The principle of differentiated integration, under which states participate in EU policies selectively, has become a core feature of the European Union. But little is known about the attitudes of citizens toward this form of integration. Drawing on a new study of Denmark’s 2015 referendum on the country’s opt-out from EU Justice and Home Affairs cooperation, Frank Schimmelfennig and Dominik Schraff highlight that differentiated integration has the potential to improve citizens’ assessments of the EU’s democratic legitimacy.

The principle of differentiated integration, under which states participate in EU policies selectively, has become a core feature of the European Union. But little is known about the attitudes of citizens toward this form of integration. Drawing on a new study of Denmark’s 2015 referendum on the country’s opt-out from EU Justice and Home Affairs cooperation, Frank Schimmelfennig and Dominik Schraff highlight that differentiated integration has the potential to improve citizens’ assessments of the EU’s democratic legitimacy.

Differentiated integration starts from the assumption that it helps the European Union to adjust to the growing heterogeneity of its member states and to the increasing contestation of its policies. By allowing some states to move ahead with integration while others stay behind, differentiated integration takes into account diverse national integration preferences and capacities. It facilitates intergovernmental agreement and enables states to integrate at the level they need, prefer and are able to handle. It thus increases not only the problem-solving and decision-making efficiency of the EU, but also its ‘demoi-cratic’ legitimacy as a voluntary community of states and peoples.

Yet we know very little about what citizens actually think of differentiated integration. Specifically, does differentiation improve citizens’ assessment of democracy in the EU and thereby strengthen the EU’s legitimacy as a political system? We cannot simply infer from intergovernmental agreement on differentiated integration that citizens approve, too. Citizens have conflicting integration preferences. For instance, if their state opts out of deeper integration, Eurosceptics are content, whereas Europhiles are displeased. If differentiated integration was just a zero-sum game between winners and losers, it would fail to enhance the legitimacy of the EU overall.

We argue that differentiated integration has the potential to overcome this zero-sum game. For one, we assume that the institution of differentiated integration as such – the right and opportunity to choose between different levels of European integration – improves the democratic legitimacy of the EU for both winners and losers. Having a national choice from the menu of European integration rather than being confronted with a take-it-or-leave-it proposition, and being able to make this choice through democratic procedures of parliamentary or direct-democratic ratification, offsets the losers’ displeasure with the outcome at least partially.

Moreover, the gains that Eurosceptics experience from obtaining opt-outs for their country are likely to be larger than the perceived losses of the Europhiles. Typically, Europhiles are supporters of mainstream parties. The parties they vote for not only regularly win elections, form governments and shape policy-making, but have also supported the incremental deepening and widening of European integration. For these reasons, Europhile mainstream party supporters tend to have a high level of satisfaction with democracy and political efficacy. Against this background, losing an opt-out vote now and then is unlikely to affect their perceptions of political legitimacy strongly.

By contrast, Eurosceptics are typically supporters of fringe or challenger parties that are unlikely to win elections and form governments, and they have seen the EU deepen and widen against their preferences for a long time. For both reasons, they have a personal history of losing, leading to comparatively low levels of satisfaction and efficacy. Against this experience of long-term losing, winning opt-outs from integration may boost their perception of the EU’s democratic legitimacy.

We test this argument in an analysis of Danish perceptions of political efficacy around the 2015 referendum, in which Danish voters were asked to give up Denmark’s opt-out from integration in Justice and Home Affairs. Our analysis benefits from the lucky circumstance that the referendum took place during a Eurobarometer survey (EB 84.4) asking respondents, among other things, whether their voice counts in the EU. This question taps the perceived political efficacy of citizens, an important condition of political participation but also a widely used measure of diffuse support for the political system. We are therefore able to test (in a quasi-experimental regression discontinuity analysis) the effect that the confirmation of the Danish opt-out in the referendum has had on the perceived legitimacy of the EU among Danish citizens.

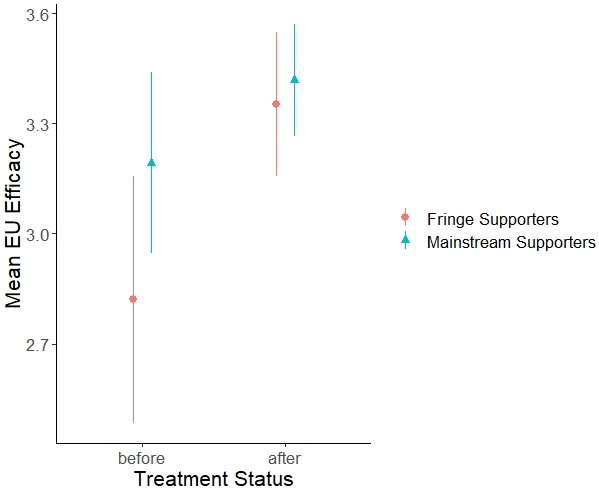

The analysis shows that the opt-out referendum boosted people’s perceptions of their ability to affect EU politics. On a four-point scale, the differentiation vote increased EU efficacy by .35 points (or 8.75 percentage points). We also find that, while Europhile mainstream party supporters did not change their attitudes significantly, Eurosceptic fringe party supporters improved their perceptions of political efficacy in the EU substantively by 12.5 percentage points (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Local average treatment effect across mainstream and fringe supporters

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper.

While our analysis does not provide direct evidence on the relative importance of the procedural and the outcome effects of the opt-out vote, it seems plausible that the result was mainly responsible for the Eurosceptics’ increase in perceived EU efficacy. After all, they had known for many months that they would have the opportunity to cast their vote. For this reason, it is implausible to attribute the rise in Eurosceptics’ EU efficacy to the referendum experience as such rather than to the experience of being able to effectively shape the European integration of their country.

By contrast, the procedural legitimacy of the democratic referendum may have contributed to the Europhile losers’ consistently high perceptions of efficacy. In addition, we find that the opt-out vote did not affect Danes’ assessment of national political efficacy or the perceived EU efficacy of non-Danish respondents. We thus conclude that the effective opportunity to choose differentiated integration benefited the legitimacy of the EU specifically.

Naturally, findings from a single case need to be treated with caution and call for more studies on citizens’ evaluation of differentiated integration. But Denmark can be considered a hard case for finding differentiation effects because Danish citizens enjoy a high level of efficacy in general and have obtained opt-outs for a long time. Our results therefore suggest that differentiated integration can improve citizens’ assessments of the EU’s democratic legitimacy, indeed.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying EUI Working Paper RSCAS 2020/11. The paper is based on work conducted as part of the collaborative project “Integrating Diversity in the European Union” (InDivEU). The authors gratefully acknowledge support through the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement No 822304.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: News Øresund (CC BY 3.0)

_________________________________

Frank Schimmelfennig – ETH Zürich

Frank Schimmelfennig – ETH Zürich

Frank Schimmelfennig is a Professor of European Politics and member of the Center for Comparative and International Studies at ETH Zürich. He is also a Schuman Fellow at the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies of the European University Institute in Florence and chairs the Scientific Board of the Institut für Europäische Politik, Berlin.

Dominik Schraff – ETH Zürich

Dominik Schraff – ETH Zürich

Dominik Schraff is a Senior Scientist and SNSF Ambizione Fellow in the European Politics Group in the Center for Comparative and International Studies at ETH Zürich. He obtained his doctorate in 2017 from the University of St. Gallen, having previously studied at University College London and the University of Mannheim.