Support for radical right parties is often assumed to carry a degree of social stigma, which means that individuals are likely to privately support them but refrain from stating such support to others. But does this hold true once a party enters a national parliament? Drawing on a new study, Vicente Valentim illustrates that once a radical right party enters parliament they can effectively become normalised, with supporters more likely to report their backing for the party in surveys.

Support for radical right parties is often assumed to carry a degree of social stigma, which means that individuals are likely to privately support them but refrain from stating such support to others. But does this hold true once a party enters a national parliament? Drawing on a new study, Vicente Valentim illustrates that once a radical right party enters parliament they can effectively become normalised, with supporters more likely to report their backing for the party in surveys.

The success of radical right parties has been increasing and spreading in recent years. From peripheral political groups, they have grown to become central to the policymaking process in many countries. But has this electoral success ‘normalised’ these parties, reducing the stigma associated with the radical right and making individuals more confident in engaging in public demonstrations of support for such parties?

In a recent paper, I contend that it has. I argue that the rhetoric and policy positions of radical right parties openly defy established social norms. As breaching such norms comes with social sanctions, voters are likely to privately support the party and its policies but refrain from engaging in public manifestations of that support. However, the parliamentary entry of a radical right party can represent a crucial step in the normalisation of radical right discourse and ideology. Being part of the legislative body of the country is a signal of acceptance that can make voters perceive social norms against the expression of radical right support as being weaker. This can make individuals more likely to openly show their support for the radical right.

This argument, however, is hard to test empirically because one cannot know what an individual’s true preferences are if they are consciously concealing them. I overcome this problem with three complementary studies. The first provides comparative evidence of my argument, taking advantage of the fact that the vote share for radical right parties is consistently underreported in post-electoral surveys. This is likely to happen because a survey interview is still a social interaction and, as such, social norms are likely to influence the answers provided by respondents. They can feel judged by the interviewer and try to provide what they perceive as the socially desirable answer.

Taking this into consideration, I have built a measure (which I call ‘reported vote’) that captures the proportion of the official vote share for each radical right party that is reported in post-electoral surveys in 21 countries. I then checked if this proportion increases after radical right parties enter parliament by employing a regression discontinuity design – an analysis that compares parties just above and just below the legally fixed electoral threshold in their country.

A graphical representation of these analyses is shown in Figure 1 below. The x-axis represents how many percentage points away from the electoral threshold (above or below) each radical right party was. The y-axis represents the proportion of the official vote for that party that was reported in each post electoral survey. The analyses show that a radical right party entering parliament makes individuals substantively more likely to openly show support to them. For every ten individuals that voted for a radical right party, three to four more (depending on model specification) were willing to say they did so if the party narrowly made it to parliament than if the party narrowly failed to make it.

Further analyses suggest that these results are not being driven by differences in the sociodemographic characteristics of individuals that are successfully contacted when radical right parties are in and outside of the parliament. They also suggest that the results are not driven by radical right parties that enter parliament being more moderate than those that fail to do so.

Figure 1: Supporters of radical right parties present in national parliaments are more likely to indicate their backing for the party in surveys

Note: Each triangle/circle represents a radical right party. Those parties on the left half of the chart (circles) had official vote shares below the threshold required to enter their national parliament. The parties on the right half (triangles) had official vote shares above this threshold and could enter parliament. The y-axis shows what proportion of the official vote for each party was indicated in post-election surveys (‘reported vote’), suggesting that when a radical right party enters parliament, its supporters are more willing to state they back the party. For more information see the author’s accompanying paper.

A second study takes a deeper look into the individual-level mechanism. In it, I take advantage of some post-electoral surveys that, inside the same country, employed different modes of interview to survey different respondents. Some of these modes included an interaction with the interviewer – such as interviews over the phone or face-to-face – which I call public modes of interview. Others included no interaction – such as mail-back, online, or self-administered surveys – which I call private modes of interview. This difference is crucial because social norms should be expected to interfere less with private behaviour such as private modes of interview.

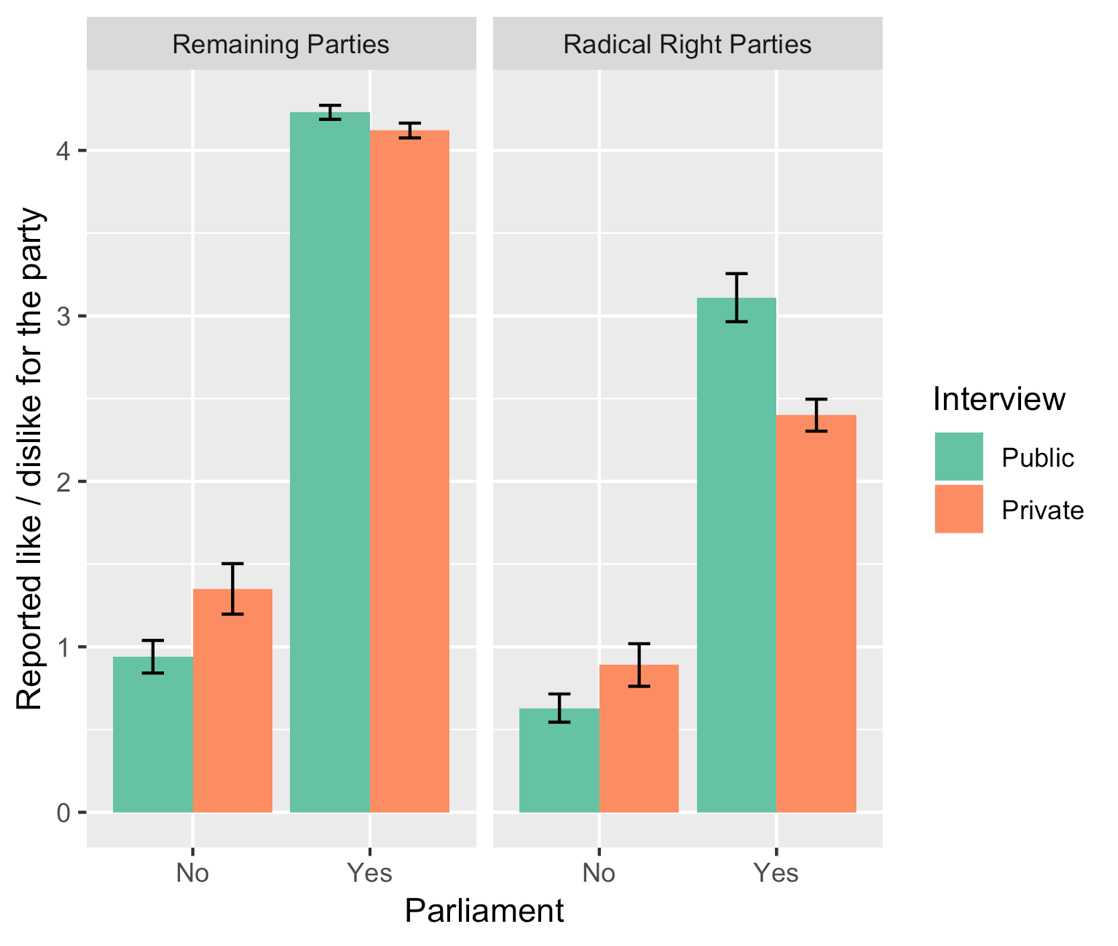

The results are shown in Figure 2 below, which shows how much individuals report to like each radical right party and the remaining parties on a scale from 0 to 10, depending on their mode of interview and on whether the party is in parliament. As expected, individuals report to like radical right parties less than the remaining parties; to like parties which are in parliament more; and to report liking parties more when the mode of interview is private. The difference between how much individuals like parties in private and public modes of interview is reduced when the parties make it to the parliament, but this reduction is larger in the case of radical right parties. In fact, when radical right parties are in parliament, individuals report to like them more in public modes of interview than in private ones.

Figure 2: Reported support for political parties present within national parliaments by type of interview conducted

Note: For more information see the author’s accompanying paper.

In the third and last study, I test whether these findings can be replicated by looking at a single party before and after it made it to parliament. To do this, I use the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP), which unlike most radical right parties considered above, ran for several elections before entering parliament. I rely once more on the proportion of the official vote for the party that is reported in post-electoral surveys and compare its evolution before and after entering parliament to that of the main parties in the UK. The results are consistent with those of the previous study. For every ten individuals that voted for UKIP, two more were willing to say they did so after the party entered parliament in 2015.

What conclusions can we draw from these findings? Two different interpretations are possible. On the one hand, it could be argued that this effect is positive for the quality of democracy, as individuals with radical right preferences are more comfortable in expressing their true preferences. On the other hand, the findings can be regarded as worrisome because these preferences often run contrary to core democratic values such as the inclusion of underprivileged groups. While further research is needed to fully understand what the behavioural consequences of the normalisation of radical right parties are, one could speculate it also makes individuals more likely to engage in other kinds of socially sanctioned behaviour, such as xenophobic or racist acts.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: vfutscher (CC BY-NC 2.0)

_________________________________

Vicente Valentim – European University Institute

Vicente Valentim – European University Institute

Vicente Valentim is a PhD candidate at the European University Institute. His research interests include voting behaviour, political parties, and protest politics. He is on Twitter @ValentimVicente