Do populist parties behave differently from other parties when they enter parliament? Presenting evidence from a study of parties in the Netherlands, Simon Otjes and Tom Louwerse illustrate that both left-wing and right-wing populist parties tend to primarily voice opposition rather than offer policy alternatives. The growing representation of populist parties in West European parliaments is therefore likely to lead to an increase in confrontational politics focused on scrutiny rather than policy-making.

Do populist parties behave differently from other parties when they enter parliament? Presenting evidence from a study of parties in the Netherlands, Simon Otjes and Tom Louwerse illustrate that both left-wing and right-wing populist parties tend to primarily voice opposition rather than offer policy alternatives. The growing representation of populist parties in West European parliaments is therefore likely to lead to an increase in confrontational politics focused on scrutiny rather than policy-making.

Populist political parties form an important part of the political landscape of West-European democracies. Recently we have seen a number of populist parties, like the Austrian Freedom Party and the Italian Five Star Movement enter government. These parties have been in parliament for years. Yet, we know surprisingly little about how they operate in parliament. Do they have a preference for particular political tools or strategies? Does their populism feed into their parliamentary behaviour? In a recent study we examined this by looking at the Netherlands.

At the core of our paper is a simple typology of parliamentary opposition activity. There are two ways Members of Parliament (MPs) can operate. First, they can attempt to use the legislative arena to change policy. MPs can initiate new legislation or they can propose to amend the text of that bill. They can also propose parliamentary motions to get the minister to change policies or propose bills. We call this kind of behaviour “Policy-Making Activity”.

Alternatively, they can voice their opposition to the government and its policies. They can do so by asking questions to a minister. Such questions are often an opportunity to draw attention to a policy failure or direct attention to an issue that a minister has ignored. Many parliaments have the option to ask written questions and the option for a limited number of oral questions in parliament. Another way to voice criticism is by voting against government bills. We call all this kind of activity “Scrutiny Activity”.

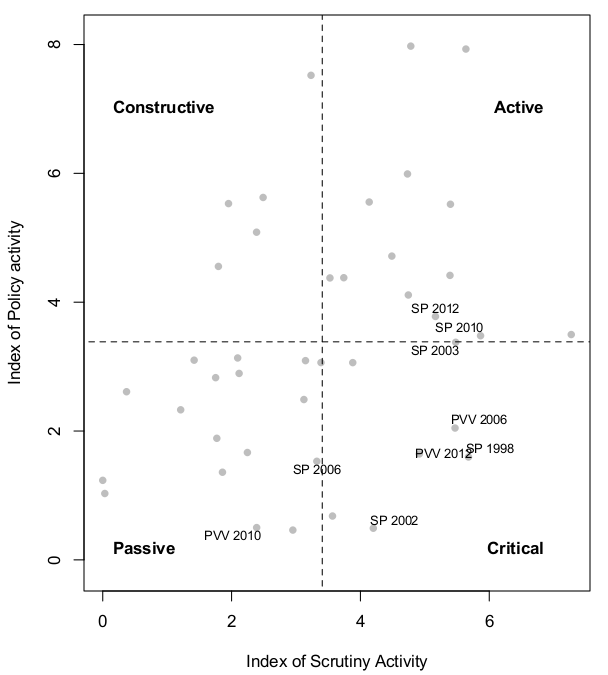

By combining these two dimensions, we arrive at a typology of opposition party activity. Opposition parties can use policy-making tools but neglect scrutiny tools. This kind of party focuses on finding majorities for new policies. We call this kind of behaviour “constructive opposition”. The opposite strategy would be to mainly use scrutiny tools and abstain from policy-making. This kind of party focuses on pointing out what is wrong. We call this kind of behaviour “critical opposition”. Naturally parties can also use both scrutiny and policy-making tools often: that is, offer criticism and alternatives. We call this “active opposition”. Finally, an opposition party can simply do nothing: use neither scrutiny tools nor policy-making tools: this would be the “passive opposition”.

We expect populist parties to be concentrated in the critical quadrant. We follow the consensus in the literature that conceives of populism in terms of two claims: first that the actions of the government should reflect the general will of the people and second that the ruling elite deprives the people of their right to rule. Anti-elitism is an important element in populism for our study. We propose that this factor makes them more likely to prefer scrutiny tools to policy-making tools. If an opposition party wants to influence policy-making it needs to make compromises with the ruling parties. We expect populist parties not to want to engage in this. Instead we propose that populist parties are likely to use scrutiny tools to criticise the government but also to draw attention to issues that the government neglects.

We studied opposition party behaviour in the Dutch parliament to test our expectations. We selected the Netherlands because it has both a left-wing populist party (the Socialist Party) and a number of right-wing populist parties (such as the Freedom Party). By studying the behaviour of both left-wing and right-wing populist parties, we made sure that our results do not reflect the party’s left-right ideology but rather their actual populism.

Figure: Parliamentary behaviour by political parties in the Netherlands

Note: SP refers to the Socialist Party; PVV refers to the Freedom Party. For more information, see the authors’ accompanying study.

The figure above quickly summarises our results. It places all Dutch political parties in the two-by-two figure. The Socialist Party and the Freedom Party are labelled. We can see that in general most populist parties are in the lower right corner. Here we find both the left-wing Socialist Party and the Freedom Party. This conforms to our expectations: populist parties voice opposition rather than offer alternatives. In our detailed statistical analysis, we find that the relationship between populism and the policy-making dimension is stronger than the relationship between populism and the scrutiny dimension.

So what do these results mean for other countries? One should note that the Dutch parliament allows opposition parties to use quite a broad range tools. In other parliaments, the freedom afforded to opposition parties may be more limited. Interestingly, this is likely to focus opposition parties in the lower right corner as most parliaments limit the policy-making power of opposition parties. Therefore, we expect most opposition parties and in particular populist opposition parties in West European parliaments are likely to be critical opposition parties. The growing representation of populist parties in West European parliaments is likely to lead to an increase in confrontational politics focused on scrutiny rather than policy-making.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in Political Studies.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Tweede Kamer

_________________________________

Simon Otjes – Groningen University

Simon Otjes – Groningen University

Simon Otjes is a researcher at the Documentation Centre Dutch Political Parties of Groningen University. His research focuses on parliamentary behaviour, public opinion and political parties. He has previously published on in journals such as the American Journal of Political Science and European Journal of Political Research and Party Politics.

Tom Louwerse – Leiden University

Tom Louwerse – Leiden University

Tom Louwerse is Assistant Professor in Political Science at the Department of Political Science, Leiden University, the Netherlands. His research interests include political representation, parliamentary politics, voting advice applications and political parties. He has published in various international journals, including Acta Politica, Electoral Studies, The Journal of Legislative Studies, Parliamentary Affairs, Party Politics, Political Science Research and Methods, Political Studies, and West European Politics.