What do financial markets make of the economic impact from the Covid-19 pandemic? Iain McMenamin, Michael Breen and Juan Muñoz-Portillo track how the markets have judged the risk of an Italian default since the start of the crisis. They write the market response appears to have been driven in part by the level of solidarity shown from other EU states.

What do financial markets make of the economic impact from the Covid-19 pandemic? Iain McMenamin, Michael Breen and Juan Muñoz-Portillo track how the markets have judged the risk of an Italian default since the start of the crisis. They write the market response appears to have been driven in part by the level of solidarity shown from other EU states.

One of Europe’s sickest political economies is sadly also one of the countries that is suffering most from the pandemic. Italy has a debt that is one-third larger than its economy; its economy has hardly grown in the era of Europe’s single currency; and its political elites have not come up with a credible plan to improve the country’s prospects. As the virus ripped through northern Italy and deaths escalated, investors quickly became more sceptical about Italy’s ability and willingness to pay its debts.

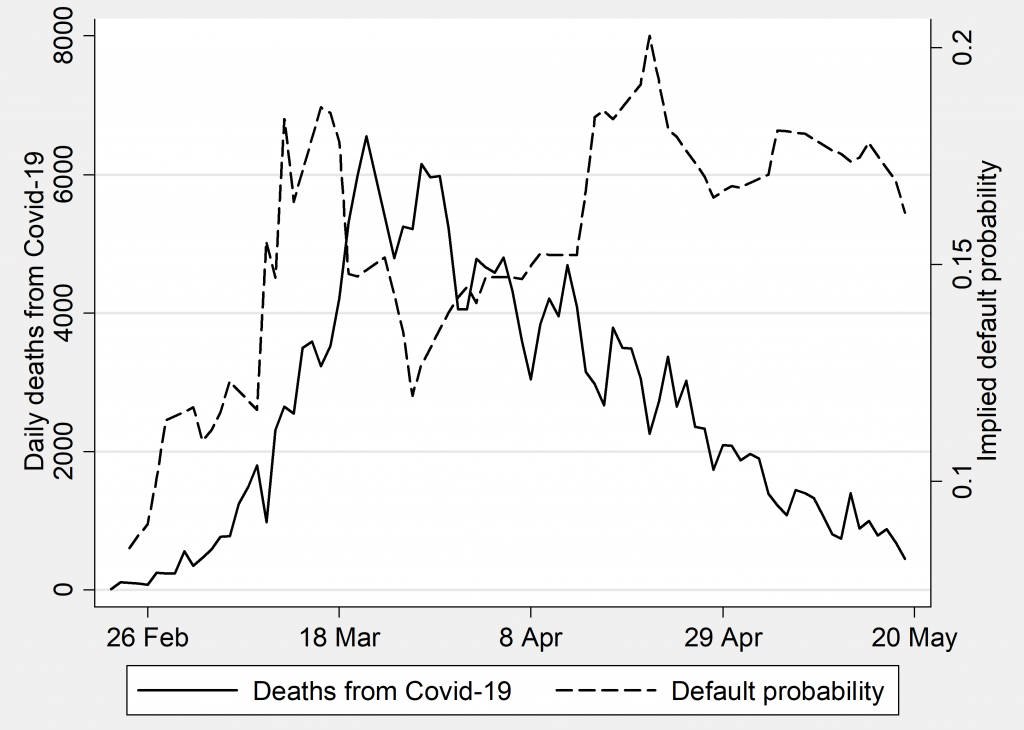

A credit default swap is an insurance policy against a default on a debt contract. The graph below plots the probability of Italian sovereign default, implied by credit default swap (CDS) trading, against the number of deaths attributed to Covid-19 each day. We can see the two climbing alarmingly quickly together in the first half of March. When the pandemic plateaued, markets appear to have been somewhat reassured about Italian debt.

In April, remarkably, the relationship disappeared. If anything, it seems to suggest that the fewer Italians that die, the more likely Italy is to renege on its debts! Of course, it wouldn’t have made sense for the markets to head back to normality as the pandemic receded because the damage to the Italian economy, government finances, and the risk of political radicalisation all remained. Nevertheless, there was no drastically new information in relation to any of these three interlinked factors that would have explained why markets should have perceived a further jump in the probability of default.

Figure: Italy, the virus, and the markets

Note: The data source is Eikon. The implied default probability is derived from trading of five-year Italian credit default swaps.

Instead, the climb in the Italian CDS price in April most likely reflects European international political economy, rather than the domestic political economy of the health crisis in Italy. April began with the Dutch blocking various proposals to help countries with debt burdens exacerbated by the virus. It ended with a judgment from the German Constitutional Court that appeared to limit the European Central Bank’s autonomy to stabilise markets and even to challenge the supremacy of European law over national law. In April, markets re-evaluated the chances of an Italian default because northern European levels of solidarity with Italy were turning out to be lower than they had expected. In May, more positive signals from Brussels, Paris, and Berlin, and some signs of compromise in Amsterdam seem to have been greeted positively by markets.

At least that’s a reasonable reading of the graph. It’s hard to attribute financial market movements to specific events, because traders try to anticipate events in making decisions on what and when to buy and sell. This is known as “pricing in”. In a recently published paper, we construct an innovative measure of whether markets received surprising information about the political economy of debt during fifteen elections in eleven Eurozone countries. We show that the more stable a country’s debt position, the more its elections disrupted financial markets. Each stable country is one of several contributing to European solidarity. Northern countries can take turns at playing to their national constituencies – whether voters, party members, or constitutional lawyers!

This logic is again revealing itself in the Covid crisis. Italy’s underlying condition is a high level of debt with little prospect of a reduction. Europe’s underlying condition is not so much having Italy as a member. Rather, it is that no single member state is responsible for the stability of its partners. Stable countries can free-ride on each other’s solidarity. When they do so, markets withdraw money from places like Italy. This appears of be the diagnosis of financial markets. We can expect further spikes in pressure on Italy, as other European countries wobble on support for their fellow member state.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in the International Political Science Review

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Iain McMenamin – Dublin City University

Iain McMenamin – Dublin City University

Iain McMenamin is a Professor of Comparative Politics and Head of the School of Law and Government at Dublin City University.

–

Michael Breen – Dublin City University

Michael Breen – Dublin City University

Michael Breen is an Associate Professor in the School of Law and Government at Dublin City University.

–

Juan Muñoz-Portillo – University of Costa Rica

Juan Muñoz-Portillo – University of Costa Rica

Juan Muñoz-Portillo is a Professor in the School of Political Sciences at the University of Costa Rica.