There is a significant difference in opinion on Brexit between different age groups in the UK, with older citizens generally exhibiting more negative attitudes toward the EU than younger citizens. But as Kieran Devine writes, while ‘over 65s’ are typically treated as a single category in opinion polls, there are substantial generational differences within this group, with those who lived through the Second World War being far more likely to oppose Brexit.

The EU was set up in response to the horrors and destruction of the Second World War. In the wake of the Brexit referendum result, it was oft repeated that the older generations were more likely to have voted for Britain to leave the European Union. This presents something of a puzzle; why would older generations, likely to have experienced the impact of the war first-hand, seek to remove Britain from an institution that has helped maintain peace in Europe for more than seven decades? Might it be that the ‘over 65s’ category, containing individuals several decades apart in age, conceals distinct generational differences amongst this group?

To address these questions, I have conducted an Age-Period-Cohort (APC) analysis using Eurobarometer survey data. APC analysis is used to ascertain if distinct generational effects are present in public opinion. Generational effects refer to the influence of environmental factors during each generation’s formative period (approximately between ages 15-25) on their long term political opinions, such as the prevailing social attitudes of the time or the occurrence of important political events. The Second World War is undoubtedly just such an event that may have deeply influenced the opinions of the generation that came of age during wartime.

This APC analysis used a longitudinal dataset of Eurobarometer surveys covering the years 1970-2017. These biannual surveys, consisting of 1,000 face-to-face interviews with members of the British public, ask respondents a range of questions, including their opinions on European integration. When controlling for a range of factors that have been identified as influencing attitudes towards integration – education, occupation, left-right position, gender, urbanisation – generational effects are confirmed in the data.

Specifically, when defining a ‘war generation’ that experienced the majority of their formative period during the Second World War, as well as a number of other more recent generations, this war generation is revealed as displaying significantly more positive views towards European integration than the immediate post-war generations. In fact, the size of this generational effect between the war and post-war generations is approximately equivalent to the same change in attitude that would be expected from a two-year reduction in education levels, a factor well known to increase Euroscepticism.

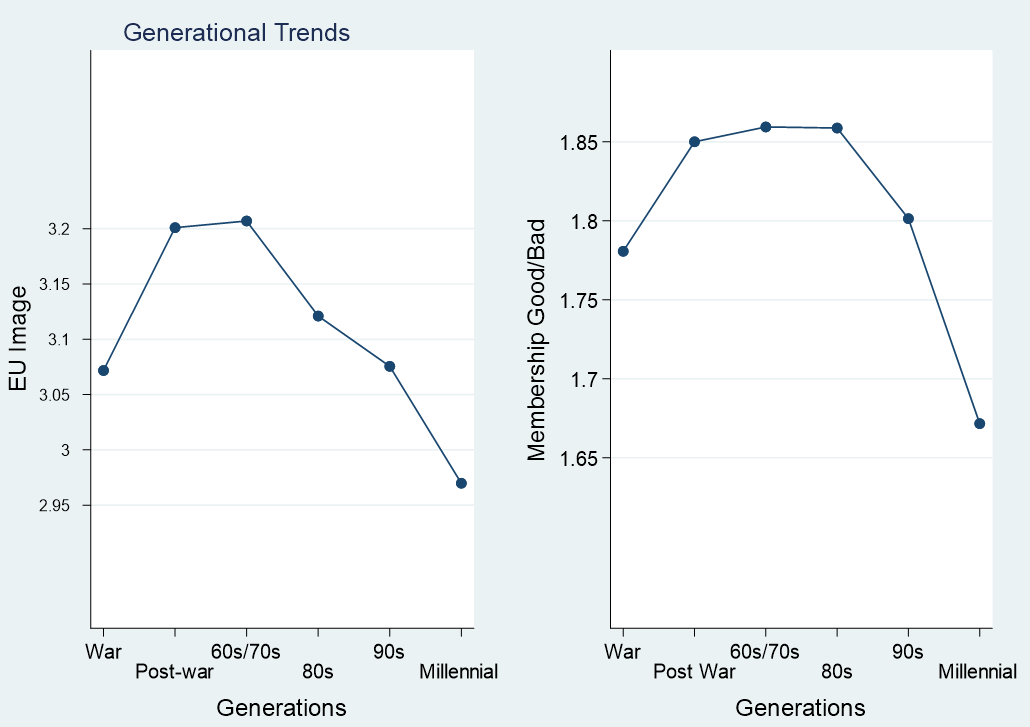

Holding all values at their mean in the data, Figure 1 illustrates the curvilinear differences in generational attitudes towards the EU in the UK. These results reflect respondents’ answers to questions regarding how positively they view the image of the EU, and whether they rate the UK’s membership of the EU as a good or a bad thing. In these illustrations, higher values connote more negative attitudes towards European integration. They therefore show that, all else being equal, the war generation have more positive attitudes towards the EU than the immediately following generations. Indeed, only the most recent generation, the millennial generation, display more positive attitudes towards the EU than the war generation.

Figure 1: Image of the EU among different generations in the UK

Note: For both charts, a higher value indicates a more negative image of the EU.

One explanation for these results is that the war generation give a premium to the pacific benefits of European institutions. Having experienced first-hand the horrors of war, they place a high value on the founding principles of unity that the EU promotes. The most recent generations also view integration more positively, given that these individuals have grown up with the UK’s membership of the EU as the norm. The concept of not being a part of Europe – with its visible signifiers of flags, anthems and institutions – is likely to be discordant to those from the millennial generation. Conversely, the post-war and 60/70s generations in the UK have neither the memories of wartime nor the routinised experiences of EU membership during their formative years. They therefore display the most hostile attitudes towards integration.

Additional variables, not captured in the Eurobarometer Survey data, appear poor alternative explanations for these findings. Reduced urbanisation, increased Protestantism, changes in party affiliation, the spread of communication technologies, and media frames have all been shown in previous research to affect attitudes towards European integration. This previous research, however, would suggest that the historical trends in these factors should lead to a reduction in hostility towards integration from the war to post-war generations. They are not, therefore, likely to be explaining the observed effects.

Including individuals’ responses to other questions in the Eurobarometer survey can more clearly outline the explanatory logics underpinning these results. Mediation analysis was performed on the answers to the question “What does the EU mean to you personally?” in the analysed models. Crucially, one of the 14 multiple choice answers to this question was “Peace”. If the observed effects were operating through the proposed ‘peace hypothesis’, accounting for those answering peace to this question should reduce the observed generational effects.

The results of this analysis confirm that this is the case: the older generations are more likely to associate the EU with bringing peace, and when mediating for these attitudes, the generational effects in the initial models are reduced by around 20%. The war generation are more likely to associate the EU with peace, and thus have more positive attitudes towards integration.

However, this analysis also reveals additional elements that are driving the cohort effects between the war and the following generations. Indeed, the post-war generation are in fact more likely to associate the EU with bringing peace than their younger counterparts, and yet they display more negative overall attitudes towards integration.

Conducting additional mediation analysis on alternative answers to the question of “EU meaning” reveals the importance of issues surrounding immigration and sovereignty to the post-war and 60s/70s generations. Almost 22% of the cohort effects are described by the post-war generation as being far more likely to associate the EU with a loss of control of the nations’ borders and a threat to national identity. Similarly, 45% is mediated by concerns surrounding a lack of the effective democratic functioning of the EU, something that has been linked in previous research to notions of an ‘anti-democratic’ EU eroding British sovereignty. It is thus not simply the scarring effects of wartime explaining the war generation’s positivity towards integration, but rather that the two following generations are also particularly hostile to European institutions.

Explanations for these results can be found in British history; the post-war and 60s/70s generations were the first to confront the fall of empire during their formative years, as well as the first mass immigration from the Commonwealth. This fuelled insecurities over British identity, coming to the fore in such instances as Enoch Powell’s “Rivers of Blood Speech” and the Immigration Acts of the 1960s. These results therefore support the notion that it is during times when identities are threatened that they become mobilised as points of political salience, and that these heightened political environments can shape individuals’ opinions long into the future.

What do these results suggest for future UK public opinion on European integration? Firstly, extolling the virtues of the pacific benefits of the EU are likely to fall on ever more deaf ears – the generation with which this argument will have its greatest impact are severely dwindling in number. Secondly, the degree to which individuals feel their British identity is threatened may govern their level of positivity towards European institutions. Thirdly, the prevailing political environment shapes the long-term opinions of those in their formative years. Given the current ubiquity of the Brexit debate, today’s arguments and events surrounding integration will almost certainly have a significant impact on the most recent generation, namely those born after the millennium. In exactly what way these debates will shape public opinion, however, remains to be seen.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics.

Thank you for your interesting article.

Growing up in the 1950s the many stories from ex-soldiers (WWI & WWII) may have left them feeling cheated not to have been ‘tested’ in battle. The anti-EU campaign conducted over many years perhaps is a substitute.

From the small sample (n=50) I encounter btl, loneliness is often a predictor of how the commenter voted in 2016. Remainers will talk about their grandchildren &/or travel; Leavers rarely mention even a partner, ruminate, one or two take pleasure when a Remainer commenter is banned, and I remember one confessing he put the radio on for company.

You confuse millennials and post millennials. Those born from the early 1980s to mid 1990s are millenials. Those born after that are post millennials.

The Figure caption for the image on the right seems to contradict the text.

Interesting. My 94 year old grandmother, who was a land girl, voted remain and is at odds with her leave voting neighbours – all in their 60s and 70s.

Walking up the road to cast my vote in Cameron’s referendum to sort out a petty squabble within the Tory Party, I was in two minds whether to Remain or Abstain because of the confusing lack of clear information either way. in the end I remained, mainly because of the confusing messages preventing a clear decision and because I spent a fruitful year working in Holland.

Subsequent events have clearly shown the great advantages of being an EU member compared with all the shenanigans of the Tory elite’s idiot explanations during this Brexit farce. In particular,their refrain of “the will of the people” is only 37% of the electorate (see Sir John Major for comment) – a minority comparable to the then existing size of the Tory vote,and where this political squabble should have been laid to rest.

TM and her minions are making such a shambolic mess of the whole process that it may eventually result in the dissolution of the Tory party for which we should all be very grateful,!

I agree and am in empathy with Jim Kent’s comment. I was in two minds whether to vote Leave or Remain right up until 2 weeks before the referendum. Although I did read the Brexit-supporting press I became increasingly sceptical of this, especially once I knew why they were so desperate for us to leave the EU: that they were owned by off-shore billionaires.

I voted Remain despite being implored by my younger sister to vote Leave. It later transpired that she had/has a Daily Mail app which is a source of most of her news – that is no coincidence!

I am 64, which seems to be a ‘typical’ age to vote Leave. But I’m relatively educated having been to University and an also very interested in classical music which ‘speaks’ an international language and iften ny European composers.

Yes, of course, in addition to squabbles within the Tory Party, Cameron was very concerned with the threat from UKIP.

Did the data for this age-related analysis come from a geographically-wide sample of the UK population, including the main regions of the UK – especially the North and North-East of England?.