Party competition in the European Parliament has changed substantially in the aftermath of the Eurozone and migration crises. While the parliament was once characterised by a split between parties on the left and right, parties are also now sharply divided over their policies on immigration and European integration. Drawing on new research, Alexia Katsanidou and Zoe Lefkofridi illustrate how these shifting dynamics have affected the coherence of European party groups and the competition between them ahead of the 2019 European Parliament elections.

Party competition in the European Parliament has changed substantially in the aftermath of the Eurozone and migration crises. While the parliament was once characterised by a split between parties on the left and right, parties are also now sharply divided over their policies on immigration and European integration. Drawing on new research, Alexia Katsanidou and Zoe Lefkofridi illustrate how these shifting dynamics have affected the coherence of European party groups and the competition between them ahead of the 2019 European Parliament elections.

Up until the Eurozone crisis, politics in the European Parliament had been dominated by the left-right dimension. The crisis, however, brought about the politicisation of the issue of European integration across the European Union. This became obvious in the 2014 European Parliament elections. National parties, which might have previously either ignored or attempted to shut down the issue, were forced, amidst the crisis, to take a clear stance in favour of or against European integration.

But how did the intense politicisation of the European project impact the coherence within and competition between party groups? After the election, representatives of national parties elected in each of the member states formed transnational party groups. On the issue of European integration, these groups showed high levels of coherence in their ranks, with most of their member parties placed on the same side of the issue.

In fact, this was the issue that exhibited the highest levels of coherence within these groups, except for two groups on the left, namely the Greens and European United Left-Nordic Green Left (GUE-NGL) and one group on the right, the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR). At the same time, this issue proved to be the most divisive between groups: European integration united Europhiles against Eurosceptics and offered a clear distinction between the two. No middle ground was apparent.

What about left-right issues that have been prominent in transnational and national political debates, such as immigration, welfare, and LGBT rights? Overall, the composition of the parliament after the 2014 elections reflected typical left-right competition patterns: parties on the left (Greens, GUE-NGL) tended to be in favour of immigration, welfare and LGBT rights, while parties on the right (Europe for Freedom and Direct Democracy/EFDD) tended to be against immigration, welfare and LGBT rights. While competition between groups on such issues exists, an examination of coherence within each group reveals important internal divisions that will likely prove decisive for the future of the European party system.

First, the question of whether immigration should be made more restrictive was divisive for the three largest groups during the 2014 elections: the European People’s Party (EPP); the ECR, which brings together Conservatives and Christian Democrats; and the Socialists and Democrats (S&D). The divisive power of this issue would later be reflected in the rift caused by the so-called ‘refugee crisis’ that started in summer 2015 – a division that still haunts Europe today.

Second, the S&D was also divided over traditional social democratic concerns, such as the question of whether social programmes should be maintained at the cost of higher taxes. This relates to the North vs. South conflict over austerity as a solution to the Eurozone crisis; while this North-South gap seems to pose problems for coherence on welfare within the S&D, this is not the case within the EPP. Third, on the controversial issue of same-sex union, only the Greens and the EFDD enjoyed coherence.

Differentiation and coherence: How different was the 2014 European Parliament from its predecessor?

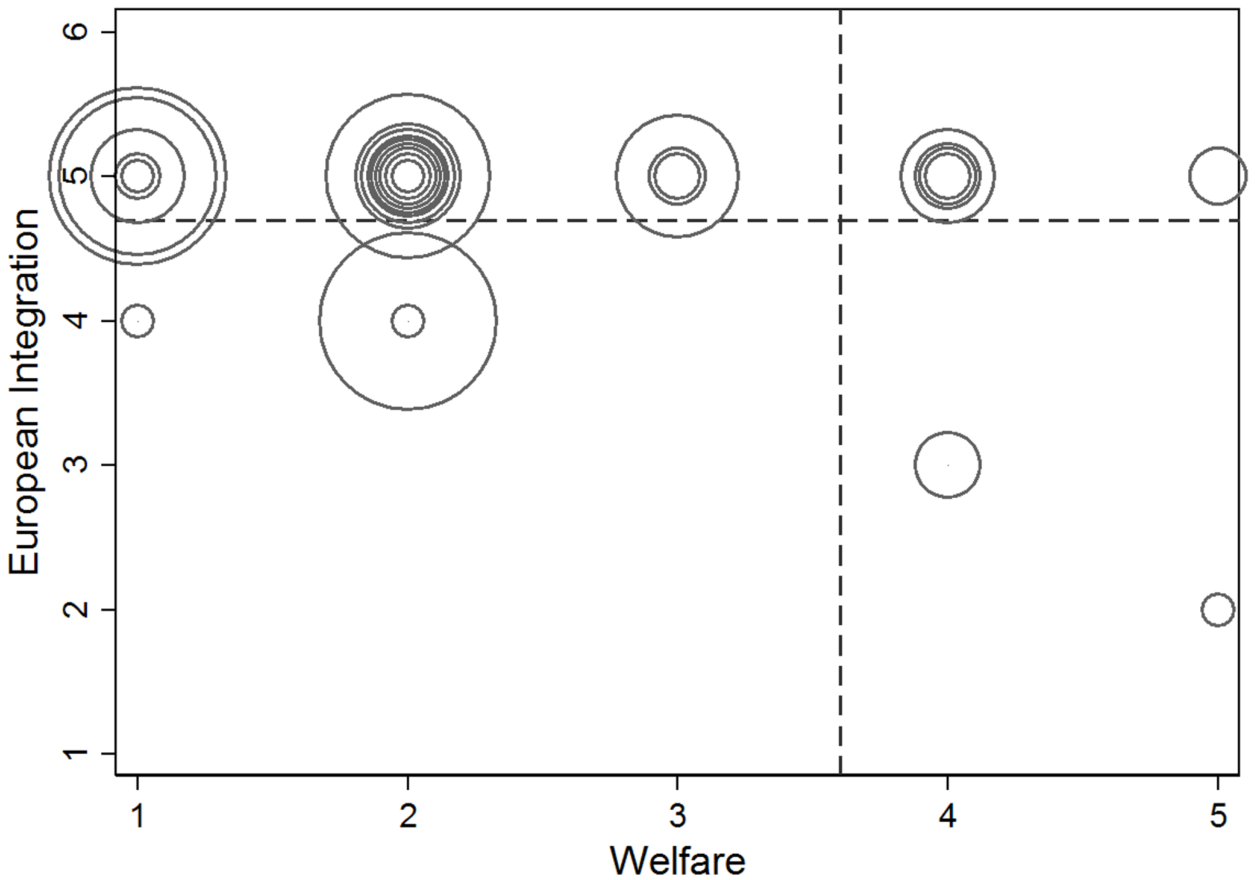

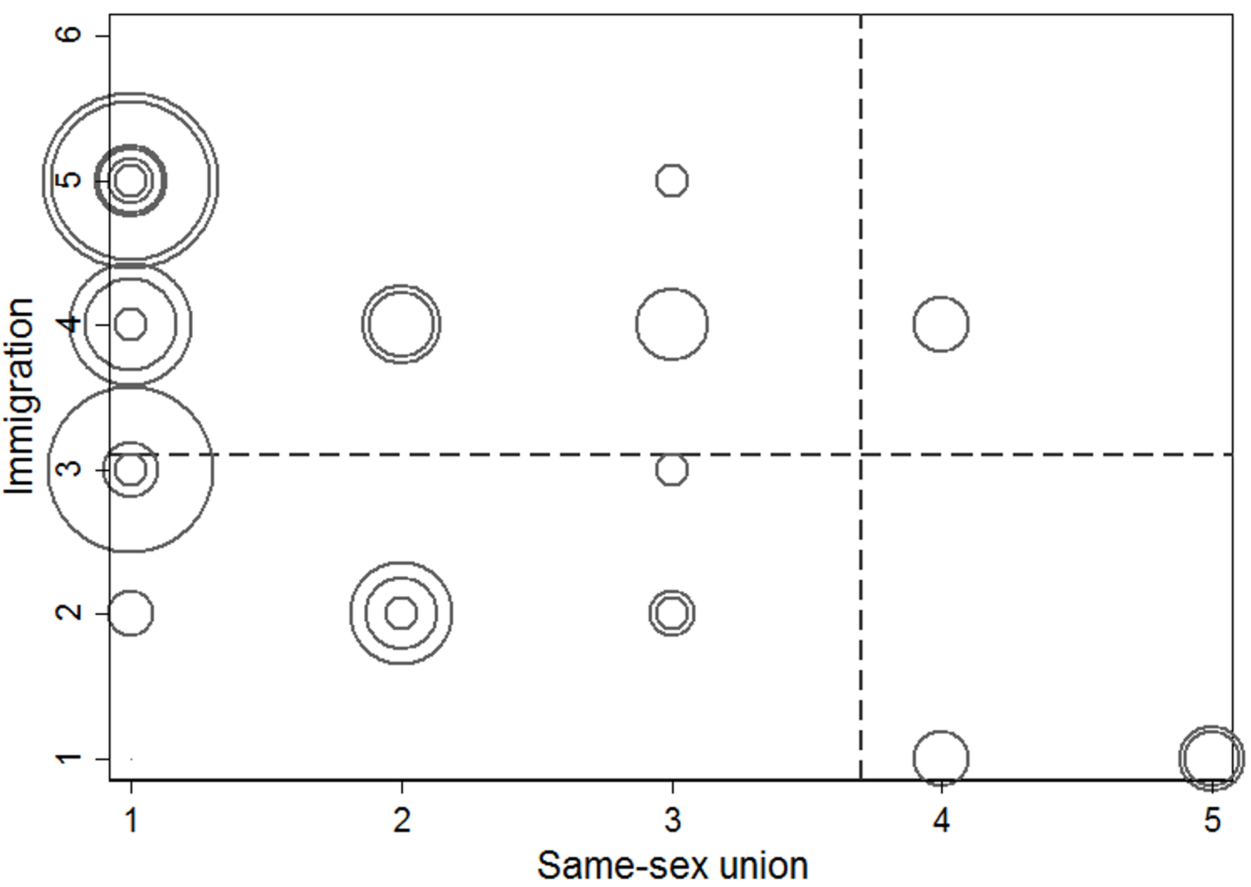

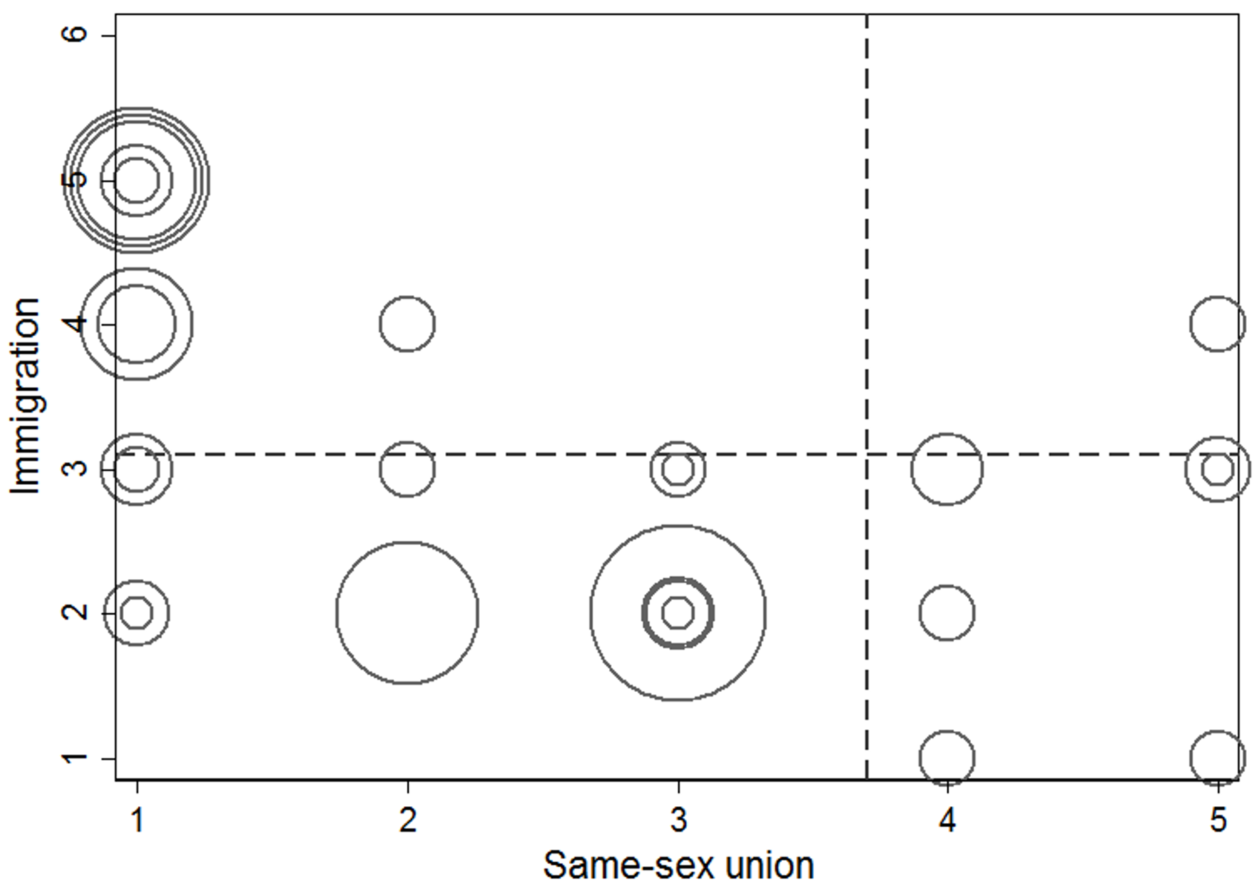

To illustrate changes in levels of coherence between the 2009 and 2014 European elections, we use the example of the winner of both elections: the EPP. The positions of EPP members on four issues in 2009 and 2014 are visualised in Figures 1-4, where each member party is presented with a bubble, whose size depicts the number of MEPs elected by this party. Figures 1 and 2 concern the parliament after the 2009 elections and Figures 3 and 4 concern the parliament after the 2014 elections. A bigger bubble represents a bigger member party, while a small bubble stands for a smaller party.

Figure 1: Positions of national parties within the European People’s Party in 2009 (European integration / welfare)

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying journal article.

Figure 2: Positions of national parties within the European People’s Party in 2009 (immigration / same-sex union)

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying journal article.

In detail, Figure 1 shows where EPP party members were located on the issues of European integration (vertical axis) and welfare (horizontal axis) in 2009: on the issue of European integration there were only three outliers: the Finnish Christian Democrats, who tended to be against European integration, the Slovak Party of the Hungarian Coalition and the Swedish Moderate Party, who occupied neutral positions.

Figure 2 shows the positions of EPP members on immigration (vertical axis) and same-sex union (horizontal axis) in 2009. On the issue of immigration, we see that the EPP was divided in 2009: ten parties positioned themselves against more restrictive immigration rules and eighteen parties in favour of them. Four parties held a neutral position. The issue of same sex union was also a divisive issue for the EPP, which relates to many domestic Churches’ recalcitrant stances on this matter. In 2009 only four parties opposed the main party line taking a liberal stance.

Figure 3: Positions of national parties within the European People’s Party in 2014 (European integration / welfare)

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying journal article.

Figure 4: Positions of national parties within the European People’s Party in 2014 (immigration / same-sex union)

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying journal article.

Figure 3 presents EPP members’ positions on European integration and welfare in 2014. It shows member parties coiling together on the pro-EU side, with only two outliers, the Hungarian Fidesz and the Alliance for Croatia (a coalition of small right-wing parties). Figure 4 shows EPP members’ positions on immigration and same-sex union in 2014: though the division witnessed in 2009 remained, many parties moved to the middle ground; eleven parties endorsed restrictive immigration policies, ten parties opposed this, and seventeen have a neutral position. LGBT rights became more contentious within the European Parliament in 2014, with seven parties supporting same sex union.

The comparison between 2009 and 2014 also shows that connecting the European election to the Commission presidency (via the Spitzenkandidaten process) did not produce the desired results, at least not in the short run. Our analysis provides no indication that this innovation impacted on the differentiation or coherence of European party groups. To summarise, our analysis of data from 2009 and 2014 shows that issue competition, an element essential for the development of the EU-level party system, is present: for four important issues presented here, there are European party groups on both sides. Coherence within groups is also existent, though not perfect. To be sure, all political parties have renegades on one or the other issue. For European party groups, issues that are both divisive, like immigration, and politicised on the European level are the ones that can cause the most violent splits.

What can we expect in the upcoming 2019 European elections?

Less than a year ahead of the 2019 European elections, the European People’s Party faced a motion against one of its most successful members, Fidesz. Fidesz has shown unwillingness to align with the pro-Integration EPP line and the circumstances of the European migration crisis since 2015 have allowed it to further harden its line: the party’s leader, Viktor Orban, presents himself as the defender of Hungary and Europe against Muslim migrants. This, however, has developed into a significant rift between EU member states – and EPP members in particular – over the EU’s ability to contain the migration crisis and “protect Christian values”. The motion against Hungary was contentious for the EPP as a party group, but also for each of its member parties, which were called to take a stance in favour of or against Orban, and consequently, his concept of democracy and vision for Europe.

What is important to remember is that European party groups are sensitive to dynamics in national party systems. Under domestic pressure from electorally successful radical right parties that thrive through the securitisation of migration, many EPP members, such as the Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP) under the leadership of Sebastian Kurz, have toughened their language on immigration. At the same time, however, S&D members also lose votes to radical right parties on the issue of welfare, which these parties have connected to immigration by advocating “exclusive solidarity” (e.g. natives- only welfare).

Eurosceptic radical right parties have entered the (traditionally social democratic) welfare issue space and pressure conservatives and Christian Democrats on security and immigration. Hence, the question that arises for the 2019 election is how will the national political parties that rebuilt Europe after World War II react to the double challenge posed by Eurosceptic radical right parties? The main problem is that Euroscepticism is connected both to the economic dimension, with pro-welfare attaching to Eurosceptic attitudes, and the socio-cultural dimension, where restricting immigration becomes synonymous with opposing the EU. Which type of Euroscepticism dominates in the national party system depends, to an extent, upon the European North vs. South divide as it was shaped by the Eurozone crisis.

The significant misfortune for EU-level party democracy (and the EPP and S&D Groups in particular) would be that each national party solves this equation depending on the special conditions in its own national party system without central coordination within the European party group where it belongs. Such a strategy might help in the national arena, but in the long-term it would not only harm the quality of representation at the European level, but also the European project itself.

For more information, see the authors’ recent article in the Journal of Common Market Studies

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: © European Union 2018 – European Parliament (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

_________________________________

Alexia Katsanidou – University of Cologne

Alexia Katsanidou – University of Cologne

Alexia Katsanidou is a Professor of Empirical Social Science at the University of Cologne and the Scientific Director of the department Data Archive for the Social Sciences at GESIS – Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences.

Zoe Lefkofridi – University of Salzburg

Zoe Lefkofridi – University of Salzburg

Zoe Lefkofridi is an Assistant Professor of Comparative Politics at the University of Salzburg and Associate at the European Governance and Politics Programme of the European University Institute in Florence.