Switzerland will hold federal elections on 20 October. Sean Mueller explains that the vote will once again demonstrate the high level of stability that exists within the Swiss party system.

Switzerland will hold federal elections on 20 October. Sean Mueller explains that the vote will once again demonstrate the high level of stability that exists within the Swiss party system.

You may be forgiven for not knowing what happens on 20 October, for not much will in fact happen. The Swiss will vote for a new parliament, yes, and a few weeks later this new parliament will elect a new government. Given that neither parliament nor government can be dissolved or dismissed ahead of schedule, the members of both can stay in office until autumn 2023. But while such security of tenure could raise the stakes, the stability of the party system and other factors lower them. For neither is representative democracy the only game nor are parties the only players in town.

What’s at stake?

Elections are taking place for all 200 seats in the National Council, the lower or “popular” chamber, and for 45 of the 46 seats in the Council of States, the upper or “federal” chamber. The 26 cantons form the constituencies for both elections, with seats allocated in proportion to population for the one but equally for the other. Elections for the 200 National Council seats take place through a list proportional representation system, except in the six smallest cantons with only one seat. In 24 cantons, those for the Council of States take place using simple majority rules; if a second round is needed, plurality suffices. Two cantons elect their Councillors of State using proportionality. One canton has already appointed its delegate in April, at its annual citizen assembly (the six former half-cantons have only one seat; all others two).

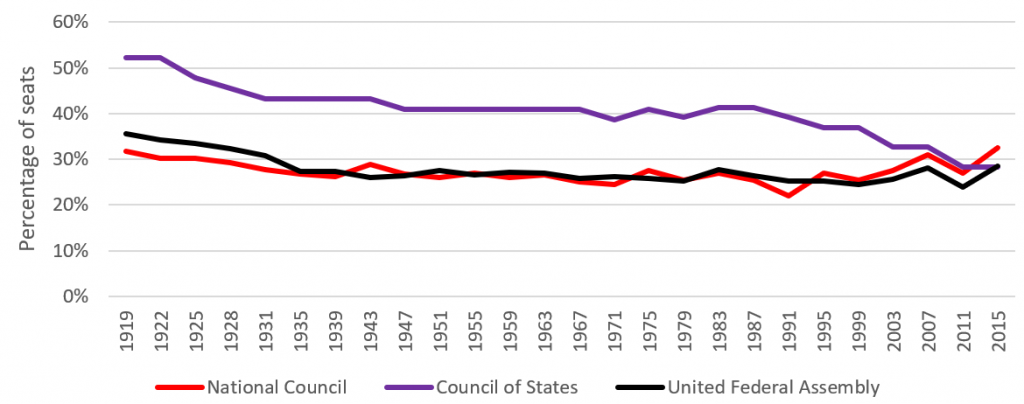

Given the equal democratic legitimacy of the two houses of parliament and their largely symmetric powers, obtaining majorities in either or even both could be thought to be very important. Which it is, but only to some extent. For while in December 2019 the two chambers will sit jointly as the United Federal Assembly to elect the seven members of the Swiss government, no party alone has ever held an absolute majority of seats since list PR was introduced 100 years ago (Figure 1). Nor is one expected to this time.

Figure 1: Percentage of seats held by the largest party in Switzerland (1919-2015)

Source: BFS (2019)

Expectations

Todays’s largest party, the national-conservative SVP (2015: 30% of the vote; 33% of seats in the National Council), is expected to lose support but remain first. While four years ago it profited from the salience of its core topics, migration and EU integration, the currently dominating issues, climate and gender equality, favour other parties. Two of them are thus expected to gain: the Greens, founded in 1983, and the Green-Liberals, created as recently as 2007. Or at least this is what various polls and elections at cantonal level earlier this year suggest.

Of the other main parties, the social-democratic SPS is predicted to hold on to second-place (2015: 19% of the vote; 22% of seats in the National Council). The liberal FDP, the only party in the world to look back on over 170 years of uninterrupted government presence (Figure 2), is expected to either gain support or lose slightly. The Christian-democratic CVP, the fourth and most junior member of government, is expected to continue losing support.

Figure 2: Parties of government in Switzerland (1848-2019)

Source: Vatter (2018) and author’s own updates

Mitigating factors

The party-political composition of government is not expected to change. Also, all of the anticipated changes in vote and seat shares are modest at best. The greatest predicted increase (for the Greens) amounts to +3.4%; the greatest loss (for the SVP) to -2.6%. Hardly landslide dimensions. And this just for the National Council, where shifts in voter preferences more quickly translate into actual seat differences – or not, given the possibility of list apparentements. The Council of States, for which predictions are harder to make due to cantonal embeddedness and strong dependence on the persons actually standing, is unlikely to change much.

Rather than parties, the more interesting factor to look out for are changes in the number of women elected, given the massive success of the country-wide Frauenstreik (women’s strike) back in June 2019. With 32% in the National Council and 15% in the Council of States – but 43% in the federal executive – there is room for growth. Looking at all the lists submitted, the share of female candidates has increased by 6% to reach a record 40%.

Some of the reasons for the slow evolution towards political parity and for the stability of the party system are identical. Next to a generally rather conservative society, standing for elections and voting for parties and persons is important, but all major policy decisions are subject to a binding popular vote anyway. Referendums are not only more frequent, occurring four times a year on average, but also more open in their outcome and thus more interesting. If even the largest government and parliament majority can regularly be overruled, why bother?

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Sean Mueller – University of Bern

Sean Mueller – University of Bern

Sean Mueller is Senior Lecturer in Swiss and Comparative Politics at the University of Bern.