The ‘Yellow Vests’ protest movement which began in France at the end of 2018 has uncovered widespread anger among French citizens. But as Nicolas Duvoux and Adrien Papuchon explain, it is difficult to fully capture the scale of this resentment from an analysis of available poverty measures. Instead they suggest that an indicator of ‘subjective poverty’ is required to gain a full understanding of the roots of the movement.

The ‘Yellow Vests’ protest movement which began in France at the end of 2018 has uncovered widespread anger among French citizens. But as Nicolas Duvoux and Adrien Papuchon explain, it is difficult to fully capture the scale of this resentment from an analysis of available poverty measures. Instead they suggest that an indicator of ‘subjective poverty’ is required to gain a full understanding of the roots of the movement.

Starting in November last year, the ‘Yellow Vests’ protest movement has revealed deep and intense anger towards the government and elites among the working classes in France. Yet, available poverty measures both at the national and EU levels do not accurately capture the reasons why such social resentment has erupted.

Instead, an indicator of subjective poverty offers a better route for measuring the widely spread social insecurity that manifested itself during the protests. Means-tested assistance schemes that have developed for three decades in France have failed to address this subjective poverty. Thus, this scientific challenge is also a public policy one.

Inadequate poverty measures

The question of who qualifies as ‘poor’ has been much debated in the human and social sciences. In France, any individual living in a household whose standard of living is less than 60 per cent of the median standard of living is considered poor: in 2016, this represents an income of €1,026 per month for one person, which would cover around 14 per cent of the population.

Poverty now disproportionately affects children (19.8 per cent), young adults (19.7 per cent between 18 and 29 years) and single-parent families (34.8 per cent). It is concentrated in densely crowded urban areas, whose inhabitants have not participated in the movement. It is an indicator of inequality, which measures the gap to average or intermediate incomes, but fails to capture the extent to which low-income workers and retirees struggle to make ends meet.

There is also poverty in living conditions. This is decreasing due, in particular, to improvements in the quality of housing. Yet, housing is particularly expensive in France when compared to other European countries. As such, this measure does not help us to understand the social underpinnings of the Yellow Vests movement.

Subjective poverty and social inequalities

Data from the Health and Solidarity Ministry’s Directorate for Research, Studies, Assessment, and Statistics (DREES) can help address this problem. The opinion barometer conducted by DREES offers one of the most robust datasets on public perceptions of social cohesion, inequality and welfare state policies in France. It allows the self-identification of poverty to be measured based on the following question: “Personally, do you consider that there is a risk that you will become poor in the five next years?”

While relative income poverty indicates the share of income that is distant from intermediate or median incomes, the sense of poverty, which affects about 13% of the population in the 2015-17 figures, highlights persistent social insecurity and a degraded vision of the future. Monetary poverty is an indicator of inequality, while subjective poverty is an indicator of insecurity.

The main contribution of this subjective measure of poverty is to question the most common view of poverty which, by focusing on situations of prolonged distance from the labour market, neglects the high percentage of people who consider themselves poor. Here the vulnerability felt by workers in the service or industrial sectors appears to be highly significant given France distinguishes itself in international comparisons by highlighting a fairly low level of in-work poverty. Means-tested assistance schemes that have been developed for three decades in France have failed to address this subjective poverty.

Figure 1: Subjective poverty in France by employment status (click to enlarge)

Note: Figures are for individuals aged 18 and over living in metropolitan France. Source: Opinion barometer of the DREES, 2015-2017. (*) Also includes Professionals, Farmers and Storekeepers.

This indicator of subjective poverty helps demonstrate the importance of key drivers of socio-economic inequalities. If, in France, those who are above the age of 60 have a lower average level of poverty than the general population, thanks to the comparatively generous public pension system, housing status has a clearly stronger impact on subjective poverty among retired people. Subjective poverty captures how home ownership is shaping inequality in contemporary France and it does so more accurately than objective poverty.

Rethinking subjective poverty

Several of the subjective measures available in the current discussion on poverty have been developed in various contexts over the previous decades. More recently, a method based on the elaboration of ‘reference budgets’ has been developed as a means to capture the adequacy of resources of households.

However, a common feature of most of these approaches is that they measure social norms (the minimum necessary income to live decently in a given society) rather than an individual’s perception of their own social position. None of these indicators captures adequately the self-identification as poor that most accurately defines a subjective poverty indicator. This self-identification is exactly what can be found and what can help understand the scope and depth of social insecurity among French working classes.

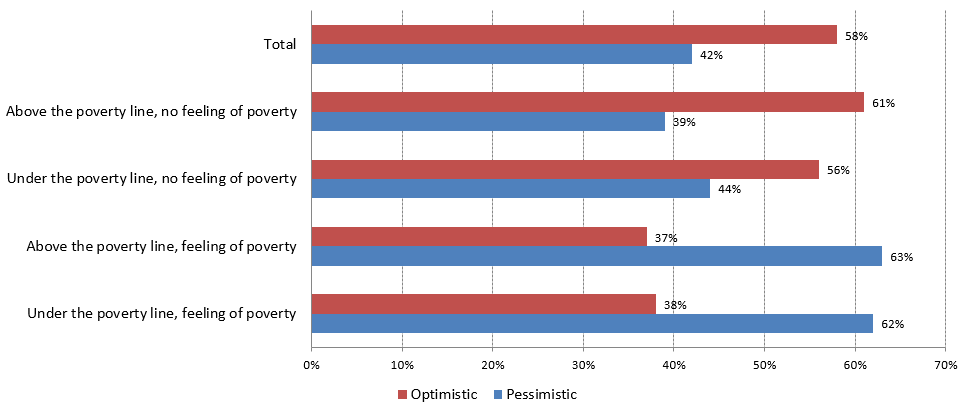

Figure 2: Subjective poverty and optimism/pessimism about the future

Note: Figures are for individuals aged 18 and over living in metropolitan France. Source: Opinion barometer of the DREES, 2015-2017.

Lastly, contrary to downward mobility, those who feel poor not only have a negative view of their past trajectory but are also disproportionately pessimistic about the future. Thus, this indicator provides a wider account of the social experience of those who are disadvantaged in society. This is the sense of despair that the Yellow Vests movement has become an expression of. Implementing means-tested assistance schemes cannot be considered a satisfying answer to the growing social instability and feeling of injustice in French society.

For more information, see the authors’ recent paper in Revue Française de Sociologie

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, the London School of Economics, or the authors’ organisations. Featured image credit: Patrice CALATAYU (CC BY-SA 2.0)

_________________________________

Nicolas Duvoux – Université Paris 8

Nicolas Duvoux – Université Paris 8

Nicolas Duvoux is Professor of Sociology at Université Paris 8.

–

Adrien Papuchon – DREES

Adrien Papuchon – DREES

Adrien Papuchon is a sociologist based in the French Ministry of Solidarities and Health at the Directorate for Research, Studies, Assessment, and Statistics (DREES). He completed his PhD in sociology at Sciences Po.

Very well put indeed, and stated in simple words. Altogether: is there no consistent figure about home ownership among retired people as opposed to other groups? This indeed would strengthen your line of arguing.

Poverty and inequality are not the only reasons for the resentment of the Macron regime; these are just sub-parts of the grander problem of a government that is uncaring to its own people, and instead cares more for the unknown person from far far away. This form of governing by Macron is endemic to those who wish to be the ruler of a global government, in lieu of representing his own people who elected him AND for whom he has a Constitutional duty to represent.

When such a survey and attending analysis is published, it would be immensely helpful if the essential data relevant to this issue were to be provided as well. Poverty, subjective or otherwise, in this context, relates to financial wherewithal and economic prospects as well as an intuitive and reasoned sense of entitlement denied. The data I refer to is usually hidden from public view, because the public is not allowed to know. The measures of poverty and relative poverty depend on a great many variables, many of which are not acknowledged or made explicit in public discourse. Some clever politician, was it Cameron, once said “we’re in this together “. Generally, the lower socio-economic strata in western society are peopled by people with an innate sense of fairness. It might be claimed that people in the higher socio-economic strata also have an innate sense of fairness, in which case they have successfully disengaged same for the duration, though, of course, there are always exceptions.

Now, for subjective poverty to be dealt with, the essentially disenfranchised must be able to judge for themselves whether people in the higher socio-economic strata are pulling their weight and are not over-compensated. For this comparative exercise to have any meaningful effect, the financial and economic data pertaining to the higher socio-economic strata need to be available for scrutiny. It has been popular with neoliberal elements in government to publish figures relating to benefits paid out by the government. Never are these figures broken down to specify where the money goes. This is important to know, as it then allows those who suffer from subjective poverty to see who gets what. Likewise, the total income pertaining to the nation’s government apparatus is never specified as to where it is earned or obtained and never is the spending of it specified as to which socio-economic class gets what, why and how much.

If, for instance, economists or academics are working in a country such as France or the UK, it is important to know how many are working, who they are working for, what they are, in fact, doing and who pays for it. The yellow vests are protesting, which is a clear sigh they are dissatisfied with the way the benefits of the nation-state are shared, or not shared, as the case may be. Protesting is a sign of an either justified or unjustified sense of lack of political purchase or hold on the nation’s affairs. Just now, it looks like a sign of the extent to which people have realised they are left behind.

“The data I refer to is usually hidden from public view, because the public is not allowed to know.”

This is a very very weird thing to write. Who has decided “the public is not allowed to know”? The data source is given under the graphs and the study is linked to at the end.

@ Theo Eps. The data I refer to is obviously nothing to do with the data provided above, the which is obviously not hidden from public view. Did you read all of my the above comment? It doesn’t look like it, judging by your comment, Theo.

The share of the population that is considered poor by income-based standards is 14%, this says, while a similarly sized 13% perceives themselves to be poor; but as the authors lay out clearly, these are only very partially the same people. That made me curious about something that doesn’t seem to be clarified in the piece: what shares of the population fall exactly in the four brackets that are charted out in Fig 1? I imagine easily a majority of the French falls in the first bracket (above the poverty line and doesn’t feel poor), but what’s the distribution across the other three brackets?