Slovakia held parliamentary elections on 29 February. The election saw Smer-SD, which has been in power since 2012, suffer a significant drop in support, slipping to second place behind the opposition Ordinary People party. Michael Rossi presents five key takeaways from the results.

Slovakia held parliamentary elections on 29 February. The election saw Smer-SD, which has been in power since 2012, suffer a significant drop in support, slipping to second place behind the opposition Ordinary People party. Michael Rossi presents five key takeaways from the results.

Two years after the murder of Slovak investigative journalist Ján Kuciak and his fiancée Martina Kusnirova that shocked the country and served as a catalyst for a disillusioned but otherwise passive population to take action, voters participated in parliamentary elections that may alter the country’s image and political trajectory.

The murders underscored the widely held belief that Slovakia is run by a triangulated cadre of powerful oligarchs, political bosses, and organised criminal syndicates. Marián Kočner, the Slovak businessman accused of ordering the hit on Kuciak, has a number of ties with both the criminal underworld and Slovakia’s political elite, including the country’s most prominent political power broker Robert Fico, leader of the ruling Smer-SD (Direction-Social Democracy) that has governed the state for the last eight years.

Though corruption and illiberal democratic government are no strangers to either Slovakia or any other Central (or Eastern) European state for that matter, the public outcry over Kuciak’s murder has translated into voter anger at Smer-SD in particular and the poor state of affairs of Slovakian politics in general. Shortly after the murder, Fico was forced to resign as Slovakia’s prime minister. One year later in a much publicised presidential election, the lawyer and environmental activist Zuzana Čaputová, a political novice who entered the race on an anti-corruption platform, bested the Fico-endorsed Maroš Šefčovič in a race lauded in western media circles as a defeat of populism and nationalism.

The 29 February parliamentary elections were projected to be a continuation of public anger at the status quo and an opportunity to elect political alternatives. But given the nature of the number of parties competing along with a majority of them espousing some form of national populism, the outcome offers little optimism for anyone hopeful Slovakia is turning towards liberal democracy. At present, there are five clear takeaways from the electoral results.

- The election was a referendum on Smer-SD

No political party in Slovakia is currently perceived by its citizens to be more synonymous with corruption, clientelism, nepotism, and patronage than Smer-SD. For nearly fifteen years (including four in opposition), Smer-SD has dominated all forms of Slovakia’s political life and has, in many ways, inherited the mantle of illiberal government and political oligarchism from the Vladimír Mečiar era of the 1990s.

While it is not unexpected that a society disillusioned with current political, economic, and social conditions lays blame with the incumbent government, public anger at Smer-SD is particularly acute in the wake of Kuciak’s murder. Its leaders openly engage in graft and flaunt their wealth, privilege, and political immunity to citizens increasingly beset by economic woes, limited job opportunities, crumbling state services, and the brain drain abroad.

At the top of this pyramid sits Robert Fico who, like a party boss of the 1990s, dispenses favours and offers legal protection to allies. Those like Kočner whom he can’t defend are simply disavowed out of political self-preservation. The hubristic confidence he exudes reminds one of Donald Trump, who along with other political strongmen like Viktor Orbán and Vladimir Putin, are seen as role models. Like Trump, Fico is prone to turn any national event or tragedy into a personal issue, such as when he recently spoke at one of the commemorations of Kuciak’s murder and opined that “if it wasn’t for the murder, I’d be standing here in front of you today as Prime Minister with 30% support.”

Given the public anger reflected in last year’s presidential election, it is no surprise this sentiment carried into this year’s parliamentary contest, as all analyses leading up to the February elections predicted not just a loss for Smer, but a loss depriving them of the ability to form a governing coalition. All political opponents from centre-left to far-right were united in one common goal: to unseat Smer as the ruling party and dismantle its Tammany-like political machine. The predictions were correct. Smer-SD lost nearly half its seats, and while it still placed second, it stands little chance of being in a governing coalition.

Figure 1: Preliminary results of the 2020 Slovakian parliamentary election

Note: Referenced from the Slovak Spectator

- But it also should have been an endorsement of PS/Spolu

Less clear than Smer’s loss was what would become of the Progressive Slovakia/Together (PS/Spolu) coalition after its victory in both Slovakia’s presidential and European Parliamentary elections last year.

At the time, Zuzana Čaputová’s victory was hailed as a major milestone for Slovakia’s beleaguered liberal democratic movement, and a blow to the perception that Central Europe is awash in national populism. So important was her candidacy that a country usually ignored outside the region suddenly made headlines across American, British, and European newspapers. Since becoming president, Čaputová is Slovakia’s most trusted politician, the only politician whom people trust more than they distrust, and according to The New Yorker, is “a lone political voice in a sea of demagoguery”. Given the conditions of Slovakia’s political culture of disappointment, this is a rare honour to hold.

However, that trust has not translated into votes for her party coalition, as PS/Spolu failed to cross the electoral threshold necessary to seat members. Like most parliamentary democracies, Slovakia operates along a “5% rule” that requires parties needing at least 5% of the popular vote in order to qualify for seats in parliament. But because PS is working in a pre-arranged coalition with Spolu, the threshold is raised to 7%.

At last count, PS/Spolu finished with 6.96% of the vote, a hair’s length away from entry. Some may discuss the lost opportunity of offering Za L’udí, a small conservative-progressive party that just passed the threshold at 5.77%, a third spot in its coalition. Either way, the low votes are a massive disappointment for a party and a movement seen as a champion of liberal democracy, feminism, LGBTQ rights, secularism, and cosmopolitanism. Additionally, it is a confirmation that Čaputova’s victory last year was less a stand against populism and conservatism, and more a rejection of corruption.

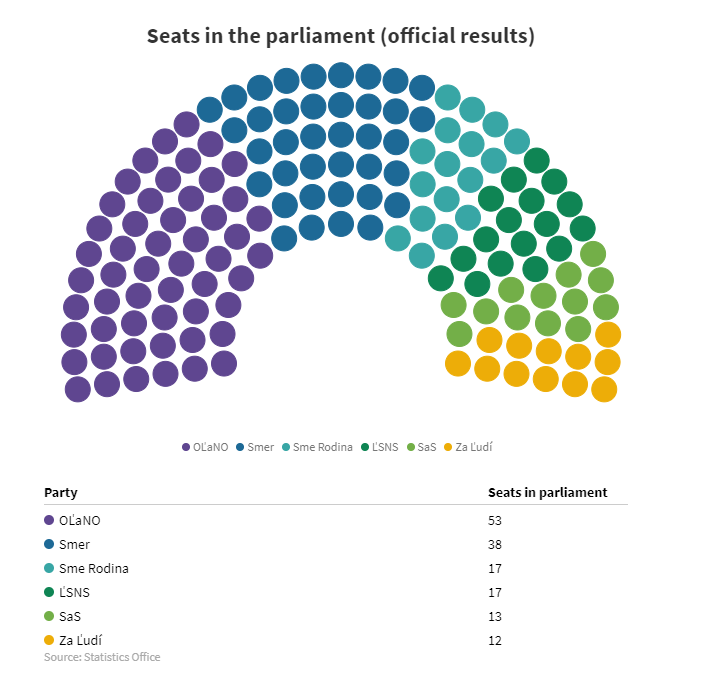

Figure 2: Seats in parliament following the 2020 Slovakian parliamentary elections

Note: Referenced from the Slovak Spectator

- The four largest parties embrace some form of populism; three of which are conservative and parochial

The big winner in Slovakia’s parliamentary election is the Ordinary People and Independent Personalities (Obyčajní Ľudia a nezávislé osobnosti, OĽaNO) Party, which earned a massive 25% of the votes and a mandate to form a new government with 53 seats in a 150 seat legislature. An even bigger winner is its party head Igor Matovič, whose political charisma and acumen elevated the party’s popular standing within the last month and a half.

Though Matovič can certainly be credited for his ability to mobilise voters and identify socio-economic problems, his party being centre-right and operating on philosophies of Christian-democracy certainly helped in a country where the electorate is largely conservative, Catholic, and parochial. This also helps explain the electoral success of two other parties: the Eurosceptic We Are Family (SME Rodina) Party, and the far-right People’s Party – Our Slovakia (Ľudová strana – Naše Slovensko, ĽSNS), which came in third and fourth respectively. What this means is that Slovakia’s parliament will be dominated by conservatives, populists, parochialists, and remnants of Smer-SD’s entrenched elite, leaving little room for liberal democratic progressivism and almost no left-wing policies.

The largest threat to Slovakia’s political scene is the evolution of ĽSNS from a peripheral neo-fascist movement to a mainstream party. Its long-time leader Marian Kotleba fashions himself as the heir to the Slovak Republic, a wartime Nazi collaborationist state, and has openly promoted anti-Roma policies similar to far-right movements in Hungary. Kotleba has recently attempted to have his party become more socially accepted. That means abandoning both the black uniforms of the Nazi-era Hlinka Guard and the night-time torchlight marches through cities and towns.

But along with this modernisation comes a type of political savviness indicative of right-wing populist groups eager to connect with “ordinary” citizens and present themselves as the only socio-political alternative to a series of parties tainted with links to oligarchs and scandals. Additionally, the ĽSNS has been successful via social media reaching out to younger Slovaks disillusioned with the system and eager to support quick-fix solutions to seemingly insurmountable problems.

The problem with ĽSNS isn’t that it stands a chance of entering government, but rather that in an attempt at distancing themselves from the radioactivity of ĽSNS, other right-wing conservative parties have begun mimicking their rhetoric and advocating several of their policies that they know resonate with Slovaks. For older Slovaks, this means steadfast adherence to faith, family, and fatherland. For the disaffected youth, this means anti-elitism, anti-globalism, and anti-capitalism. Whatever the reason, Kotleba’s policies are becoming normalised in Slovak political discourse.

- Coalition forming seems uncertain

The present arrangement of parties that qualified for seats in parliament presents another conundrum. Both Smer-SD, which came in second with 18.2% of the vote (38 seats), and ĽSNS, which came in fourth at 7.9% (17 seats) are both seen as radioactive by other groups but possess large enough percentages to make coalition forming around them cumbersome, unruly, and altogether unstable.

As the party with the plurality of votes, OĽaNO is given a mandate to begin talks with other parties for coalition forming. Barring the obvious cordon-sanitaire placed on Smer and ĽSNS, Matovič is left with a handful of small parochially conservative parties that if cobbled together could form a governing majority: SME Rodina, a right-wing populist and anti-immigration party that borrows much of its positions from ĽSNS (17 seats); Freedom and Solidarity (Sloboda a Solidarita, SaS), a libertarian and Eurosceptic party (13 seats); and For the People (Za L’udí, ZL’), a newly formed conservative albeit pro-European political party formed around former Slovak president Andrej Kiska (12 seats).

But in an election that was largely, if not entirely, a referendum on the incumbent regime, the disparate opinions, goals, and aspirations of each party will now become apparent as the common thread of unseating Smer was met and second-tier goals become deal makers or breakers. OĽaNO is conservative, but perhaps not conservative enough to accept a partnership with SME Rodina. Yet given the dearth of options, the post Smer government may resemble a rag-tag group of parties and movements that are stitched together simply to deny the second-place incumbent the ability to govern; an arrangement that has happened elsewhere in Eastern and Central Europe over the past twenty years, and one that usually ends in political breakdown.

- There is no progressive left-wing movement in Slovakia

Beyond the collapse of Smer’s political authority and legitimacy, the most glaring issue in Slovakian politics today, like most states of Central and Eastern Europe, is the near absence of any true left-wing political party. While often derided as populist and nationalist, Smer is, at least officially, a left-of-centre party. Its loss of legitimacy, coupled with PS/Spolu’s disastrous performance at the polls, means Slovakia is dominated by right-wing conservative groups.

The plight of the political Left in Eastern Europe stems from enduring stigmas of socialism and anything remotely “Marxist” as emblematic of the Communist authoritarian period. Added to this was an international push throughout the globalising 1990s advocating unfettered free-market capitalism as the sinecure for all political, economic, and social woes, which made an environment for social democratic parties extremely difficult to grow. What left-wing parties that did exist followed models of Third Way neoliberalism that looked to international trade and eventual EU-membership as substitutes for state-sponsored social welfare.

But in the ensuing decades that saw a widening economic gap between rich and poor that was often associated with the politically connected versus the disenfranchised, growing public dissatisfaction was exploited by a new collection of national populist parties like ĽSNS, Fidesz in Hungary, and the Law and Justice Party in Poland. Despite all of them being right-wing, xenophobic, and anti-global, they successfully tapped into public grievances against rising costs of living versus stagnant wages, limited social services that had been cut to make the state more attractive to foreign investment, and a concentration of wealth and affluence in a handful of urban centres at the negligence of smaller towns and the countryside.

Much of the successes of right-wing national populist parties like ĽSNS and similar movements throughout the region stems from the Right’s ability to tap into legitimate grievances that would otherwise be defended by left-wing socialist groups, and channel that anger into protest votes at the neoliberal status quo.

The popularity of populist parties isn’t that they are reactionary, but that they speak to issues more mainstream parties lauded by international observers as standard-bearers of democracy either ignore, are unable, or uninterested in addressing. The majority of Slovaks agree their country is systemically plagued by corruption, oligarchism, and clientelism. Historically, these problems were targeted by left-wing groups advocating social democracy, equality, and accountability. Today, these causes are taken up by national populist groups that frame accountable government within an ethnocentric model of national defence.

In so many words, the populist Right wins where the progressive Left is non-existent. The establishment of genuine social democratic parties that represent the working class could go a long way in returning these right-wing extremist parties both to the political periphery and below the parliamentary electoral threshold.

Following last year’s presidential election, Slovaks demanded change, and in so doing voted the incumbent parties out of power in parliament. But in the process, they also placed the country’s government squarely in the hands of anti-system parties. While initial signs indicating a movement towards a neoliberal pro-EU Centre was premature, it is unclear how and where a new governing coalition will direct the country. What is clear is that the public remains mobilised and empowered following Kuciak’s murder and Matovič’s new government will be held to the same scrutiny and accountability as Fico’s. It also implies that if Smer-SD is ever to recover, they will have to rebuild themselves after getting rid of Fico.

Stay tuned.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: alpe89 (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

_________________________________

Michael Rossi – Long Island University – Brooklyn

Michael Rossi – Long Island University – Brooklyn

Michael Rossi is Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science and Director of the International Relations Program at Long Island University – Brooklyn.

Could you re-evaluate your thoughts in the article considering current situation – I would be very interested in your opionion, you seemed to have been more sceptic than most people in my country, Slovakia – including me – do you any other predictions where we go from here?