties across Europe, it has to define what social democracy means in a world shaped by globalisation and automatisation, and it needs to make clear why its approach to managing these processes is needed. This will take time. But it won’t necessarily be easier in opposition.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Ragnar Weilandt – Université libre de Bruxelles / University of Warwick

Ragnar Weilandt – Université libre de Bruxelles / University of Warwick

Ragnar Weilandt is a doctoral research fellow at the Université libre de Bruxelles and the University of Warwick. He works on European Union politics, with a special focus on the EU’s external relations towards its Southern Mediterranean neighbourhood. He is on twitter @ragnarweilandt