A significant percentage of greenhouse gas emissions stem from agriculture, but many national climate policies still overlook the agricultural sector. Drawing on a new study, Nicole M. Schmidt shows that while mentions of agriculture in national climate policies are growing, particularly in the EU and Africa, there remains a highly fragmented picture globally, with over half the policy documents analysed making no mention of agriculture at all.

A significant percentage of greenhouse gas emissions stem from agriculture, but many national climate policies still overlook the agricultural sector. Drawing on a new study, Nicole M. Schmidt shows that while mentions of agriculture in national climate policies are growing, particularly in the EU and Africa, there remains a highly fragmented picture globally, with over half the policy documents analysed making no mention of agriculture at all.

The ambitious goal of the Paris Agreement to limit global temperature increase to well below 2 degrees Celsius means that climate efforts in all sectors are now moving to the spotlight. Agriculture is no exception. In recent years, we have indeed seen that the established agricultural sector is ‘opening up’ and becoming more multidimensional, for instance, by integrating environmental concerns into agricultural policies. The question is whether such developments are also visible in the comparatively new climate policy domain.

Emissions from the agricultural sector are significant and rising. However, agriculture and climate change are two issue areas that, when placed in connection to each other, can quickly become a provocative subject matter. Many developing or meat-exporting countries oppose additional mitigation burdens and prioritise adaptation efforts. They recognise the sector’s contribution to climate change, but emphasise the vital role it plays in providing food, livelihoods and income, while stressing the sector’s vulnerability to the impacts of climate change. Empirically, it is also very difficult to get a sense of the extent to which agriculture is displayed in climate policies because databases do not show it separately – either they focus on energy aspects only or sum it up under adaptation or land-use and land-use change and forestry categories.

This is why I decided to build a separate database: a unique, large-n database, which allows for systematic and comparative assessments of the agricultural content of national-level climate policies. By providing a global perspective and by analysing climate policies from 1990 to 2017, I investigated the amount of agriculture and food mentions in climate policies in order to see whether these have been playing an increasingly important role in climate policies. At the same time, I was also interested in the institutions responsible for developing and issuing these policies. Because environmental ministries are usually responsible for climate policymaking, I wanted to explore coordination efforts, in particular the extent to which ministries of agriculture are involved in formulating and adopting climate policies.

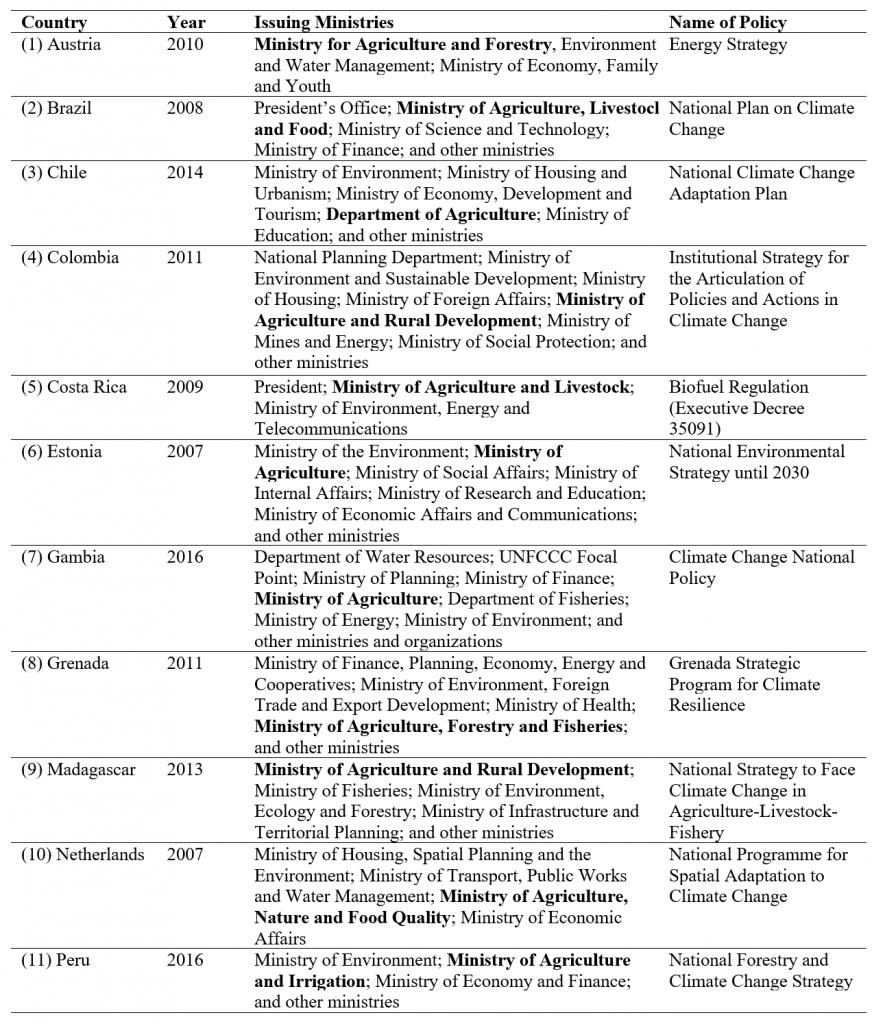

It turns out (see the table below), that out of more than 1,000 policies worldwide, agricultural and environmental ministries issued not even a dozen climate policies together. In my accompanying study, I show how little agricultural ministries are involved in the issuing of climate policies and that coordination efforts primarily concern broad national climate strategies – which typically also include other ministries. The expert interviews’ accounts with which I complemented my analysis, described agricultural ministries as politically powerful, and the independent and privileged status makes cross-sector integration and coordination efforts extremely challenging.

Table: Overview of agricultural ministries’ coordination efforts in executive climate policies

Source: Author illustration based on agri_climate database. For more information, see the author’s accompanying article in the Journal of European Public Policy.

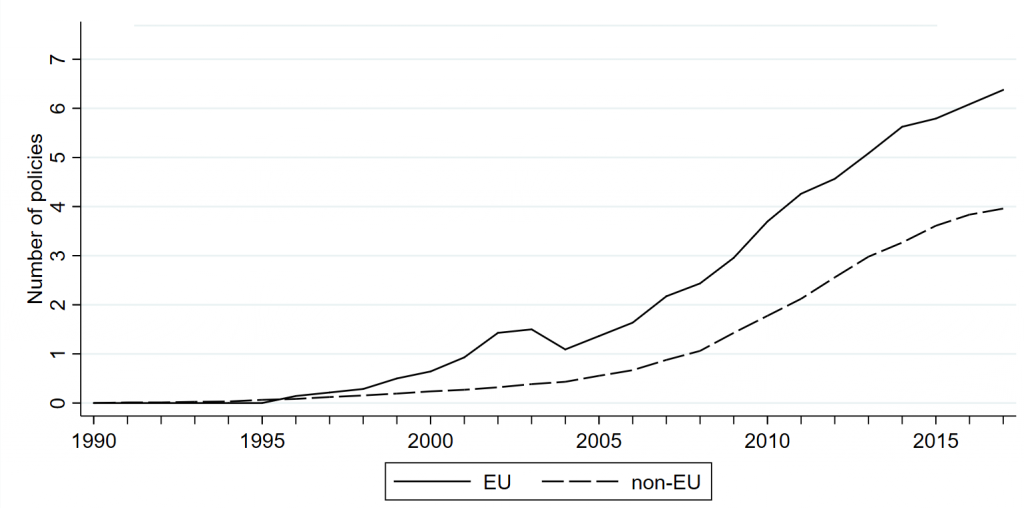

However, agri-food mentions are certainly increasingly on the policy agenda. Of 1,049 climate policies, 47 per cent had both ‘agri’ and ‘food’ mentions. On average, such policies have been increasing over time as the figure below shows. The two ascending curves vividly illustrate how the stocks of the respective policies have risen in both EU and non-EU groups. While this pattern applies to both groups, a clear difference exists in level as, right from the beginning, EU countries were the more active group in terms of mentioning agriculture and/or food in their climate policies. The accelerated growth phase is especially visible from 2005 onwards, after a modest rise starting in the mid-1990s.

Figure: Average number of climate policies with agriculture and/or food mentions per country over time

Note: For more information, see the author’s accompanying article in the Journal of European Public Policy.

So what took agriculture so long? Truth be told, agriculture is by no means a new topic in climate change politics. According to the conducted interviews, it was a topic early on in international climate negotiations. However, parties adopted a decision only in 2017 officially acknowledging the significance of the agriculture sector and working towards ways of addressing adaptation and mitigation options.

Indeed, the integration of agricultural and food components in national climate policies is not straightforward. I have identified several factors which explain the lengthy and extensive challenges around agricultural policy integration. Besides the politically powerful agricultural ministries and limited coordination efforts between ministries, these include a myriad of technical difficulties, the historically strong connection between political parties and farmers, the countries’ varying importance of the sector, and the fact that agriculture is not as intuitively connected to emissions as the energy or transport sectors.

These circumstances can therefore also explain why – even as agriculture is playing an increasingly important role in climate policies – we do not see it mentioned in a little more than half of the climate policy data I examined. On the one hand, the climate policy domain is becoming more multidimensional, which means it is a trend not only observable in established policy sectors such as agriculture, but one that is observable in new ones, too. On the other hand, climate policymaking is a task still predominantly carried out by environmental or energy ministries.

The fragmented picture suggests that ministries of agriculture and ministries of environment have, thus far, been unable to cooperate effectively with each other. This leaves room for both domains to continue to co-exist rather than to merge into an entity. Increasing the involvement of agricultural ministries and the desirability of coordination across sectors, is therefore key to the meaningful achievement of agri-climate objectives. Otherwise, we may have better and more integrated policies, but those may only have symbolic meaning or point to political intentions rather than being substantive policies anchored across relevant institutions.

For more information, see the author’s accompanying article in the Journal of European Public Policy

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Don DeBold (CC BY 2.0)

_________________________________

Nicole M. Schmidt – Heidelberg University

Nicole M. Schmidt – Heidelberg University

Nicole M. Schmidt is a PhD Candidate at the Faculty of Economics and Social Sciences at Heidelberg University, Germany. Her main research interests lie in the field of comparative EU and global climate change policy, with a focus on adaptation and public administration. She has published her research in some of the leading journals in the field, such as Journal of European Public Policy, Global Environmental Change, Environmental Science & Policy, and Review of Policy Research.