The European Parliament is often portrayed as being one of the main losers from the EU’s response to the European debt crisis. Observers have argued that the Parliament struggled to exert influence over the EU’s crisis resolution as the preparation of key legislation largely took place without its involvement. Yet, Maja Kluger Dionigi and Christel Koop show that the Parliament did not leave the negotiations empty-handed as it managed to increase its oversight powers in the reformed European Monetary Union.

The European Parliament is often portrayed as being one of the main losers from the EU’s response to the European debt crisis. Observers have argued that the Parliament struggled to exert influence over the EU’s crisis resolution as the preparation of key legislation largely took place without its involvement. Yet, Maja Kluger Dionigi and Christel Koop show that the Parliament did not leave the negotiations empty-handed as it managed to increase its oversight powers in the reformed European Monetary Union.

The European debt crisis that started off in 2009 led to one of the most challenging periods for decision-making in the European Union (EU). The EU’s response to the crisis was characterised by a rise in executive powers to the detriment of the European Parliament (EP).

The European Council largely set the agenda during the crisis, for instance by establishing the Six-Pack, the Fiscal Compact, and the European Stability Mechanism. It also played a central role in areas where EU-level fiscal capacity was required. The European Commission saw its supervisory powers grow in areas of policy coordination such as the excessive deficit procedure and the macro-economic imbalance procedure.

The EP, on the other hand, was absent from key decision-making moments and struggled to influence the overall reform doctrine and the details of legislation. It was trapped in the role it had before the 2009 Lisbon Treaty, when it was only consulted on matters related to the European Monetary Union (EMU). The expectation that the EP’s new status – as co-legislator in economic and fiscal policy with the Lisbon Treaty – would change the nature of economic governance was largely dashed.

The EP’s calls for a greater emphasis on the social dimension of the EMU largely fell flat. These included calls to introduce Eurobonds and include employment and social rights as important aspects of the EMU. The EP was also excluded from the preparation of the Six-Pack and Two-Pack, even though these were the first pieces of legislation where Parliament formally had co-decision powers. The preparation of the Six-Pack took place in the European Council-led taskforce on economic governance, not including Parliament. The Commission’s proposal on the package reflected the agreement reached in the taskforce, giving the EP limited influence over the substance of the package.

The crisis highlighted that co-decision has its own dynamics when it touches on core state powers such as migration and economic and fiscal policy. Under these conditions, the EP tends to be given a subordinate role in favour of member state action. Critics have warned that the new system of economic governance risks further eroding the already fragile democratic legitimacy of the EU because it lacks representative credentials in the absence of full-fledged parliamentary involvement.

Increased oversight powers

Yet, the EP has not been an idle bystander to its dwindling substantive powers. It fought back and managed to increase its oversight powers over the Commission, Council, and European Council in legislation addressing the crisis.

The EP successfully pushed for the creation of the economic dialogue, which allows for debates with EU top officials and finance ministers who are asked to report on, and explain, their decisions in the context of the reinforced Stability and Growth Pact. The EP also gained the banking dialogue, which requires the ECB to appear before the EP’s economic and monetary committee.

More generally, the EP has been particularly successful in negotiating greater oversight powers over executive bodies in legislation addressing the European debt crisis. Comparing crisis legislation to other economic and financial legislation negotiated between 2009 and 2016, we find that significantly more accountability provisions are added to crisis legislation.

The crisis legislation contains a range of accountability provisions, some of which are more widespread than others. They include provisions requiring the Commission to send the EP information on request, parliamentary hearings with member states, the Commission, and the (European) Council, and provisions asking these bodies to report to the EP on their activities and policy positions. They all require the provision of information and explanation to the EP, but do not grant Parliament any formal sanctioning powers.

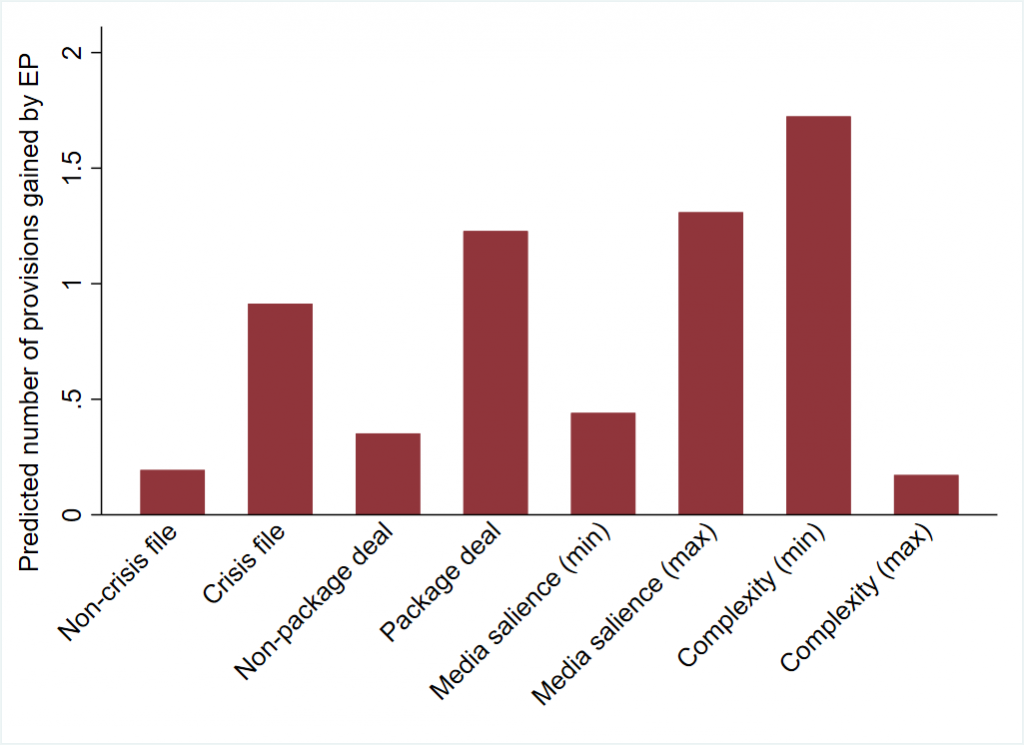

Figure 1 shows the predicted number of accountability provisions gained by the EP during the legislative negotiations. It includes both the minimum and the maximum values of the explanatory variables in our analysis. The analysis was run on a dataset of 76 legislative files in the field of economic and financial affairs, dealt with by the EP between 2009 and 2016.

Figure 1: Predicted number of accountability provisions gained (Poisson model)

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying article in West European Politics

The figure indicates that the negotiations always offered Parliament an opportunity to gain account-holding powers, but that it was particularly successful in securing such powers in crisis legislation. In addition, the EP acquired more accountability provisions in negotiations on legislative files that were part of a package deal (as compared to individually negotiated files), files that were more domestically salient, and files that were less technically complex.

The EP as ‘accountability entrepreneur’

Our findings suggest that the EP has at least partially been compensated for its loss of substantive influence on crisis legislation. Two features of the EU’s crisis legislation are likely to have given Parliament ammunition to push for more oversight powers.

First, the enhanced discretion and powers delegated to executive bodies in crisis legislation increased the risk of shirking and misuse of powers. Second, the European debt crisis exposed serious deficiencies in the EMU, in particular, vulnerabilities in its output legitimacy. Both features are associated with calls for more procedural accountability. They provided the EP – as an accountability entrepreneur – with a window of opportunity to increase its account-holding powers.

This raises the expectation that the EP might be able to reclaim lost powers when international agreements decided outside the EU’s legal framework get integrated in the EU Treaties in the future. Moreover, the increase in accountability provisions in crisis legislation is reassuring from the perspective of democratic legitimacy.

However, the EP’s account-holding powers do not normally include possibilities to sanction the account-givers. To the extent that informal sanctions, such as naming and shaming, are inconsequential, the implication is that the implementation of crisis legislation can still be regarded as largely executive-dominated.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying article in West European Politics

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. The research project was supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 649484). Featured image credit: CC-BY-4.0: © European Union 2019 – Source: EP

_________________________________

Maja Kluger Dionigi – Think Tank Europa / University of Copenhagen

Maja Kluger Dionigi – Think Tank Europa / University of Copenhagen

Maja Kluger Dionigi is Senior Researcher at Think Tank Europa and External Lecturer at the Universities of Bonn and Copenhagen. Her research focuses on legislative politics in the EU, lobbying, and transparency and accountability in EU decision-making.

Christel Koop – King’s College London

Christel Koop – King’s College London

Christel Koop is Senior Lecturer in Political Economy at King’s College London. Her research focuses on the insulation of policy making from politics and the electoral process, both at the national and European level, and including questions of democratic legitimacy, accountability, and transparency.