Corruption is a persistent problem in many European countries, but could improving the representation of women in politics offer a potential answer? Drawing on recent research, Monika Bauhr explains that a clear link can be identified between the share of women in office and a reduction in corruption, which may be attributable to the differing priorities of women when it comes to public service delivery and the breakup of male-dominated networks that are detrimental to their political careers.

Corruption is a persistent problem in many European countries, but could improving the representation of women in politics offer a potential answer? Drawing on recent research, Monika Bauhr explains that a clear link can be identified between the share of women in office and a reduction in corruption, which may be attributable to the differing priorities of women when it comes to public service delivery and the breakup of male-dominated networks that are detrimental to their political careers.

Despite massive investment in anticorruption measures around the world, the impact of these efforts has been meagre at best. In response to the failure of many traditional anticorruption measures, experts have therefore promoted more ‘indirect’ approaches to anticorruption. Instead of seeking to directly monitor and punish corrupt behaviour, anticorruption efforts may benefit from instead supporting attempts to change underlying conditions and structures that perpetuate corrupt systems. Increasing female representation is one of these indirect approaches to anticorruption. This is because, as I and my co-authors illustrate in a recent study that builds on several previous studies in this field, a strong link can be identified between the share of women in office and control of corruption.

Why do women in elected office reduce corruption? We believe women that attain public power seek to pursue two political agendas in particular: the improvement of public service delivery, notably in sectors that benefit women, and the break-up of male dominated collusive networks that are detrimental to their political careers. Improvements in public service delivery reduce the need for petty corruption and the breakup of collusive networks reduces grand corruption.

Figure 1: How women’s representation in parliament reduces corruption

Note: For more information, see the accompanying journal article.

The political agenda explanation that we propose can explain why women in elected office reduce both petty and grand corruption. It also provides a necessary alternative or complement to existing explanations. Several studies show that women are typically more risk averse than men and therefore less likely to engage in criminal behaviour of all kinds. While this explanation most certainly may explain some of the differences between male and female politicians, it is weakened by the fact that elite women, especially those that assume office in male dominated sectors, may not be the most risk averse among women.

Furthermore, and of perhaps even greater importance, fighting corruption can also be extremely dangerous. Mobilising against corruption creates very powerful enemies, especially in highly corrupt contexts. It is therefore less likely that the task of fighting corruption would be taken on by particularly risk averse actors. Of course, the fact that women tend to be more strongly punished for engaging in corruption and their generally more pro social value orientation may also constitute viable explanations.

Our analysis uses data on the share of locally elected female representatives in 182 European municipalities. To measure petty corruption, we use citizen-reported experiences of petty corruption from a regional level survey of 85,000 Europeans. Our measure of grand corruption uses data on corruption risks in close to all major public procurement contracts awarded in these municipalities.

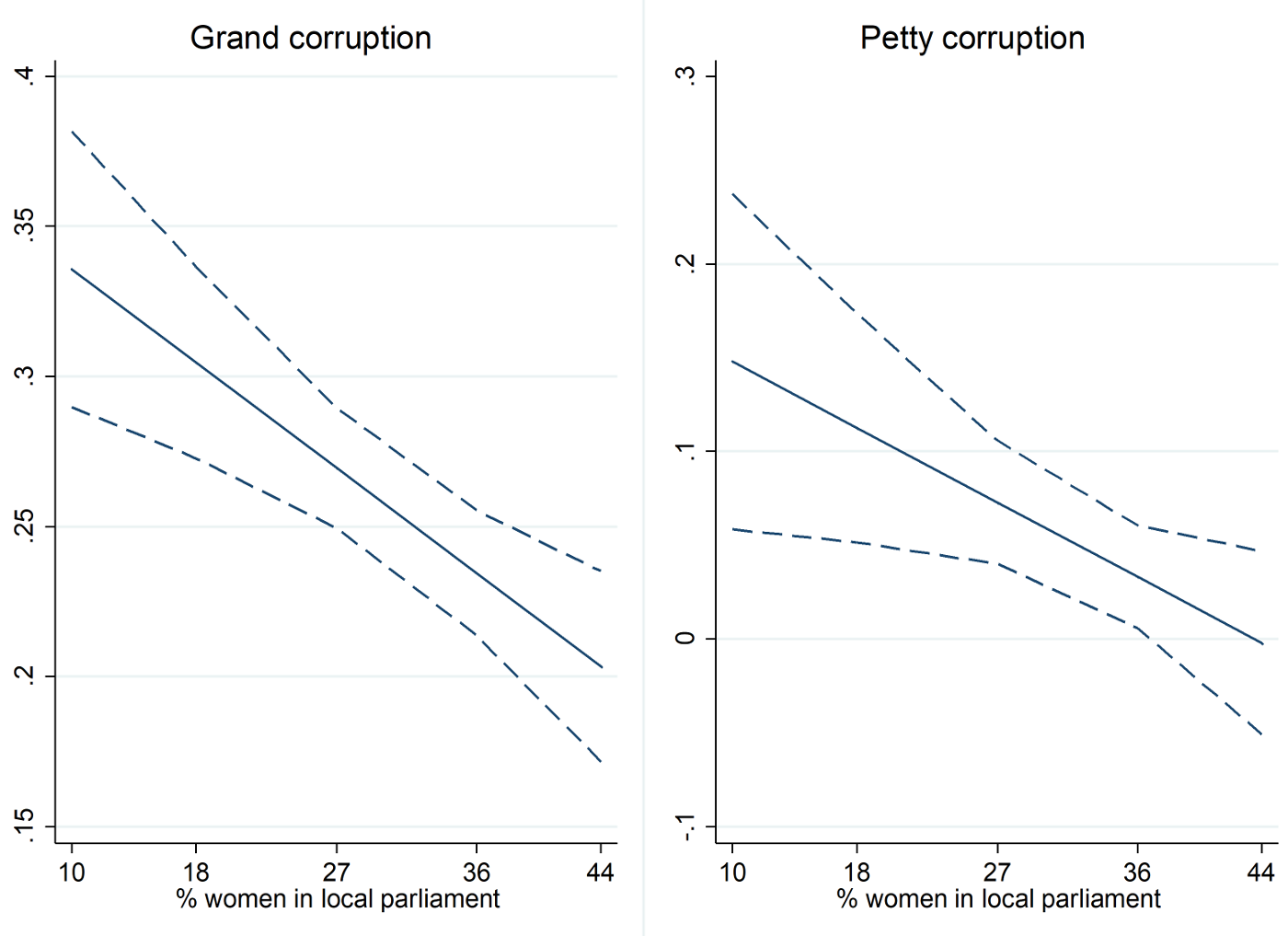

We find strong evidence that the proportion of local female political representatives is associated with lower levels of both grand and petty corruption. Figure 2 shows that as the share of females in locally elected councils increases, the level of both grand and petty corruption decreases. For instance, in the regions where the local council has more than 30% of women representatives, less than 10% of the population has experienced petty corruption.

Figure 2: The presence of more women in local parliament reduces both petty and grand corruption

Note: For more information, see the accompanying journal article.

We also find that there are important differences between public services. Female representation decreases the level of corruption in health and education but not in law enforcement. This may be because women are on average more likely to be exposed to corruption in education and health. Furthermore, we show that while bribe paying decreases overall, bribe paying among women drops more sharply than bribe paying among men. For example, a woman is roughly 3.5 times more likely to pay a bribe in education when the share of female representation is at its lowest compared to when it is at its highest.

Figure 3: Female representation is strongly associated with reduced probability of experience with petty corruption in health and education, particularly among women

Note: For more information, see the accompanying journal article.

While gender equality is a desirable end in its own right, our study provides evidence that it is also associated with a stark reduction in both petty and grand corruption. We believe that the political agendas that women pursue can explain the drop in corruption levels. Women are more vested in public service delivery because of their greater care taking obligation and their careers are affected by being excluded from male dominated networks. This makes them fight both petty and grand corruption.

Two important issues remain unresolved, however. First, the causal evidence is thus far rather limited, since most studies build on observational data. For instance, low corrupt systems may facilitate the inclusion of women in office. We also know comparatively little about whether the beneficial effects of including women in office will last over time. These questions are of key concern for all policy makers, aid organisations and human rights activists that seek to further political empowerment in contexts where these measures may encounter open or hidden resistance, as well as for researchers in this field.

Finally, our most recent research uses a unique methodological approach to study these issues at the municipal level in France. This study finds that women in elected office do in fact reduce corruption. However, the beneficial effects are weakened over time as newly elected female mayors are driving the results. This suggests that the positive effect of including women in office may be attributable to women being newcomers to politics, and that women that manage to adapt to corrupt networks stand a better chance of being reelected. This shows that the inclusion of women in office will reduce corruption, but that further efforts are needed to make this effect sustainable over time.

For more information, see the author’s accompanying study in the European Journal of Political Research (co-authored with Nicholas Charron and Lena Wängnerud)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: © European Union 2018 – European Parliament (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

_________________________________

Monika Bauhr – University of Gothenburg

Monika Bauhr – University of Gothenburg

Monika Bauhr is an Associate Professor at the department of Political science, University of Gothenburg, and the head of the Quality of Government Institute.

The outragously sexist and unsubstantiated claim here if anyone missed it, is that women are honest and trustworthy creatures while men simply are not.

It’s quantitative research that shows the higher the number of women in politics the lower corruption levels. Calling it “unsubstantiated” or getting offended by what the data says isn’t a valid response whichever way you slice it.

The real question is why the results are the way they are: are women actually more honest, is it really a causal relationship (or are less corrupt political systems more likely to have more women because they’re more fair/open), is it something to do with the self-interest of women and how that relates to existing networks of corruption that may be more likely to be dominated by men, is it because female politicians are more likely to be “new” and therefore less entrenched in existing networks. The author says all of that in the article. Getting triggered by a title and jumping straight to the comment section is never very sensible.

When I looked into the research it was based on a telephone survey which will in itself pick up on the pejudices and sterotyping of the callers questioned.

I delved further into the UK figures and what I found was interesting.

Women have overtaken men in conviction numbers for “dishonest representation” and “false representation”.

That is a fact you can find here, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/380098/offence-analysis-7.xls

Matthew, again this isn’t really a substantive response for the following reasons:

1. You haven’t explained why using survey data makes a study invalid. It’s a pretty bold claim that can’t be brushed under the carpet with a line about “prejudices and stereotyping”.

2. The survey data is being used to determine which areas have higher levels of corruption than others. It’s not being used to say women reduce corruption, it’s being used to get a picture of where corruption exists. That data is then compared with figures on women’s representation in politics. There’s also an entirely different measure that doesn’t use survey data for determining where grand corruption exists.

3. Even if for some reason we want to say that all survey data is useless and doesn’t count (again, why?) there’s no reason why that would produce a result where areas that have low corruption reported should have higher levels of women in politics. They’re separate variables. For that to be true there would have to be some unseen phenomenon at play where areas that have more women in politics have citizens that seem to be less willing to report corruption (and what does any of that have to do with the prejudices of respondents in any case?)

If you want to criticise methodology you have to bring something to the table that’s meaningful. Nobody here is interested in getting into a strange debate about whether women are more corrupt than men (or vice versa). This isn’t a gender politics flame war, it’s quantitative research that shows a trend: the two valid ways to respond to it are either by pointing out meaningful flaws in the research (and ideally improvements that can be used to get better results) or proposing meaningful explanations for why the results are the way they are.

Let me expand on my thoughts of the telephone survey data.

If you ask tens of thousands of people, if they’ve offered a bribe in the last 12 months and if to to what gender, what does that actually tell you?

If the answer after yes if more often than not to men, it cannot be deduced that men are more likely to accept a bribe, just that they’re more likely to be offered one.

That could be down to the presumption of the person bribing, that a man is more likely to take one.

That is what I meant about picking up on the prejudices of the people being surveyed.

“If the answer after yes if more often than not to men, it cannot be deduced that men are more likely to accept a bribe, just that they’re more likely to be offered one.”

This isn’t how the research was conducted. The phone survey was to assess which areas had more corruption than others, not whether men or women were offered bribes. That data (and an entirely different set of data for grand corruption that didn’t use phone surveys) was then referenced against the number of women in politics in a given area to see if there was a pattern.

Thanks! We do indeed specifically and explicitly argue against the position that women are more honest and trustworthy than men by nature, that is the main contribution of the political agenda theory that we develop in our work. Furthermore, the data that we use is based on women and mens reported experiences of bribery (for the measure on petty corruption) and corruption risks data based on actual public procurement statistics (for the grand corruption measure).