Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan secured victory in legislative and presidential elections on 24 June. The vote ensured that Erdogan can now govern the country using new executive powers which were approved in a referendum in 2017. Sevinç Bermek and Ledün Çevik write that although there were no radical shifts in support from the last legislative elections in 2015, it is difficult to predict where Turkish politics will go from here given the changes that have been made to the country’s political system.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan secured victory in legislative and presidential elections on 24 June. The vote ensured that Erdogan can now govern the country using new executive powers which were approved in a referendum in 2017. Sevinç Bermek and Ledün Çevik write that although there were no radical shifts in support from the last legislative elections in 2015, it is difficult to predict where Turkish politics will go from here given the changes that have been made to the country’s political system.

Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Credit: NATO (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

On 24 June, Turkey held both legislative and presidential elections. Though the elections were supposed to take place next year, a snap election was called after Erdogan’s meeting with his ultranationalist ally Devlet Bahceli, who is the leader of the Milliyetci Hareket Partisi (Nationalist Movement Party – MHP).

It is important to remember that Turkey had held a referendum for a shift from parliamentary democracy toward an executive presidency in April 2017. The new system was accepted by a narrow margin (51.4 per cent voting in favour). Since the failed coup in July 2016, the country has been de facto ruled by the presidential system due to the state of emergency status. This has provided excessive power to Erdogan to govern the country with decrees and has supressed legislative authority. In line with this already unusual political background, the 2018 elections legitimised this ruling system.

The presidential elections

For the presidential elections, there were six candidates; the main rivalry occurred among Erdogan, Muharrem İnce, Meral Aksener, and Selahattin Demirtas. Erdogan’s Adalet ve Kalkinma Partisi (Justice and Development Party – AKP) established a ‘People’s Alliance’ with Bahceli’s MHP for both the presidential and legislative elections and aimed to target conservative-nationalist constituencies.

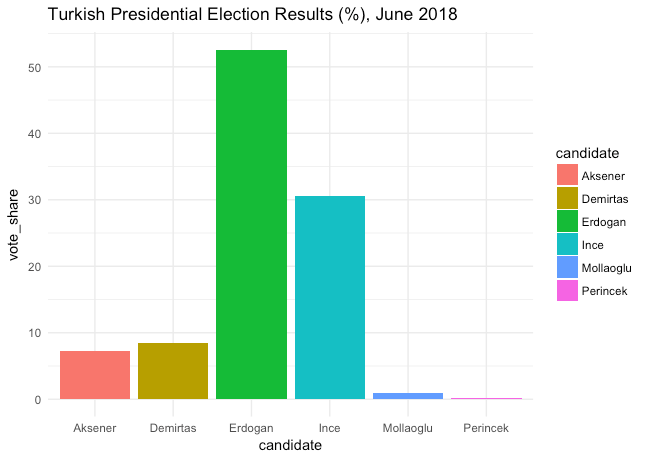

During the electoral campaign, Erdogan promised reinforcement of the economy (especially with regard to interest rates and inflation) as well as further integration into the global economic market. Erdogan received 52 per cent of the votes and was thereby re-elected for the second time as president (as shown in Figure 1). The results illustrate the conservative, nationalist and intermediary strata’s allegiance to Erdogan – albeit a weaker allegiance than a decade ago – and their support for his proposals on political stability. Regarding political stability, the public’s concerns over national security and the rise of terrorism played a strong role in Erdogan’s re-election as president. The results also highlighted approval for the economic policies pursued by his administration over the last couple of years which have fuelled consumption (and borrowing) led-growth that primarily benefited his core constituents.

Figure 1: Results of the June 2018 Turkish presidential election

Note: Figures compiled by Aslı Ünan.

In addition, his alliance with the ultranationalist bloc significantly helped his campaign for the presidency since the MHP did not nominate a candidate from its cadres and instead supported Erdogan’s candidacy for its second tenure. Among the candidates, Erdogan’s main challenger was Ince who got 30.6 per cent of the votes. Even though Ince lost his chance for the presidency, he managed to unite the oppositional bloc (including Kurdish voters) along the axes of secularism, parliamentary democracy and justice. His campaign attracted millions of people, especially in three metropolitan cities due to his inclusive approach. The lack of a sound economic reform package and the fact he did not go beyond his critique of Erdogan damaged his chances. Nevertheless, due to his increasing popularity, he may play a crucial role in the internal party politics of the Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi (Republican People’s Party – CHP) in the near future.

Demirtas, of the Halklarin Demokratik Partisi (People’s Democratic Party – HDP), ran his campaign from prison following his arrest on terrorism charges. Despite the obstacles this posed for conducting a political campaign, he still received 8.4 per cent of the vote and became the third most popular candidate. Lastly, Aksener, who got 7.3 per cent of the vote, has become a critical actor due to his ability to secure both nationalist and secular votes.

Legislative elections

Overall, the presidential elections highlighted that the Turkish electorate has continued to prioritise ‘stability under strong leadership’, but the legislative election results sent a different set of signals. Similar to the presidential elections, the parties established alliances for the legislative contest: the AKP and MHP’s People’s Alliance; while the CHP, the İyi Party (Good Party – IP) and the Saadet Partisi (Felicity Party – SP) established the Nation’s Alliance (Millet Ittifaki). The left-leaning pro-Kurdish HDP did not join either of these alliances.

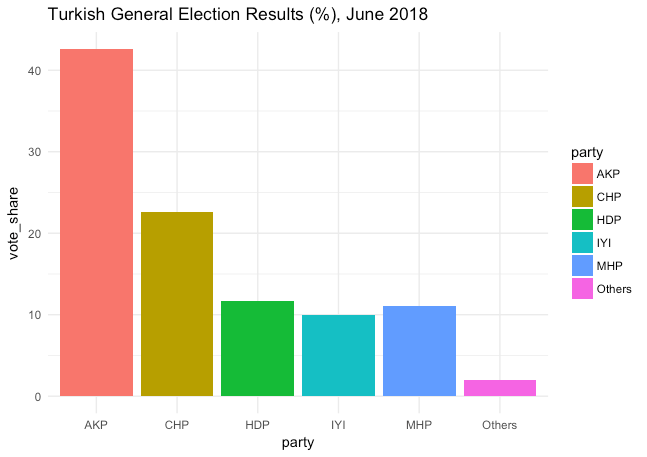

The legislative elections highlighted that Turkish voters remain in two core blocs, and there has been a minor shift of votes from one bloc to the other. The Turkish electoral system requires a party to obtain at least 10 per cent of the national vote to have seats in parliament. Much as was the case in the presidential election, Erdogan’s victory was secured via the ultranationalist vote, but the MHP also managed to pass the electoral threshold (11.1 per cent, 49 seats) by securing the nationalist and Islamist votes of the AKP. In the meantime, the AKP remained the leading party with 42.5 per cent (295 seats).

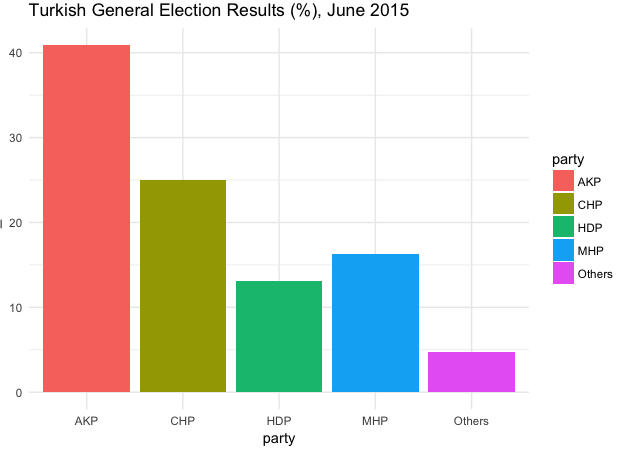

Similar to the vote trading that took place among the conservative-nationalist bloc, the CHP’s urban and left-oriented constituency voted for the HDP to help them pass the threshold (with 11.7 per cent, 67 seats), something that had previously occurred in the two legislative elections held in 2015. The CHP remained the main opposition party with 22.6 per cent (146 seats). Figure 2 shows how the electoral picture looked after the legislative election in June 2015, while Figure 3 shows how this picture has changed (or rather, not changed) following the 2018 legislative election.

Figure 2: Results of the June 2015 Turkish legislative election

Source: Supreme Electoral Council of Turkey; compiled by Aslı Ünan.

Figure 3: Results of the 2018 Turkish legislative election

Source: Supreme Electoral Council of Turkey; compiled by Aslı Ünan.

Meanwhile, the IP, which was established as a centre-right alternative for the conservative Turkish electorate, managed to secure 65 seats by capturing the support of CHP, MHP and AKP voters. Overall, in terms of the political cleavages that exist in Turkish politics, there were no significant transfers of votes across the two blocs and the electorate remains highly polarised. As socio-economic, ethnic and ideological cleavages become more entrenched, it can be expected that voters will be less likely to move away from their political allegiances.

The main outcome from the election is that Erdogan has now overshadowed his party, securing his role as President of the country. But without the AKP’s alliance with the ultranationalist bloc, it is questionable whether such power over the legislature would have been possible. As it stands, the MHP – depending on the legislative amendments put forward by other opposition parties – may check and balance the AKP’s parliamentary power.

The voting distribution across parties has not radically changed since June 2015, but the new presidential system will restructure legislative procedures and the role of the presidency. Prior to the elections, the main concern was with lifting the state of emergency. However, now that the state of emergency has been lifted, the new political system granting Erdogan extensive powers will be no more progressive than the state of emergency status was.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: The charts in this article were kindly compiled by Aslı Ünan, a PhD Candidate in Political Economy at King’s College London.The article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Sevinç Bermek – King’s College London

Sevinç Bermek – King’s College London

Sevinç Bermek is a Visiting Research Fellow at King’s College London, Department of Middle Eastern Studies.

–

Ledün Çevik – Sabanci University

Ledün Çevik – Sabanci University

Ledün Çevik is an undergraduate Erasmus+ student at King’s College London from Sabanci University.