The far-right party Vox is expected to see a sharp increase in support in the Spanish general election on Sunday. Mariana S. Mendes writes that the party has clearly benefited from the heightened attention paid to Catalan independence in recent weeks, but it has also managed to successfully instrumentalise the issue of irregular migration, despite a fall in the number of migrants reaching Spain by sea.

The far-right party Vox is expected to see a sharp increase in support in the Spanish general election on Sunday. Mariana S. Mendes writes that the party has clearly benefited from the heightened attention paid to Catalan independence in recent weeks, but it has also managed to successfully instrumentalise the issue of irregular migration, despite a fall in the number of migrants reaching Spain by sea.

Spain is headed for new elections this Sunday, the fourth in four years and the second this year alone. The failure of the country’s main centre-left party (PSOE) to secure parliamentary support for forming a government was both a result of political fragmentation as well as of its own incapacity to adapt to a new scenario where coalition-forming dynamics should be taken seriously.

Months of talks with the left-wing Unidas Podemos (UP) came to a dead end in September, after much disagreement and clumsy negotiations over the form the new government would take and how large a role UP would play. The price to pay is another round of elections whose results might well prolong the political impasse, to the exasperation of voters whose (justified) fatigue could negatively impact on turnout.

But if polls do not predict significant inter-bloc volatility – in a scenario where the left and right bloc are almost equally divided with about 43% of the vote – intra-bloc volatility is expected. On the one hand, the landscape is even more fragmented now, with a new option on the left – Más País – resulting from a defection from Podemos. Since fragmentation impacts the conversion of votes into seats, this is bad news for the left.

On the other hand, the radical right Vox party is set to make further gains, possibly growing into the third largest party in parliament, to the detriment of Ciudadanos (a party whose oscillation between the centre and right is not pleasing voters). This is extraordinary for a party that was barely known a year ago. After its success in the Andalusian local elections of December 2018, Vox obtained 24 seats in the April 2019 general elections (10% of the vote). Polls are unanimous in predicting its growth this Sunday, estimating that Vox might capture more than 40 parliamentary seats.

Its staunchly nationalist agenda has most obviously profited from the Catalan independence challenge and the subsequent backlash among large sections of the Spanish population who are opposed to separatism. Part of Vox’s recent boost in the polls is explained by the centrality of the Catalan issue, after a month of (sometimes violent) protests and civil unrest in Catalonia, following the recent jail sentences of nine separatist politicians for their involvement in the 2017 independence referendum. One in every four voters admitted in April that the Catalan conflict had an influence over their vote and Vox was the party that benefited most from this (excluding pro-independence parties).

Vox has the toughest stance on the issue, proposing the suspension of Catalonia’s autonomy, the criminalisation of separatist parties and organisations, and severe prison sentences for their leaders. It has also been the first party in parliament to advocate a complete recentralisation of the state. Though the majority of Spaniards (about 40%) support the current model of territorial organisation, it is noteworthy that Vox has filled a gap in the representation of those who would prefer a centralised state – a percentage that has oscillated between 12 and almost 25% of the population in the last ten years.

The Catalan issue and the territorial organisation of the state are, however, far from the only issues on which Vox has tried to capitalise on. The party presents itself as a ‘patriotic alternative’ to the ‘progressive dictatorship’ (pejoratively called ‘dictadura progre’) on themes like immigration, feminism (‘gender ideology’) or historical memory. Though it has a liberal position on economic matters, it seems to be learning fast from its European counterparts, recently showing a protectionist face against ‘global elites’. In a clear replication of the populist exclusionary discourse that has proliferated in other parts of Europe, its defence of sovereignty and borders is linked to irregular immigration, a theme that Vox has tried to exploit to an extent that has not been seen in Spanish politics before.

A cursory look at its recent social media activity shows that, together with Catalonia and separatism, immigration is indeed the issue the party is now most focused on. This was obvious in the prime-time debate that took place on Monday (the only one that gathered the main party leaders), when Vox’s leader, Santiago Abascal, repeatedly brought the issue to the fore, openly associating illegal immigration with crime, gang rape cases, and public spending, and going as far as to speak of an EU-led ‘Islamisation’ of Europe.

Abascal did not shy away from using a demagogical zero-sum-game logic, making a direct link between social assistance benefits to immigrants and the lack thereof to Spanish nationals, or from employing inaccurate figures, such as stating that 70% of gang rapes are committed by foreigners (statistics that the Spanish press were quick to pick apart). Though the other candidates might have their own reasons to stay silent on these issues, it is doubtful whether their ‘dismissive strategy’ was a smart move in a setting where almost nine million viewers were watching at home.

Even though Spain is often praised for its migration-friendly attitude, Vox is evidently trying to appeal to the minority who view immigration with suspicion – in 2018, 22% of Spaniards thought the impact of immigration on society was entirely negative, in contrast to 16% in the UK and the Netherlands. Even if the politicisation of the topic might have little impact on changing often resilient attitudes, it can activate preferences and boost the importance of the issue in the eyes of voters. It is worth noting that the public salience of immigration has increased over the last year, with about 15% of respondents placing it among Spain’s top three concerns in September 2019 (above the percentage of those who considered Catalan independence a top problem).

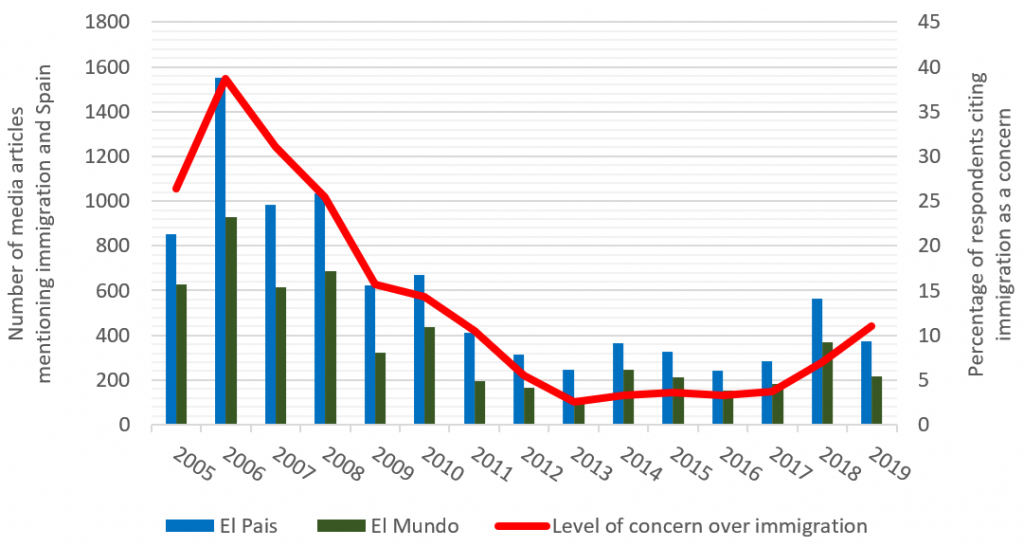

As demonstrated elsewhere, concerns over immigration tend to go hand-in-hand with media attention paid to the issue (Figure 1), which is in turn not independent from the substantial variation in the number of migrants who attempt to reach Spain every year (Figure 2). This was visible in 2006 – when Spain experienced its first migratory crisis due to an upsurge in the number of boats reaching the Canary Islands – and to a lesser extent last year, when Italy’s decision to close down its ports redirected migratory routes to the Iberian peninsula in the summer of 2018, with Spain registering a sharp increase in the number of arrivals.

Figure 1: Media attention paid to immigration and public concern over immigration (2005-2019)

Note: The figures on the right refer to the percentage of people in Spain who mention immigration as one of their top three concerns (CIS). The figures on the left refer to the number of news articles in two major Spanish newspapers (the centre-left oriented El País, and the centre-right oriented El Mundo) which contained the words ‘immigration’ and ‘Spain’.

Figure 2: Number of irregular arrivals reaching Spain via the sea

Source: Ministry of the Interior

Even though there was a substantial reduction in both media attention and the arrival of migrants throughout 2019 – in comparison to last year – concerns over immigration remain as high in 2019 as they were over the same period in 2018. This is most likely the result of Vox’s instrumentalisation of the immigration issue, which now also drives its public salience. It remains to be seen whether the so-called integration-demarcation cleavage will become a major axis of competition in Spanish politics – in a scenario already saturated by the territorial issue – but Vox are surely trying to make it a salient one and the party’s competitors may not be able to ignore it for much longer.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Contando Estrelas (CC BY-SA 2.0)

_________________________________

Mariana S. Mendes – TU Dresden

Mariana S. Mendes – TU Dresden

Mariana S. Mendes is a Visiting Fellow at MIDEM (Mercator Forum Migration und Demokratie) at TU Dresden. She holds a PhD from the European University Institute. She tweets @MarianaSeMendes

The real story we saw wasn’t about the far right it was about extremes. When there is a crisis, people go for the extremes, not the center and Vox are just the most extreme party you can vote for today. They don’t have a real platform and will not be here for long.