Poland experienced a sharp rise in inequality during its transition from communism to capitalism, and this trend has continued into the 2000s. Pawel Bukowski and Filip Novokmet chart a century of data on Polish inequality to examine the key causes. Their work illustrates the central role of policies and institutions in shaping long-run inequality. This rising inequality and promises to address it through redistributive policies were key factors in the victory of Law and Justice at this year’s Polish election – and they could well be a major feature in the UK’s upcoming election campaign.

Poland experienced a sharp rise in inequality during its transition from communism to capitalism, and this trend has continued into the 2000s. Pawel Bukowski and Filip Novokmet chart a century of data on Polish inequality to examine the key causes. Their work illustrates the central role of policies and institutions in shaping long-run inequality. This rising inequality and promises to address it through redistributive policies were key factors in the victory of Law and Justice at this year’s Polish election – and they could well be a major feature in the UK’s upcoming election campaign.

Poland’s profound transformation from communism to a market economy happened in less than one generation, and the accompanying economic growth has been the fastest in Europe and much faster than that of famous ‘Asian Tigers’. At the same time, however, there has been growing support for redistributive policies, which became a key factor in the election victories of the right-wing populist party Law and Justice in 2015 and 2019. A flagship family allowance programme (500+) was introduced in 2016, and the retirement age has been lowered to 60 for women and to 65 for men. In the electoral campaign of 2019, a further expansion of 500+ was proposed along with a radical increase of the minimum wage from around 46% of the average wage to nearly 78%.

This suggests that, although the real average national income has more than doubled since 1990, not all income groups and income sources have benefited from it equally. How do inequalities evolve in such quick-changing societies and what is the role of transition policies and emerging institutions? How does the Polish experience compare to western European countries, Russia, other former socialist countries in the EU, or to China and other developing countries?

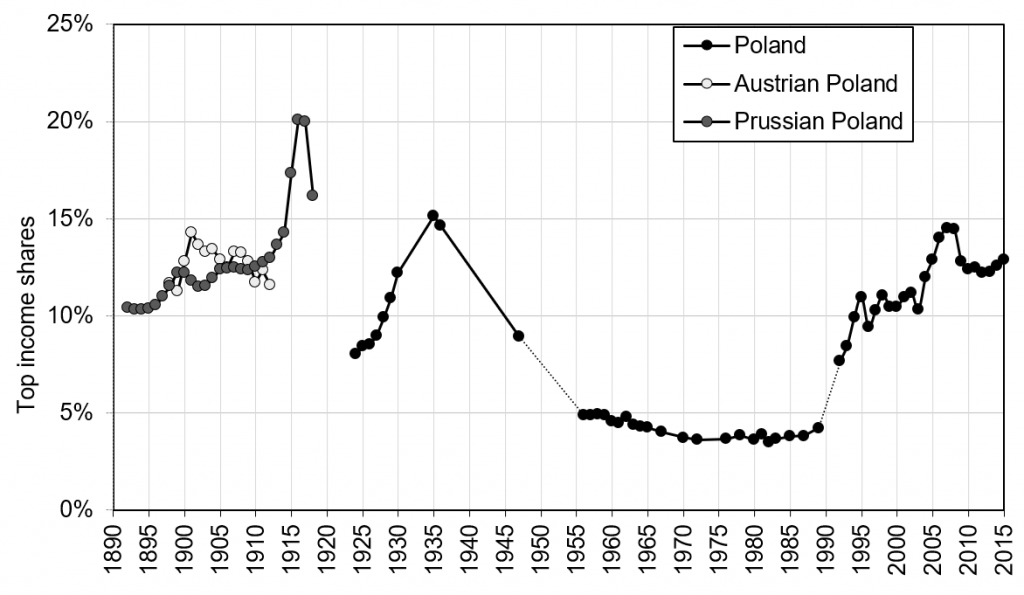

In a recent study, we made a comprehensive attempt to look at the long-run evolution of inequality in Poland. We combined tax, survey and national accounts data to provide consistent series on the long-term distribution of national income in Poland. Figure 1 shows that top income shares in Poland have followed a U-shaped evolution from 1892 until today. Inequality was high in the first half of the twentieth century due to the high concentration of capital income at the top of the distribution. As has been documented now in many countries, the downward trend after the Second World War was induced by the fall in capital income concentration.

Figure 1: Income share of the top 1% in Poland (1892-2015)

Note: the Prussian Poland is the Province of Posen and West Prussia; the Austrian Poland is Galicia. Source: Authors’ computation based on income tax statistics. Distribution of fiscal income among tax units.

The introduction of communism signified a comparatively greater shock to capital incomes relative to other countries, by literally eliminating private capital income with nationalisations and expropriations. In addition, it implied a strong reduction of top labour incomes. During the remaining four decades of communist rule, top income shares displayed notable stability at these lower levels.

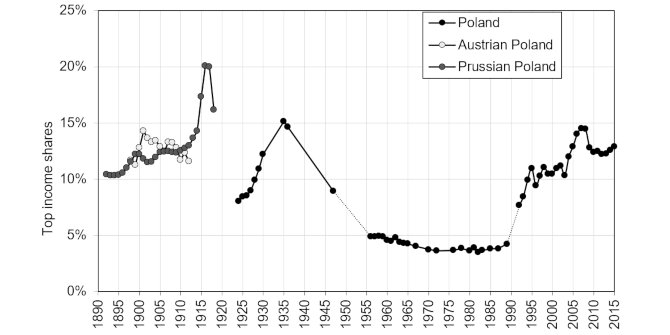

We analysed the transition from communism to the market economy by constructing the full income distribution (1983-2015) from combined tax and survey data. Figure 2 shows there was a substantial and steady rise in inequality after the fall of communism, which was driven by a sharp increase in the income shares of the top groups. Within one generation, Poland has moved from being one of the most egalitarian to one of the most unequal countries in Europe. The highest increase took place at the outset of the transition in the early 1990s, but we also found substantial growth since the early 2000s, after Poland joined the EU.

Figure 2: Income shares in Poland (1983-2015)

Source: Authors’ computation. Distribution of pre-tax national income (before taxes and transfers, except pensions and unemployment insurance) among equal-split adults.

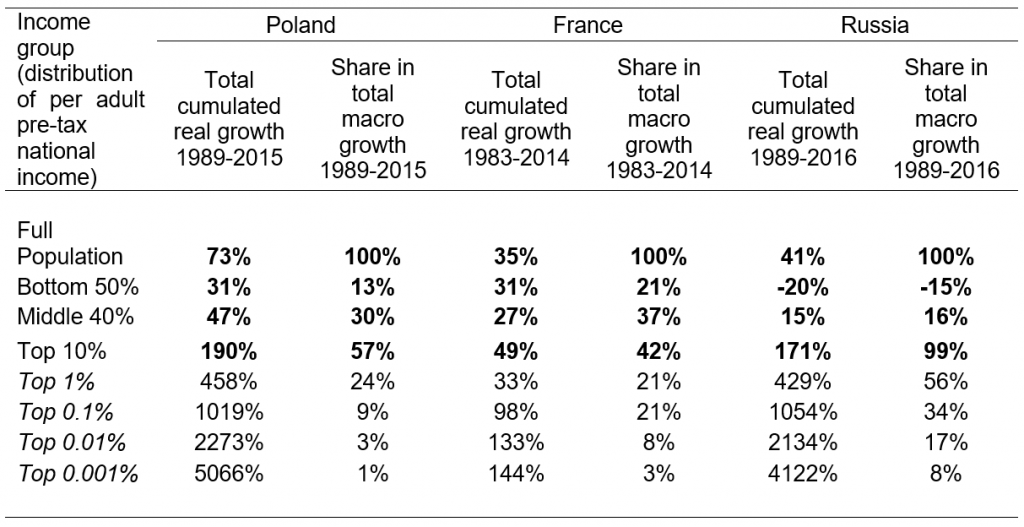

Today, Polish top income shares are at the level of more unequal European countries, most notably Germany and the UK, but still substantially below those documented in Russia. The table below shows that over the whole period 1989-2015, the top 1% has captured almost twice as large a portion of total income growth than the bottom 50% (24% versus 13%). This contrasts with France, where the top 1% captured the same share of growth as the poorest half.

Table: Income growth and inequality in Poland, France and Russia

Source: Poland: Bukowski and Novokmet, 2019; France: Garbinti et al, 2017 (Table 2b); Russia: Novokmet et al, 2018 (Table 2).

The rise of inequality after the return to capitalism in the early 1990s was induced both by the rise of top labour and capital incomes. We attribute this to labour market liberalisation and privatisation. But the strong rise in inequality in the 2000s was driven solely by the increase in top capital incomes, which are dominant sources of income for the top percentile group. We relate the rise in top capital incomes to current globalisation forces and capital-biased technological change, which have potentially rebalanced the division of national income in favour of capital.

Overall, the unique history of Polish inequality illustrates the central role of policies and institutions in shaping inequality in the long run. The communist system eliminated private capital income and compressed earnings, which led to the sharp fall and decades-long stagnation of the top income shares.

By the same token, labour market liberalisation and privatisation during the transition instantly increased inequality and brought it to the level of countries with long histories of capitalism. On the other hand, a marked increase in social transfers and expansion of the safety net during the early transition years played a key role in ‘protecting’ the bottom 50% of the distribution. It provided the general political support for market reforms and enterprise restructuring in Poland.

This contrasts with the Russian transition, as shown in the table above, where the share of the bottom 50% collapsed. Social transfer payments in Russia were small and declining, while pensions were not indexed for inflation, leading to a plunge in living standards of the bottom 50% when hyperinflation struck in the early 1990s. This suggests that mitigating a more substantial rise in inequality may be conducive to economic growth.

Finally, recent developments suggest that the future of inequality in Poland is likely to be linked with the prominent role of capital income among top incomes. Moreover, one should not expect a weakening of this trend, as processes connected with globalisation and technological change seem to contribute to the growing dominance of capital in the economy.

Rising inequality might have adverse social and political implications, as is evident in the recent populist anti-globalisation backlash in Poland and internationally. The issue of distribution of gains from economic growth has become crucial for sustaining long-run development.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying CEP Discussion Paper

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Pawel Bukowski – CEP

Pawel Bukowski – CEP

Pawel Bukowski is a Research Officer in the labour markets programme at the LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance (CEP).

–

Filip Novokmet – University of Bonn

Filip Novokmet – University of Bonn

Filip Novokmet is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the University of Bonn and World Inequality Lab.

Inequality is fine with opportunities going up. 1980s Poland was not better than today. Now the country is developing and some at the top earn a lot of money but we are still better today than before.

“marked increase in social transfers and expansion of the safety net during the early transition years played a key role in ‘protecting’ the bottom 50% of the distribution”

This is patently untrue.

No unemployment benefit to speak of at a time of high unemployment = a Victorian-style “social net”. The current left-wing government (which harks back to the pre-war Polish Socialist Party) still hasn’t introduced proper unemployment benefit, because we now have full employment.

The situation in Poland re “equality” is massively skewed by foreign ownership of the economy. The stat showing 80% of Poland’s exports being made by foreign-owned companies blows all the “equality” stats completely out of the water.

The post-1989 transformation was based on the plan of Prof Jeffrey Sachs (called the Balcerowicz Pland, after the ex-hardline Communist minister who introduced it). Sachs envisaged no property restitution – to Poles or Jews alike. This plan was sold to the Communists by Adam Michnik and Bolesław Geremek – as Sachs wrote in his book on the subject. The difference between the introduction of Sachs’ plan in Poland and the identical plan in Russia (yes, you read that correctly) is that the Russians didn’t want foreign ownership. So they transferred 50% of the economy to 7 men in 18 months. No equal opportunities there. In Poland, the markets were sold off to foreign Big Businss to set up oligopolies. When I go shopping in my local Auchan hypermarket there are almost no products from Polish-owned companies. And many of the oligopolists’ products are second-quality. Poor quality washing powder in the same wrapping as in the West.

Moreover, all growth figures pre-2015 were fake. One of the first things the Law and Justice govt did was to re-base the economic figures. In 2009 Donald Tusk proudly presented Poland as not having gone into recession. Alongside Greece – the other bastion of reliable figures!!

Meanwhile two million Poles escaped their heaven on earth, so they could actually find a job that would keep a roof over their head.

In 2014, after 24 years of “miraculous growth” official Polish govt stats showed that 400,000 children only had meat on the table twice a week. Having chidren was the leading single cause of poverty. After the introduction of child benefit (now universal) the stats on extreme child poverty improved so much that the United Nations praised Poland for its child-centred policies.

And the left-wing govt is boosting wages by raising the legal minimum wage. How can pundits drone on about them being “right-wing”? They are even supported by the main Solidarity union. Incomes have risen 16.6% in 3 years.

Polish politics – like Polish political pundits – fall into two camps: the Communist cultural camp (cheerleaded by the post-Communist media and the German-owned media) and the anti-Communist cultural camp (cheerleaded by two weekly magazines — Sieci and DoRzeczy — set up by journalists that Donald Tusk had sacked as part of his repression of free speech campaign after the assassination of the “Populist” President Lech Kaczynski in 2010. Law and Justice use public media as their mouthpiece now they are in govt. Like Tusk did previously.

The Polish political scene is in flux – Tusk’s gangster-friendly regime collapsed under its own extreme corruption ($20 billion lost to a Russian mafia fuel scam sanctioned by Donald Tusk) and use of violence (like the murder of tenants’ rights activist Jola Brzeska by a gangster protected by the police and the regime – and linked bizarrely to the murder of Helene Pastor in Monaco). The Communist cultural vote is shifting to Lewica (“Left”), which is actually left-wing (as opposed to Tusk, who was Ultra Hard Right, pro-foreign Big Business). Lewica is also unashamed of Poland’s Communist past. Tusk’s Civic Platform unwittingly prepared the ground for this dangerous state of affairs – by things like repeatedly part-blaming Poland for the Holocaust and labelling all the anti-Nazi, anti-Communist WW2 fighters as “fascists”. This is reflected in the change of street names in Warsaw – back to celebrating Old Commie heroes.

If the maths at the next election so dictates, the Far Left Lewica will naturally enter in coalition with the Ultra Hard Right Civic Platform … on the grounds of their shared Communist cultural background!! Do remember that 23 of Civic Platform’s current MPs worked as agents for the secret police in the 1980s Communist Poland.

Agree with everything you said. I would like to point that Lech Walesa as an asset of former communist secret police (involved in murder blackmail and invilgilation of polish citizens) was a puppet used to legitimize the spurious transfer of power between communists and left leaning and anticlerical anti-Polish elements of the opposition (Michnik, Geremek, Kuron) to create a postcolonial state with nepotism, corruption in every aspect of public life and oligopoly (national companies being fraudulently privatised by transferring them to former communists) and with

murder of some nonconformant politicians (Lepper) or journalists (Zietara) being a commonplace.

As a fellow Pole I can ascertain that every word of Dave is painfully true. I would like to add that first Polish “democratic” leader Lech Walesa was in fact as it was proven by independent historians an asset of infamous communist secret state police Sluzba Bezpieczenstwa involved in massacres of Polish democratic activists, priests and mass invigilation and repression of Polish people. Walesa was hand steered by communists and former agents who created oligopolic economics for themselves by fraudulent privatisation of national companies and nepotism in every major branch of public service. Poland became a postcolonial state with former communists as new “progressive” elites being pampered by Western leftist media and political pundits.

Not to dogpile on everything the previous commenters have added but one thing that strikes me is how can you compare the income inequality of any post communist country pre 1989? Even if the data is correct, society was egalitarian because nobody had anything. Sure, there is income inequality but if you look at the overall picture everyone is better off now then in 1989 by a wide margin! The “U” shape is due to the illogical economic system that was in place from 1945-1989, I’m sure if you look at the income inequality statistics of Venezuela you will also find a steep drop in inequality but that’s only because the pie has shrunk. The Polish economy has grown 5-fold in the last 30 years and most people don’t find it problematic that some make more then others when everyone is getting wealthier.

If you look at the chart here then inequality is up a lot on 2000, long after communism. The “inequality doesn’t matter if the country keeps getting richer” thing is what neoliberals say to justify low taxes and low welfare. The whole reason Law and Justice won the last two elections is because a lot of people thought they weren’t sharing in the spoils of Poland’s economic growth while a small elite was getting richer and richer. It does matter, people do care, and we’ve seen that in the last four years.

Unfortunately, all the comments above except Ham’s are full of nonsense and lies. The article is better, but it so obviously promotes a neoliberal view of the future, which is by no means assured given the trend toward redistributive policies. The PiS economic promises are now in large part supported by the Left, which will try to ensure they are enacted rather than opposed because they were introduced by PiS. Zandberg’s Left response to Morawiecki’s “speech from the throne” was a dramatic breath of fresh air compared with the sterile pro-forma opposition to everything PiS promoted by the PO’s Grzegorz Schetyna (whose days as opposition leader are numbered). Poland needs to change its taxation policies to more like those of Canada, for example.

Given how income had significantly less impact on living standards under communism as opposed to party connections one can argue that this is comparison is flawed.

The implications are also important to consider. If non-democratic states can yield a more egalitarian society than democratic ones, then why should we care about democracy?

Very interesting comments. As a foreigner visiting Poland for the last 15 years on a regular basis, the economic growth and weath generation has been outstanding. I wholeheartedly hope that education at all levels of society will continue to improve, and HONEST judges, and RESPONSIBLE politicians will deliver the well deserved prosperity that the Polish population should have reached long time ago.