Faced with ageing populations and strains on their public finances, many countries across Europe have endeavoured to reform their pension systems, yet these reforms have varied substantially in their content and aims. Leandro N. Carrera and Marina Angelaki present findings from a novel study of eight European countries to highlight the key factors that lead countries to undergo significant pension reforms.

Faced with ageing populations and strains on their public finances, many countries across Europe have endeavoured to reform their pension systems, yet these reforms have varied substantially in their content and aims. Leandro N. Carrera and Marina Angelaki present findings from a novel study of eight European countries to highlight the key factors that lead countries to undergo significant pension reforms.

Governments in Europe and around the world must increasingly focus on pension policy, given population ageing and the impact of public pensions on government finances. Since the late 1980s, European countries have engaged in a variety of pension reforms, yet these have been far from uniform in terms of their content and direction. Broadly, they have ranged from changes to eligibility criteria, to introducing a mandatory pillar of private pensions.

The theoretical approaches used to analyse pension reforms have highlighted different factors such as socio-economic and institutional features, political mobilisation and their interactions. Nonetheless, while comparative studies have been good at describing how different conditions may combine, these analyses have been highly descriptive and focused on a few cases.

In a recent study, we provide stronger comparative evidence on the specific combination of causes that lead to significant pension reform. Specifically, we show that significant pension reform (i.e. a reform entailing the introduction or elimination of a mandatory second pillar of private pension accounts) is best understood as a result of different pathways combining multiple causes in different ways.

Methodologically, we use Fuzzy Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) to find out the conditions, or combinations of them, that must be present for significant pension reform to occur. The analysis is based on 48 cases of pension reform in eight European countries (Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom) between 1986 and 2014.

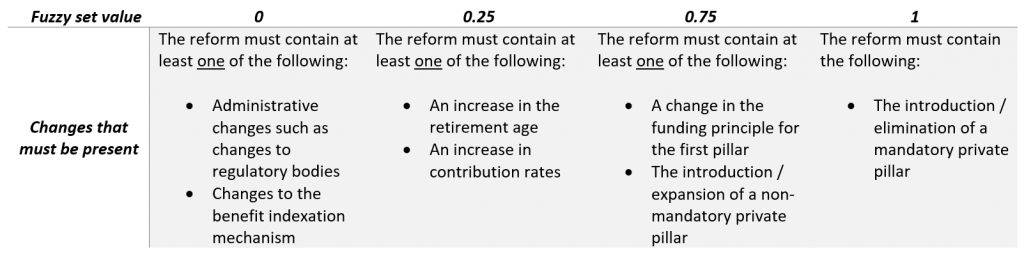

The cases analysed comprise reforms ranging from parametric ones, where a parameter of the system is changed such as the retirement age or the benefit indexation formula, to paradigmatic ones leading to the introduction or elimination of a mandatory second pillar of private accounts and thus a significant change in the design of the pension system. The cases were calibrated into four-point fuzzy sets according to their key features as shown in the table below.

Table 1: Key features of pension reforms

Note: In Qualitative Comparative Analysis, a number is assigned to indicate whether a particular element is present in a case. For instance, if we wanted to examine how EU membership affects a country, we might look at a group of countries and assign them a value of 1 if they are EU member states and a value of 0 if they are not in the EU. Fuzzy Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis is similar, but instead of simply assigning a 1 and a 0, different ‘sets’ are identified corresponding to the degree to which a particular element is present. For instance, we might assign a state that is in the EU a value of 1 and a state that has no relationship with the EU a value of 0, while non-EU states that participate in the EU’s single market (e.g. Norway) are given a value between 0 and 1 to reflect the fact they have a closer relationship. In this table, four ‘sets’ of pension reforms are shown, indicating the degree to which the reform altered the previous system. A value of 0 indicates a reform that is not significant, while a value of 0.25 indicates a more significant reform, and so on up until a value of 1, representing a significant reform of the system. For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in the Journal of Social Policy.

The causal conditions examined based on the institutional and structural socio-economic factors highlighted by the literature are the following: a strong labour movement (SL), significant legislative fragmentation (LF), significant unemployment (UN) and a significant government deficit (GD). These were calibrated into five-point fuzzy sets: 1; 0.75; 0.5; 0.25; 0.

The results indicated that significant unemployment is a necessary condition for significant pension reform to take place, meaning that it must be present in all instances of the outcome. While this finding lends some support to the literature focusing on the role of socio-economic conditions, our results also show that unemployment needs to be combined with other factors to be sufficient for leading to significant pension reform.

The first pathway indicates that unemployment must be combined with the absence of legislative fragmentation, thus lending some support to the institutional “veto player” approach to pension reform, which states that a less fragmented political system may be more conducive to reform. As an illustration, the Hungarian 1997 reform that introduced a new mandatory private pillar is covered by this pathway. The reform took place in the context of high unemployment during the 1990s due to the transition from state socialism to capitalism and was facilitated by the government’s near majority in Hungary’s parliament, led by the centre-right Fidesz party and its allies. This was key to pushing through pension reforms as part of a package of market-oriented reforms.

The second pathway combines significant unemployment with high government deficit levels, thus highlighting the “structural economic” route to reform. Using some case substantive knowledge, we argue that this illustrates the case of the Hungarian reform of 2011. While the large majority of the Fidesz led government cannot be disregarded, in this case the large government deficit in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis played a key role, as the government decided to eliminate the private pension pillar as a “quick fix” to improve its financial position by switching those funds to the Treasury.

The third pathway shows that unemployment must be combined with a strong labour movement. This combination seems to contradict the assumptions of the power resource theory, which had argued that a strong labour movement would typically oppose significant reforms. We contend that the 1995 Italian reform is covered by this pathway. The reform led to a change in the funding principle of the first pillar from defined benefit to notional defined contribution. This change was made possible through a trade-off strategy between the government and a strong labour movement, where labour accepted the changes to put the system on a sustainable path in exchange for concessions for the protection of older workers.

The results provide information about how many of the cases each solution covers (coverage). As such, the coverage coefficient bears some resemblance to the R2 (coefficient of determination) in regression analysis. The overall coverage of our model is over 0.65, which indicates that more than 65 percent of instances of the outcome are explained by the four combinations identified in the solution. The results also provide a consistency value, which measures the degree to which a causal combination, or the solution as a whole, is a subset of the outcome (sufficient). Consistency values are around 0.8, indicating highly consistent results.

Fuzzy set Qualitative Comparative Analysis is a powerful tool for illustrating in a systematic way how conditions can be combined to lead to an outcome and should be increasingly used in other social and public policy research designs. Yet, this method is not without its limitations. One of the most significant challenges is to consistently calibrate a complex outcome and a set of causal conditions into fuzzy set values.

But such limitations can be addressed, namely by resorting to both quantitative and qualitative assessments grounded in theoretical and substantive knowledge of the cases. As such, future social policy and public policy research could gain from the insights of our analysis, while bearing in mind the limitations of fsQCA and the ways in which these can be addressed.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in the Journal of Social Policy

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image: Demonstration in Madrid against reforms of the Spanish public pension system, Credit: Adolfo Lujan (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

_________________________________

Leandro N. Carrera – LSE

Leandro N. Carrera – LSE

Leandro N. Carrera is a research associate at the London School of Economics’ Public Policy Group and works at the UK Pensions Regulator.

–

Marina Angelaki – Panteion University

Marina Angelaki – Panteion University

Marina Angelaki teaches European and global social policy at Panteion University, Athens.