The French Yellow Vests recently celebrated their first birthday, yet there remain many uncertainties about how to interpret the movement. Drawing on an online survey of 5,000 participants, Tristan Guerra, Chloé Alexandre and Frédéric Gonthier contend that economic populism is key to understanding the protesters’ grievances.

The French Yellow Vests recently celebrated their first birthday, yet there remain many uncertainties about how to interpret the movement. Drawing on an online survey of 5,000 participants, Tristan Guerra, Chloé Alexandre and Frédéric Gonthier contend that economic populism is key to understanding the protesters’ grievances.

Since November 2018, France has witnessed an unprecedented social movement. What started as an online growl about tax policy has quickly escalated into real life action from a part of French society that is usually invisible. Using the hi-vis vest as a rallying symbol, nearly 300,000 demonstrators took to the streets, hijacking the media and political agenda in the first weeks of the movement, with widespread support from the public. Although the movement has lost in intensity, diehard protesters have been marching every Saturday for 53 consecutive weeks now.

Some pundits have compared this unusual protest to the global justice movement and to the southern European anti-austerity movements that emerged in the wake of the Great Recession. Others prefer to interpret it as a consequence of a dysfunctional semi presidential system which fosters political distrust. By contrast, the populist attitudes of the Yellow Vests and their ‘producerist’ narrative have attracted less attention.

A textbook populist movement

The mobilisation first started on Facebook groups to help coordinate a mass of independent protesters and facilitate self-made communication that was bypassing the distrusted mainstream media. A year after the beginning of the movement, more than 1.7 million people are still following a Yellow Vest group. We took advantage of this momentum to conduct an online survey via 300 Facebook groups, including the major national and local groups.

We presume that this approach should not have induced much distortion. Using online social media is, indeed, a way for protestors to access key information such as the locations of demonstrations. As a result, it can be assumed that a large number of those who took to the streets were exposed to our survey. In addition, there are strong grounds to believe that those Yellow Vests who are not active on social media and those who visit Facebook groups are part of the same social environment. We also posted the link to the questionnaire at different times and days of the week.

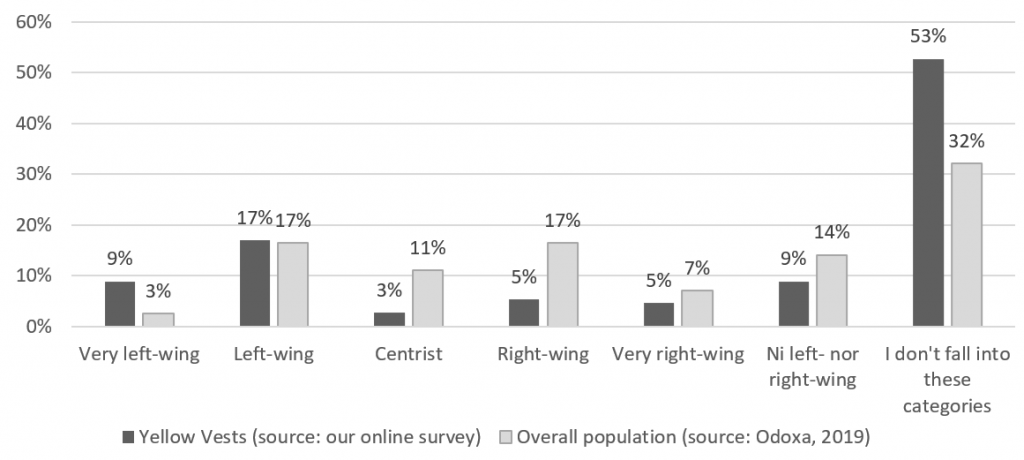

Data collected since December 2018 provide strong evidence of populist attitudes. Core populism reflects the belief in a moral conflict between the virtuous ordinary people and the corrupt elite that has usurped power for self-serving purposes. Populist attitudes have three specific features: anti-elitism, a focus on the people as a whole, and demands for the sovereignty of the people. As Figure 1 shows, the Yellow Vests check all these boxes.

Figure 1: Populist attitudes among the Yellow Vests

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying journal article in Populism.

First, their anti-elitism is straightforward. According to our study, 76 per cent strongly agree that ‘elected officials talk too much and take too little action’. And 72 per cent strongly agree that ‘the political differences between the elite and the people are larger than the differences among the people’. Mistrust of political representation and abuses of power is so strong that local groups make sure that the coordination remains as horizontal as possible and that self-designated leaders are discarded.

The demand for people’s sovereignty is also characteristic of the Yellow Vests: 78 per cent of them strongly agree that ‘politicians need to follow the will of the people’, and 62 per cent strongly agree that ‘the people and not political leaders should take the most important decisions for the country’. The government’s refusal to reinstate the solidarity tax on wealth reinforced the idea of a broken democratic system that cannot be repaired unless people take matters into their own hands. It is not surprising, therefore, that the flagship citizens’ initiative referendum (RIC) made it to the top of the list of protesters’ demands.

Finally, the Yellow Vests clearly illustrate the definition of the people as a homogeneous whole. In addition to claiming that ‘power should be returned to the people’ and that ‘the people is finally awaking’, protesters ensure their oneness by avoiding divisive topics and by focusing their actions on the vertical divide between themselves and the elites. On roundabouts, a code of good conduct has been crafted to ban extreme and partisan views that do not relate to their two shared goals: boosting ordinary people’s purchasing power and political leverage.

An economic populism driven by a producerist narrative

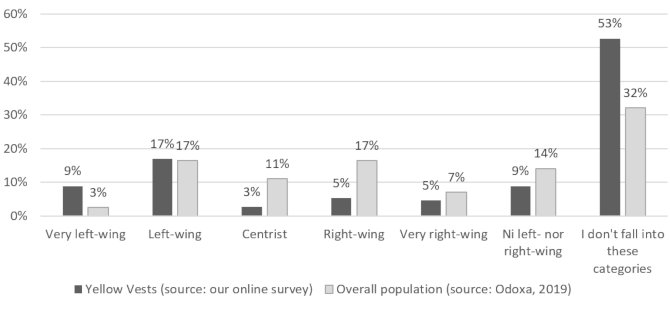

Scholars assume that populism needs to be combined with left- or right-wing ideologies, operating as exclusionary or inclusionary ways of defining ‘the people’. We found that the Yellow Vests are neither left nor right populists. As a matter of fact, most protesters are alienated from conventional politics. As evidenced by Figure 2, many of them reject the left-right labelling: 53 per cent say they ‘do not belong to the categories’ and 9 per cent that they are ‘neither left nor right’, far more than in the general population.

This largely explains why their self-categorisation as ‘the people’ is not supported by traditional working class or nativist narratives. Rather, they define themselves as the authentic community of producers of France’s wealth, hence articulating a populist economic discourse known as ‘producerism’.

Figure 2: Ideology of the Yellow Vests compared to the French population

Note: Respondents were asked where they stand politically in the above-mentioned categories. For more information, see the authors’ accompanying journal article in Populism.

The socioeconomic status of the Yellow Vests is central to the assertion that they embody the hardworking people and speak on their behalf. More than 65 per cent of them have a job but differ from the rest of the working French population by the high vulnerability of their job status. Based on a multidimensional measurement of social insecurity, 67 per cent of our sample can be considered to be in a precarious situation, almost twice the national average.

Thus, we can better understand why they feel that the tax burden is unfairly shared and why they criticise political elites for their poor management of taxation. They see themselves as the backbone of economic prosperity which is threatened by a ‘parasitic’ caste of unproductive ‘takers’. ‘They are lining their pockets from our hard-graft’ summarised one of the respondents.

However, our study highlights a point of divergence from the classic producerist narrative, which tends to lean to the right. The Yellow Vests do not, indeed, blame those from lower social strata, such as unemployed people or immigrants who are the customary scapegoats of the European radical right. Rather, they share a sort of left-wing solidarity without endorsing its inherent universalism and equalitarianism and without rejecting the whole neoliberal order.

This is why Jean-Luc Mélenchon, the leader of the French radical left, has failed to infuse the movement with an anti-austerity narrative. And why Marine Le Pen, his counterpart from the radical right, has not been successful either in permeating the Yellow Vests with an anti-migrant rhetoric.

What’s left of the Yellow Vests? One year after the start of the movement, its results are rather mixed. The difficulties encountered in fielding candidates for the European Parliament elections as well as their very weak electoral performance, indicate that the populist appeal is not enough to unite the impoverished working people behind a shared political platform. Still, although rejected by the government, their key demands such as the citizens’ initiative referendum and the solidarity tax on wealth have marked the political agenda and will most certainly be taken up by challenger parties during the 2022 presidential election.

The authors are currently conducting a research programme on the Yellow Vests movement. This post is based on a journal article published in Populism.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Tristan Guerra – Univ. Grenoble Alpes

Tristan Guerra – Univ. Grenoble Alpes

Tristan Guerra is a PhD Candidate studying Political Science in the School of Political Studies at University Grenoble Alpes, Pacte-CNRS.

–

Chloé Alexandre – Univ. Grenoble Alpes

Chloé Alexandre – Univ. Grenoble Alpes

Chloé Alexandre is a PhD Candidate studying Political Science in the School of Political Studies at University Grenoble Alpes, Pacte-CNRS.

–

Frédéric Gonthier – Univ. Grenoble Alpes

Frédéric Gonthier – Univ. Grenoble Alpes

Frédéric Gonthier is an Associate Professor of Political Science in the School of Political Studies at University Grenoble Alpes, Pacte-CNRS.