The Southern Gas Corridor is an initiative put forward by the European Commission to transport natural gas from the Caspian Sea to Southeastern Europe and Italy. As Marco Siddi writes, the project raises several important economic, security, ethical and ecological concerns. He argues that these issues have not been properly debated at the European level, and that cheaper and less problematic sources of energy could have been discussed as options to diversify Southeast European markets.

The Southern Gas Corridor is an initiative put forward by the European Commission to transport natural gas from the Caspian Sea to Southeastern Europe and Italy. As Marco Siddi writes, the project raises several important economic, security, ethical and ecological concerns. He argues that these issues have not been properly debated at the European level, and that cheaper and less problematic sources of energy could have been discussed as options to diversify Southeast European markets.

In recent weeks, a heated debate has taken place in Italy concerning the construction of the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP). The European Commission and the Italian Confederation of Industrialists consider TAP a strategic project because, in their view, it will contribute to diversifying Europe’s imports of gas. The current Italian government, however, is divided on the issue as members of the Five Star Movement, the larger coalition party (the other coalition party being the far-right League), do not believe the project is necessary. The population of the region where the TAP is supposed to land on Italian territory, Apulia, strongly opposes the pipeline because they fear its impact on the local tourist industry and the landscape.

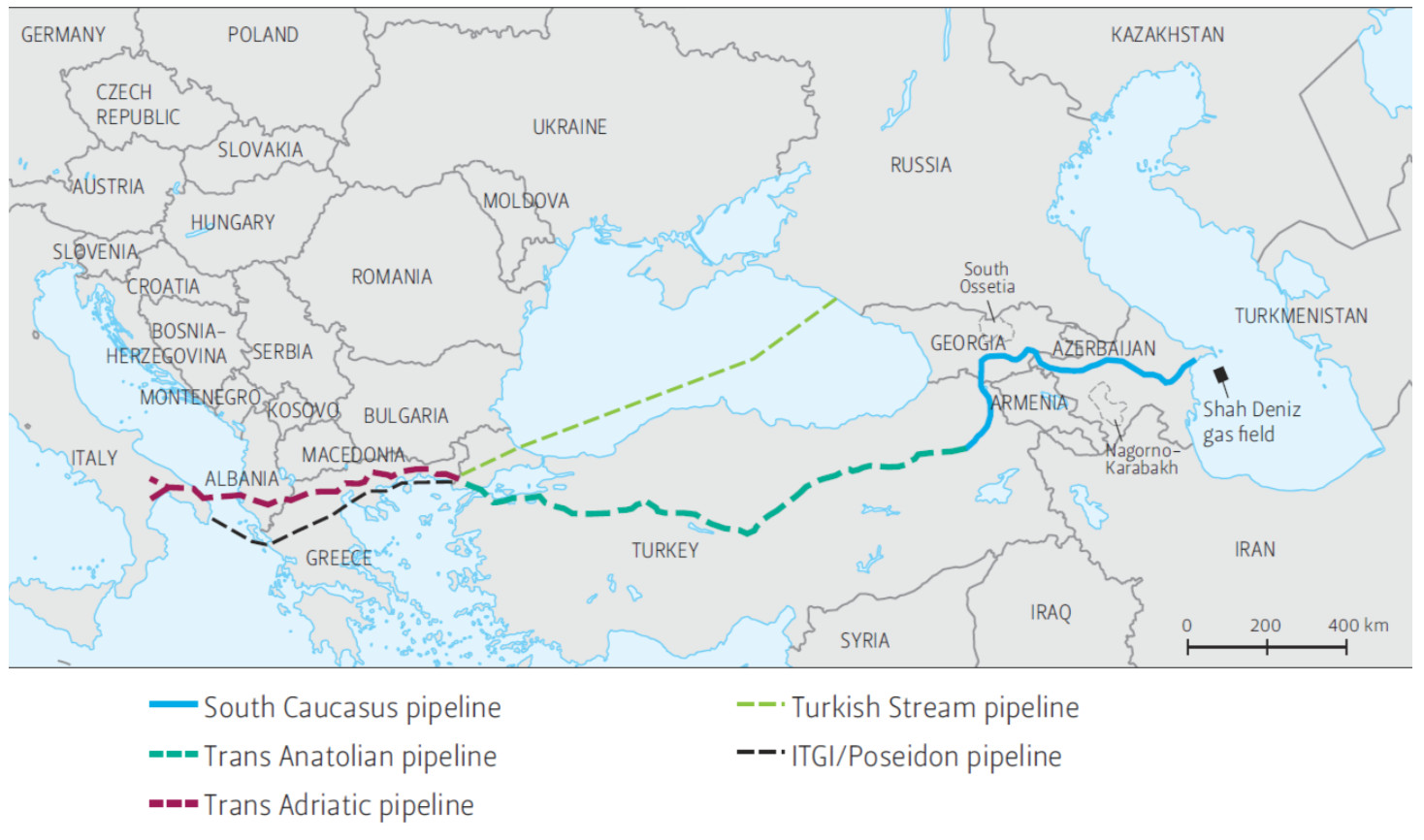

While the views of citizens most affected by the project should be treated with utmost respect, the Italian debate has focused on a narrow set of issues and neglected the broader complexities of the TAP project. This applies to both its supporters and detractors. The TAP is the final part of a larger infrastructural project known as the Southern Gas Corridor (SGC), which is meant to ship Azeri gas from the Caspian Sea to Southeastern Europe and Italy via a 3,500-kilometre route crossing the Caucasus and Turkey. Besides production facilities in the Caspian, the SGC includes the South Caucasus pipeline across Azerbaijan and Georgia, the Trans Anatolian pipeline (TANAP) across Turkey, and TAP, which runs from the Greek-Turkish border to the Apulian coast. The Southern Gas Corridor has an estimated cost of 40-45 billion dollars and involves several multinational companies (such as BP) and state-owned companies (such as the Azeri SOCAR).

Figure: The Southern Gas Corridor

Source: Produced by the author.

In a recent paper, I have outlined the challenges facing the Southern Gas Corridor. These challenges are of an economic, security, ethical and ecological nature, and have been largely ignored in the European political debate. The main reason for this is the blind support that the European Commission has given to the project. The Commission sees the SGC as a key import diversification route regardless of the controversies related to it.

From an economic perspective, the SGC faces challenges related to the availability and competitiveness of its gas. At the moment, the Shah Deniz-2 field in the Caspian Sea is the only source with substantial gas volumes that will feed the pipelines. Shah Deniz-2 should be able to reach a peak output of 16 billion cubic meters per year (bcm/y) by 2022 and then decline after 2030. Out of these volumes, 6 bcm/y have been contracted to Turkey, 1 bcm/y to each of Bulgaria and Greece and 8 bcm/y to Italy with 25-year long-term contracts.

As the research of the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies has shown, SGC gas could be price competitive in Southeastern Europe and possibly Italy, but not beyond that due to transportation costs. It would cover no more than 2 percent of European gas demand, and hence have no impact on European gas prices. Claims that the Southern Gas Corridor could cover 10-20% of European gas demand are highly unrealistic.

The strong competition of cheaper Russian pipeline gas and liquefied natural gas (LNG) from the US, Qatar and other producers are the main reasons for the limited effect of the SGC on the European gas market. The Southern Gas Corridor could have had more impact on the European market in a context of high demand, high prices and no strong competition from liquefied natural gas, as during the 2000s, when plans for it were first conceived. The picture has long changed.

Other potential suppliers of the Southern Gas Corridor do not seem to have the interest in, or be in the position of using this infrastructure. Iran and Turkmenistan have the largest gas resources (together with Russia) in the Caspian region. However, Iran is focusing on developing liquefied natural gas exports, which appear more profitable than long-distance exports via pipeline. The recent reintroduction of US sanctions further undermines prospects for Teheran’s energy cooperation with the EU.

Over the last decade, Turkmenistan has focused its gas export policy on China. Theoretically, the recent agreement on the legal status of the Caspian Sea could facilitate the construction of a Trans Caspian pipeline from Turkmenistan to Azerbaijan. However, the cost of the pipeline is estimated at 2 billion dollars, and Turkmen gas is highly unlikely to be price competitive on European markets due to transport costs. Moreover, any plans to export Turkmen gas to the West via a Trans Caspian pipeline would face competition with already existing infrastructure and a shorter route through Russia.

Economic arguments are compounded by security considerations. The route of the Southern Gas Corridor runs very close to highly volatile regions and ongoing conflicts. Nagorno-Karabakh is probably the most explosive one, not least because the Armenian and Azeri sides facing each other along the contact zone have clashed in a 4-day war as recently as April 2016. In military exercises, the Armenian air force has simulated attacks on Azeri energy infrastructure.

Further west, SGC infrastructure lies within easy reach of the separatist republic of South Ossetia, which was the theatre of the August 2008 war between Russia and Georgia. Once it has reached Turkish territory, the Southern Gas Corridor crosses areas where the Turkish army and Kurdish militias have clashed in the recent past. In August 2015, for example, an explosion damaged the local section of the South Caucasus pipeline.

Following the failed coup of July 2016 and the ensuing tensions in West-Turkish relations, Turkey itself no longer appears to be a fully reliable transit country for the EU. In the past, Turkey used its prospective role as an energy transit country in unrelated negotiations with the EU regarding Turkey’s EU accession process. The key transit role in the Southern Gas Corridor would further strengthen Ankara’s political leverage vis-à-vis the EU, which has already been boosted by the 2016 EU-Turkey migration deal. Moreover, Turkey is simultaneously cooperating with Russia on the Turkish Stream project, which is at an advanced stage and would carry large quantities of Russian gas to the same destination markets as the SGC (thereby questioning the economic viability of the latter).

The European Commission’s unwavering political and diplomatic support for the Southern Gas Corridor also entails ethical and ecological issues. The SGC involves partnerships with authoritarian regimes such as Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan, which question the EU’s proclaimed commitment to promoting norms and democratic values in its neighbourhood. From an ecological standpoint, the SGC is a very costly project that contributes to locking the EU into fossil fuel consumption in the long-term. It distracts both public funding and attention from the EU’s climate agenda.

A more careful and critical European debate would have been necessary before committing European institutions and funds to the Southern Gas Corridor, including the controversial issues presented above. Alternative, cheaper and less problematic sources of energy could have been discussed as options to diversify Southeast European markets. The fact that this has not happened calls into question both the decision-making process and the modus operandi of EU institutions.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Marco Siddi – Finnish Institute of International Affairs

Marco Siddi – Finnish Institute of International Affairs

Marco Siddi is a Senior Research Fellow in the European Union Research Programme at the Finnish Institute of International Affairs.