Polling data suggests that Brexit is viewed as the most important issue for voters ahead of the UK’s general election on 12 December. Immigration, which has previously been viewed as one of the most important issues, has experienced a relative decline in salience since the last general election in 2017, but its purported effects on the labour market and the wider economy remain highly contested. Jonathan Wadsworth presents a detailed analysis of the current immigration picture in the UK and the policy challenges the issue might pose for the next British government.

Polling data suggests that Brexit is viewed as the most important issue for voters ahead of the UK’s general election on 12 December. Immigration, which has previously been viewed as one of the most important issues, has experienced a relative decline in salience since the last general election in 2017, but its purported effects on the labour market and the wider economy remain highly contested. Jonathan Wadsworth presents a detailed analysis of the current immigration picture in the UK and the policy challenges the issue might pose for the next British government.

Most people have a sense that immigration has risen a lot in the UK recently. And indeed it has. About 9.5 million UK residents are immigrants, some one in seven (14.3%) of people now in the UK are immigrants, up from 3.8 million (7% of the UK population in the mid 1990s). This average rise disguises much more varied changes over time across and within regions, across occupations and industries.

Economists have long understood that these events reflect immigration decisions about where to go and what to do which are influenced by assessments of the costs and benefits of a move to another country. Individuals can decide to move and indeed leave or migrate elsewhere if economic and/or political conditions shift in favour of migration to other countries. Firms can decide to utilise migrant labour, train more, pay more, mechanise or move location according to their own assessments of the relative costs and benefits of each option.

Government policy and the performance of the economy also influence these costs and befits. The number of immigrants in the UK is also therefore a reflection of a series of economic and political events that have made the UK relatively more or less attractive to migrants over time. Equally, the attractiveness of the UK to migrants from outside the UK is influenced by relative economic circumstances but also by the relative costs of entry embodied in the visa and entry system.

Measure for measure

Knowing the number of immigrants living in the UK is something of an inexact science. There is no official count of resident immigrants, nor of inflows and outflows, despite, until recently, net inflows being a longstanding government target. Instead, there are different household surveys that are used to estimate these various stocks and flows. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) has a preferred measure of counting immigration flows (the numbers arriving and the numbers leaving), based on analysing the International Passenger Survey (IPS). This method has recently been downgraded to ‘experimental’ status because of concerns with coverage and weighting.

The only official data set that can provide a regular, timely estimate of the total number of immigrants living in the UK (not just the yearly flows in and out) is the Labour Force Survey/Annual Population Survey (LFS). This is the same survey that is used to measure the unemployment rate in the UK. The LFS also has detailed information on the characteristics of immigrants and those born in the UK. So if we want to compare, say, the educational attainment of immigrants and those born in the UK, or where immigrants live, or whether immigrants are more or less likely to be unemployed, or the effect of immigration on the wages of those born in the UK, the LFS is practically the only UK data set that can be used to investigate these and other related issues.

Currently, the two survey sources are sending conflicting signals. The LFS-based count says that the immigrant population has been static, and may have even fallen a little since 2017. In contrast, the IPS says that net inflows (inflows minus outflows) to the UK by immigrants have been resiliently positive, in the order of 250,000 a year even using the intermediate revisions made by the ONS to the IPS data. If more immigrants are coming to the UK than leaving, immigration must be rising. The two surveys are saying different things.

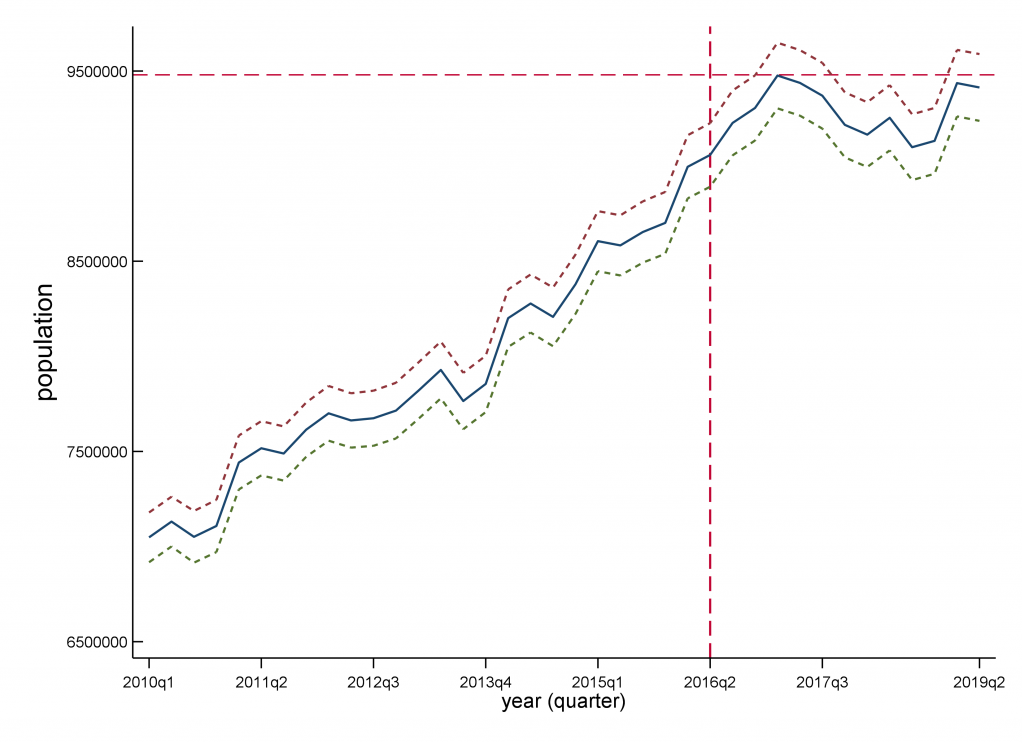

Admittedly, both data sources use different definitions of immigrants. The LFS defines immigrants based on country of birth and usual residence. The IPS uses nationality, as shown on respondents’ passports, to define immigrant status with an additional qualification that the survey respondent intends to stay for 12 months or more. So part of the difference is likely to be due to this. So both may be right. Equally, both may be wrong for different reasons. But the central point is that policy formulation and informed debate about immigration are currently compromised by the ambiguity in the data: the IPS says it’s going up, the LFS data suggests otherwise (figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1: IPS estimates of changes in the immigrant population in the UK

Note: Compiled using data from the International Passenger Survey (IPS).

Figure 2: LFS estimates of immigration population in the UK

Note: Compiled using data from Labour Force Survey/Annual Population Survey (LFS).

Immigration’s effects

Immigration still seems to matter much more politically than it does economically. Immigration’s effects on most areas of the economy appear to be small. There are neither large negative effects, nor large positive effects.

It is sometimes suggested that immigration could compromise public services by increasing demand and competition for publicly provided resources. Unlike the UK-born population, a majority of immigrants are in employment and so are over-represented among the total number in work. Immigrants are, however, a little over-represented in the unemployed and economically inactive populations, but under-represented among children and pensionable age populations – because they tend to arrive as adults and not all migrants stay in the UK until a pensionable age (or the current cohort of migrants have not been in the UK long enough to reach a pensionable age).

Immigrants are younger and therefore more likely to be healthier. They are also more highly qualified on average than the UK population, and more likely to be in (higher paid) work than the average UK-born individual. Together all this underlies the reason why several studies, summarised by the Migration Advisory Committee find that immigrants are net fiscal contributors, paying more in taxes than they receive in benefits and, as such, are less likely to put pressure on public services like the NHS or schools.

Immigration policy options

The policy options offered by the different political parties in this election vary from retaining the existing system to a points-based system that shows no favour for EU migrants over non-EU migrants.

Immigration to the UK contains three distinct groups: workers and their families; students; and refugees. All three groups are covered by different rules and visa schemes. Future policy has to balance the costs and benefits of changing the rules for each area. A new government has to decide essentially who gets in, for how long and at what cost among the many disparate groups of potential immigrants. This is not an easy task. The immediate consequences of Brexit, if it happens, may be very different from what governments may want from a long-term immigration strategy. Policy may have to be designed flexibly to address the resulting short-term versus long-term issues.

With regard to the labour market, firms with labour shortages can train more, automate more, change work practices (such as pay or working conditions) or move instead of using labour from abroad. Indeed, it may well be that the change in direction of EU immigration flows following Brexit has already forced some adjustment by firms, so the immediate migration response of increased outflows and a fall in inflows after the vote has forced firms to address the new reality without there being any change in policy. If not, sector-specific and time-limited or seasonal migration schemes (from the EU or elsewhere) could allow workers into the less skilled sectors until businesses had adapted to the new policy environment. The downside of such a policy is that sectors may postpone any changes to their business model.

Any quotas or work visas for EU nationals after Brexit are also likely to favour graduate sector jobs. This is partly because the existing immigration policy for non-EU citizens is almost exclusively restricted to graduate-level jobs and partly because the net fiscal contribution from graduates is likely to be higher than from non-graduate jobs. Whether there are more shortages in this area or in the vocational sector due to the UK’s relatively poor training record is open to discussion. It may be that a revised shortage list could be broadened, again, to include the type of shortage vocational jobs that were originally on the list.

Immigration could also be targeted at individuals rather than jobs, effectively reverting to a points-based system, a form of which was in place in the UK in the late 2000s but subsequently dropped by the coalition government of 2010-2015. Coming up with a coherent points system is not an easy thing to do, (the MAC are currently tasked with looking in to it). Targeting individual graduates may not help graduate sectors if the graduates migrate to less skilled occupations.

Occupation-based entry shortage schemes rather than individual points-based entry have the advantage that labour market signals can better determine which sectors are in shortage. Letting firms and workers interact within informed general government imposed guidelines (such as restricting entry to graduate or higher paying jobs) is probably a better way to get good job matches. Restricting by occupation rather than people will probably reduce migration flows more, since the set of eligible occupations is easier to restrict than a set of eligible individuals.

Limiting immigration to those with job offers in certain occupations does not, however, automatically restrict migration to these sectors. Students can work in the UK before and after graduation. Non-EEA family migrants can work in any sector in the UK. Firms can bring in employees from international subsidiaries in occupations not on a shortage list (inter-company transfers). Workers can leave jobs for other sectors.

There are also issues of regional or, more likely, country-specific immigration schemes to consider. Scotland has some additional leeway over its work route since it has its own shortage occupation list. Country/regional-based schemes are easier to operate with temporary visas. With permanent residence, individuals can move away from the area that sought to attract migrants, which can then negate the effect of the policy to attract migrants. But temporary visas bring other problems. If individuals are tied to a particular employer, this gives the employer more power over a worker than if the worker were free to choose where to work. Temporary visas increase the likelihood that some individuals may overstay the length of their visa.

The Immigration Skills Charge on any firm hiring labour from outside the EU has been in place since 2017. It is too early to tell whether this has deterred some firms from hiring, but knowledge of this policy and its effects would be welcome in helping decide whether and how to extend to hiring workers from the EU.

Conclusions

The options for future immigration policy are many and varied and there are no easy answers as to what to do or what to prioritise. Whichever party is in power after the election may well have an immigration policy that , like so many policies in the UK, evolves and reacts to events and the unforeseen consequences of previous actions.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article first appeared on our sister site, LSE Brexit. It gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. The report on which this blog is based is available here: CEP Election Analysis: Immigration.

_________________________________

Jonathan Wadsworth – Royal Holloway, University of London / CEP

Jonathan Wadsworth is a Professor of Economics at Royal Holloway, University of London and a Senior Research Fellow at the Centre for Economic Performance.

Just a detail, but I think an important one. The article is about immigrants and immiugration, but nowhere defines what these terms are used mean in this particular context. Is an immigrant anyone not born in the UK, or anyone holding only a non-UK passport?.(My wife was born abroad, because her father was in the Foreign and Colonial service, and the family went with him, but she is as British as me, and has a UK pasport.) Or is the discussion about recent immigrants in, say, the past decade, as opposed to Windrush immigrants and their descendants, some but not all of whom will have been born abroad? What about UK citizens who have made their homes abroad and taken the local nationality (such as my daughter, now French, and my wife’s nephew, now Portugese, who may perhaps return to the UK in their old age?

Clarification is needed.