A number of governments across the world have sought to regulate the pay of company executives to help reduce inequality. However, as Renira C. Angeles and Achim Kemmerling explain, efforts to control average levels of executive pay often overlook the inequality that exists between managers, firms and sectors.

A number of governments across the world have sought to regulate the pay of company executives to help reduce inequality. However, as Renira C. Angeles and Achim Kemmerling explain, efforts to control average levels of executive pay often overlook the inequality that exists between managers, firms and sectors.

Since the 1980s, there have been numerous scandals about the excessive growth of pay for company executives. Enron is just a very prominent example in recent years. As a reaction, governments have experimented with regulating top executive compensation (TEC) in several ways: the Clinton administration in the United States put a cap on TEC tax deductibility; while both the Obama administration and the EU imposed a pay cap for firms in need of a bailout after the global financial crisis. Some countries have even tried to go further. For instance, there was a referendum in Switzerland to limit CEO pay to workers by a ratio of 12:1 (in most countries the actual ratio is much higher). The referendum failed.

These initiatives have become salient at a time of general increases in top income shares and growing overall inequality. Prominent economists have argued that TEC inflation significantly contributes to growing income inequality by driving up the income at the top. This can ultimately damage the legitimacy of democracies.

However, governments’ attempts to regulate or even control executive pay lead to very different outcomes across countries. While in some countries (e.g. the Nordics) the rise of TEC has been relatively moderate, in others (e.g. the United States or the UK) it has escalated. The academic literature has targeted these cross-country differences and has given reasons why some governments are more successful in halting excessive wage growth for top managers. These include cooperation with strong trade unions, high tax rates on corporate and personal income, and shareholder protection laws among others.

The importance of redistributive institutions

We argue, however, that one important aspect of such attempts is often overlooked: how do such attempts deal with the heterogeneity among managers and the income inequality among CEOs? We do know that there are huge differences between managers belonging, say, to the top 10, 1 and 0.1 percent respectively. However, the literature disagrees over the extent to which this inequality is due to inequalities between managers, between firms, or entire sectors. For example, finance and real estate are often mentioned as sectors which have seen the highest growth in TEC. Therefore, there is a clear case of heterogeneity and inequality among managers, but not all government initiatives reflect this.

Consider the four main institutions mentioned (unions, corporate income tax, personal income tax and shareholder protection). Only two of these are robust to the problem of heterogeneity arising at different levels (individual, firm or sector). These institutions are the only ones that tackle inequality directly on the basis that they are (potentially) redistributive. The first institution is cooperation with unions, given, on average, (centralised) unions tend to care about wage inequality within firms and among individuals. The second is personal income taxation, which occurs at the individual level (regardless of which firm or sector a manager belongs) and managers face a progressive tax rate. Neither corporate taxation (at least most forms of it) nor shareholder protection exhibit these features. They target the average manager, no matter who this is and in what type of firm or sector he or she works.

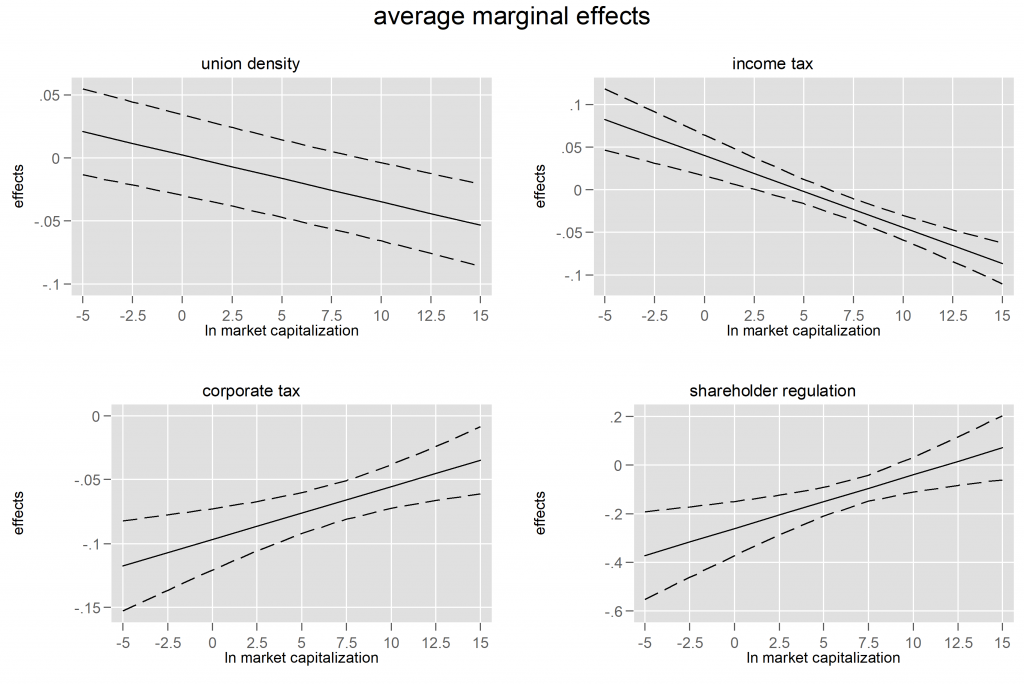

This leads to a simple prediction. While all four types of interventions might dampen the average TEC, only personal income taxation and the role of unions matter for inequality among managers. To show this, we look at the effect of all four types for firms of different sizes in terms of market valuation. This follows a large literature on the growing disparities between small and large cap firms. If our argument about the power of redistributive institutions is correct, we should not only look at the direct (aggregate) impact of institutions on TEC, but also at the gap between very large firms (in market value) and the rest.

We test this idea with a new dataset on TEC for 17 countries over a period of 10 years. The figure demonstrates our main findings. All four interventions affect the average level of TEC, but corporate income taxation and shareholder protection have a stronger (more visible) effect on the average level of TEC (as seen by the range on the y axis). However, only personal income taxation and the strength of unions affect small and large cap firms differently. In both cases, the redistributive effect sets in, i.e. very big firms see more of a depression in TEC. In other words, only these two types of intervention target the relative differences among managers.

Figure 1: Effect of union density, income tax, corporate tax and shareholder regulation on changes in top executive compensation

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in Socio-Economic Review.

Inequality is back on the political agenda, and top executive compensation is an important driving force of overall inequality. Governments differ very much in their capacity (and political will) to address the issue. We argue that redistributive institutions still play a significant, but somewhat underappreciated role in moderating TEC in 21st century capitalism. The strength of trade unions and personal income tax rates, notably, matter precisely because they address the individual pay heterogeneity among managers (as well as firms and sectors) directly. They are particularly relevant for “large-cap” firms. Other means, such as corporate income taxation and or regulation, do this much less. If inequality among managers is a key driving force for a general rise in top executive compensation as previous studies have argued, initiatives that strengthen such redistributive institutions are an important and robust strategy for governments to respond to rising inequality.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in Socio-Economic Review.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Kiefer (CC BY-SA 2.0)

_________________________________

Renira C. Angeles – NORCE

Renira C. Angeles – NORCE

Renira Angeles is a Postdoc Fellow at NORCE Norwegian Research Centre in Bergen (Social Science) and conducts research within the fields of income inequality, health economics, social/health inequalities and the welfare state in Norway. She graduated from Central European University in 2018.

Achim Kemmerling – University of Erfurt

Achim Kemmerling – University of Erfurt

Achim Kemmerling is Gerhard Haniel Professor of Public Policy and International Development in the Willy Brandt School of Public Policy at the University of Erfurt, Erfurt, Germany. He has published on issues of tax policy, social and labour market policies, and fiscal federalism and worked as a consultant to the German Federal Parliament (Deutscher Bundestag), the German Society for Technical Cooperation (former GTZ, now GIZ) and the European Investment Bank (EIB).