It is often stated that the late-2000s financial crisis prompted a rise in both Euroscepticism and nationalism across the EU. Yet as Nick Clark and Robert Rohrschneider explain, despite evidence of a drop in support for the EU since the crisis, previous research has found the proportion of individuals identifying exclusively with the nation state has remained relatively stable. Drawing on a new study, they illustrate that the key to resolving this discrepancy lies in the relationship between national identity and EU evaluations. While Europeans may not be more nationalist overall, they increasingly turn to nationalist orientations when developing positions on the EU – a trend that predates the financial crisis.

It is often stated that the late-2000s financial crisis prompted a rise in both Euroscepticism and nationalism across the EU. Yet as Nick Clark and Robert Rohrschneider explain, despite evidence of a drop in support for the EU since the crisis, previous research has found the proportion of individuals identifying exclusively with the nation state has remained relatively stable. Drawing on a new study, they illustrate that the key to resolving this discrepancy lies in the relationship between national identity and EU evaluations. While Europeans may not be more nationalist overall, they increasingly turn to nationalist orientations when developing positions on the EU – a trend that predates the financial crisis.

The rise of right-wing populist political parties across Europe and the increase of anti-EU sentiments over the last decade have alarmed many supporters of liberal democracies. Rising support for nationalist policies, ideological polarisation within the public, and increasing Euroscepticism appear mutually reinforcing, as each of these changes may represent a rejection of the status quo and the type of centrist politics that has governed Europe over the last 60 years.

While some scholars have studied the changing patterns of nationalism and support for the EU over the last decade, few efforts consider that the rise of nationalism may predate the economic crisis. Furthermore, no study examines whether the rise in nationalism occurs primarily among ideologically right-extreme segments of publics, where one would expect it, or whether we observe a comparable rise in nationalism among ideologically moderate citizens.

In a new study, we examine the changing relationship between individuals’ national identities and their EU evaluations from 1993-2017. We not only look at the recent crises years but also the period when political integration accelerated after the Maastricht treaty came into effect in the 1990s. The most important result of our study is that the relationship between national identity and EU attitudes is about as strong for ideological moderates in 2017 as it was for ideological extremists on the right in the early 1990s.

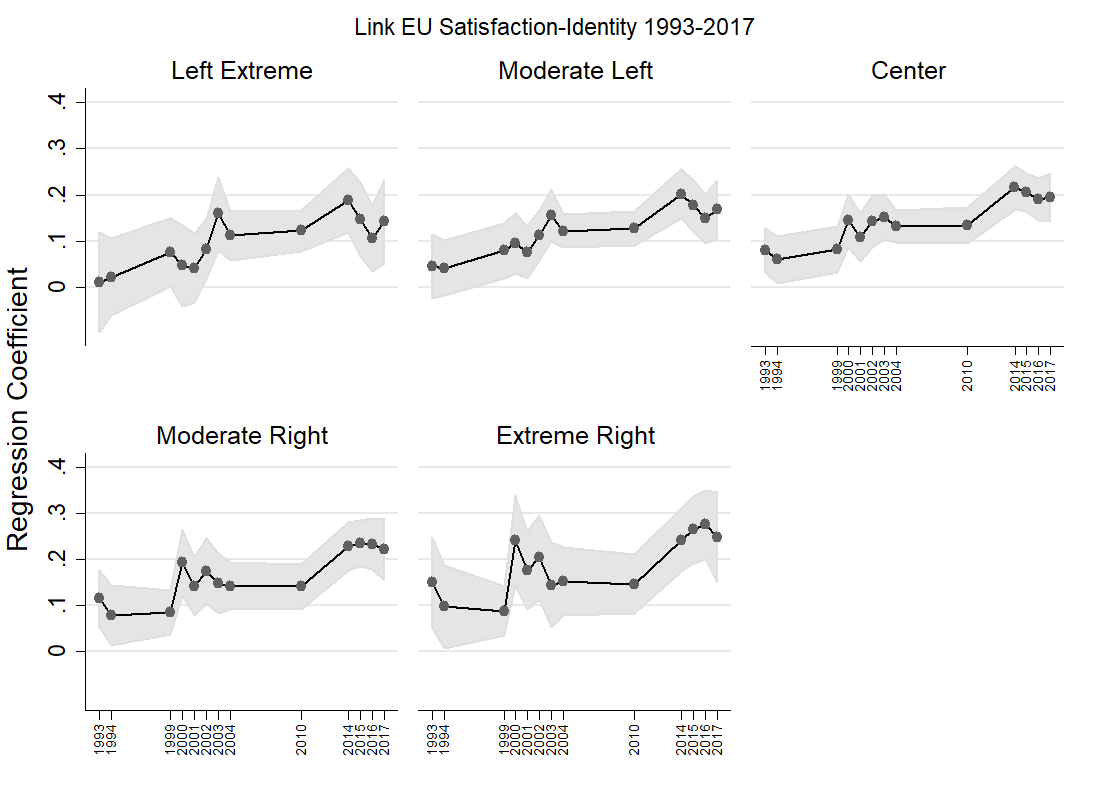

To illustrate the central finding from our study, consider Figure 1. The figure plots the influence of national identity on popular evaluations of the EU’s performance among EU member countries. The estimates reflect the relationship after we control for age, education, occupation, people’s economic expectations, and the influence of country characteristics. Each point on the ragged line represents a regression coefficient denoting the impact of nationalism on publics’ EU performance evaluations. Given our goal, we estimate the influence of nationalism on EU evaluations across years and across ideological groups. Ideological groups reflect individuals’ self-placement on an ideology scale which we recoded to range from extreme left, moderate left, centre, moderate right, and extreme right.

Figure 1: Relationship between national identity and European Union evaluations (1993–2017)

Note: Entries are regression coefficients; shaded areas are 95% confidence intervals. Satisfaction with the EU is the dependent variable. The main independent variables are the interaction between national identity, ideology, and the year of survey which constitute the basis for marginal effects. Estimation control for age, education, class, and subjective economic expectations. Country fixed effects are included in the estimation; clustered standard errors by country are estimated. Gaps on x-axis indicate that at least one variable is missing in survey year. For more information, see the authors’ accompanying study in European Union Politics. Source: Eurobarometer Representation Data set, 1993-2017

Importantly, nationalism nowadays influences a far broader swath of the European public than is commonly assumed.1 We see that the rise not only occurs for individuals with right-leaning ideological views but also for those with moderate centre-right and centre-left ideological views. This is particularly disturbing for the EU as people in the ideological centre have historically constituted the bulwark in support of integration. Clearly, individuals in the ideological centre have increasingly based their judgement about the EU on their national identity.

Why would the connection between national identity and EU evaluations strengthen over time? We see these developments arising from the growing cross-national tension over European integration. Typically, individuals develop strong affective connections with the political-territorial unit in which they reside, usually the unit recognised as the nation-state. Such connections often coincide with the demarcation of in-groups and out-groups; in other words, national identity creates the potential for intergroup conflict.

However, group boundaries alone do not trigger intergroup conflict. Such conflict occurs when and where perceived or actual competition exists over power and resources. When natural differences across groups (like nation-states) coincide with heightened competition (over the economy or migration, for example), intergroup tensions may become activated. We see the rising influence of national identity on EU evaluations as a result of the growing tension between EU member states over issues like migration and financial issues.

Furthermore, our findings suggest that national orientations began to shape support for the EU long before the crises unfolded in 2007. In fact, the temporal patterns suggest that the onset of political integration in the early 1990s stimulated the salience of national identities to the public. Several notable EU-related controversies arose in the late 1990s and early 2000s – the introduction of the euro, the Eastern Enlargement, and the EU constitution —and no doubt fortified the connection between nationalism and EU attitudes long before discussions about national debt, austerity, and migration consumed Europe. The growing magnitude of coefficients in Figure 1 and the visible bumps around 1999 and 2004 clearly support such an interpretation.

What do these findings imply? Theoretically, these findings help explain a noteworthy discrepancy in the literature on nationalism and EU support. On the one hand, several scholars find that evaluations of the EU have declined since the onset of the debt crisis. On the other hand, the proportion of individuals identifying exclusively with the nation-state has remained relatively stable in that same period. Our results confirm that while European publics may not be more nationalist on the whole, they increasingly turn to nationalist orientations when developing positions on the EU. Thus, the long-term strengthening of the relationship between these two variables helps explain why EU evaluations have become more negative over time despite relatively stable levels of national identity.

Politically, the rising link between national identity and EU evaluations does not bode well for the relationship between EU institutions and European citizens. The link increases the resilience of Euroscepticism, which is ever more anchored within national identities and not just a momentary impulse in response to negative events tied to a current crisis. Moreover, because the relationship between national identity and EU attitudes has become stronger for individuals with moderate as well as extreme ideological orientations, criticisms of the EU articulated by extreme right and left parties may resonate increasingly with citizens in the ideological centre. This no doubt will stimulate resistance to Macron’s plan to further integrate Europe. Perhaps the greatest danger for the current malaise of the EU is that the rise in salience of national identity affords EU-critical parties with growing opportunities to attract voters with moderate ideological orientations.

1. We also find that the same patterns emerge for a “trust-in-the-EU” indicator; and for a national-attachment indicator. In other words, the results do not depend on a specific measure for either EU evaluations or national identity.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying study in European Union Politics

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: CC BY 4.0: © European Union 2019 – Source: EP

_________________________________

Nick Clark – Susquehanna University

Nick Clark – Susquehanna University

Nick Clark is Associate Professor of Political Science at Susquehanna University. His research on voting behaviour and public opinion has been published in the Journal of Common Market Studies, Political Studies, European Union Politics, and the Journal of Elections, Public Opinion, and Parties.

Robert Rohrschneider – University of Kansas

Robert Rohrschneider – University of Kansas

Robert Rohrschneider is Sir Robert Worcester Distinguished Professor of International Public Opinion Research at the University of Kansas. He is currently completing an Oxford Handbook of Political Representation in Liberal Democracies (with Jacques Thomassen). With Stephen Whitefield, he is also working on a new book about representation-through-parties based on a new expert survey about party stances in Europe in 2019.