A new round of data from the Chapel Hill Expert Survey, covering 2019, is due to be released. The survey, which estimates the positions of political parties on a variety of ideological and policy issues, offers an invaluable tool for assessing political competition in Europe. Ryan Bakker, Liesbet Hooghe, Seth Jolly, Gary Marks, Jonathan Polk, Jan Rovny, Marco Steenbergen, and Milada Anna Vachudova draw on the latest data to examine where European political parties now stand on European integration, and how their positions have changed since the last full survey was conducted in 2014.

Support for populist parties that claim to defend ‘the people’ against the establishment has risen across Europe – and this sentiment appears to extend to the European Union (EU). From the Northern League in Italy and the Forum for Democracy in the Netherlands to the AfD in Germany, many populist parties denounce European integration as an elitist project that undermines the interests of ordinary people and the nation.

Yet in the streets and at the ballot box, parties and movements that support European integration have also strengthened. During his successful campaign, French President Emmanuel Macron waved the European flag – and so have many pro-democracy demonstrators on the streets of Prague and Warsaw. Using new expert survey data on party positions, we ask: Where do European political parties stand on European integration, and how have their positions changed over the last five years?

Since 1999, the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES) has been estimating the positions of political parties in the member states of the European Union on a variety of ideological and policy issues. With the newly released 2019 data, we can compare how parties have changed their positions over time. What we find is that parties generally show limited programmatic flexibility. This is even the case for European integration during these last five eventful years: Across all member states there has been, overall, very little change between 2014 (the date of our last full survey) and 2019, as shown in Figure 1. In 2014, the average party position was 4.93 on a 1-7 scale, with higher values meaning more support for the EU. In 2019, the average party position on European integration was substantively indistinguishable at 5.05.

Figure 1: Support for European integration in 2014 and 2019

Note: The boxplot shows the median, 25th and 75th percentile of support for European integration. Source: chesdata.eu

This overall continuity in party positions on the EU is remarkable given the dynamic nature of European politics over this 5-year period that included both the refugee crisis in 2015 and the referendum on Britain leaving the EU in 2016. Our data reveal that political parties maintained steady support for the EU from 2014 and 2019. But this does not tell the whole story.

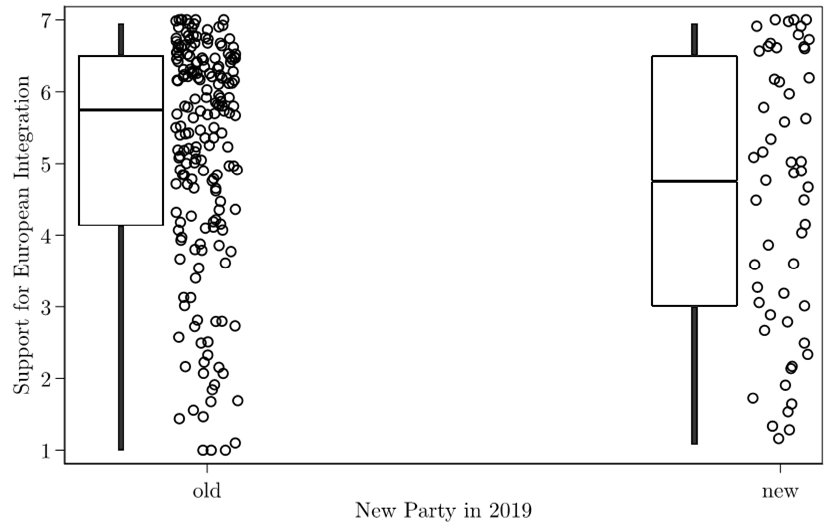

‘New’ parties are substantially more Eurosceptic than ‘old’ parties

When we compare the EU positions of parties that are new to the 2019 data with the EU positions of parties that were also included in our 2014 survey, we see a meaningful divergence. The ‘new’ parties in the 2019 data have a mean EU position of 4.5 while the ‘old’ parties have a mean EU position of 5.2, nearly a full point more supportive of the EU on the 1-7 scale. Established parties thus stand in stark contrast to new parties that challenge the status quo and that are considerably more Eurosceptic.

Figure 2: Old vs. new party support for European integration in 2019

Note: The boxplot shows the median, 25th and 75th percentile of support for European integration. The dots represent political parties. Source: chesdata.eu

The finding that new parties are, on average, more anti-EU than older parties is consistent with the expectation that party system change comes from rising parties rather than from established parties changing their positions. Although a small number of new parties are ardent proponents of the EU, most are Eurosceptic challenger parties, such as the Brexit Party in the UK and Vox in Spain. These challenger parties mobilise support by criticising the political establishment – and that usually includes the EU.

New parties emphasise anti-establishment rhetoric

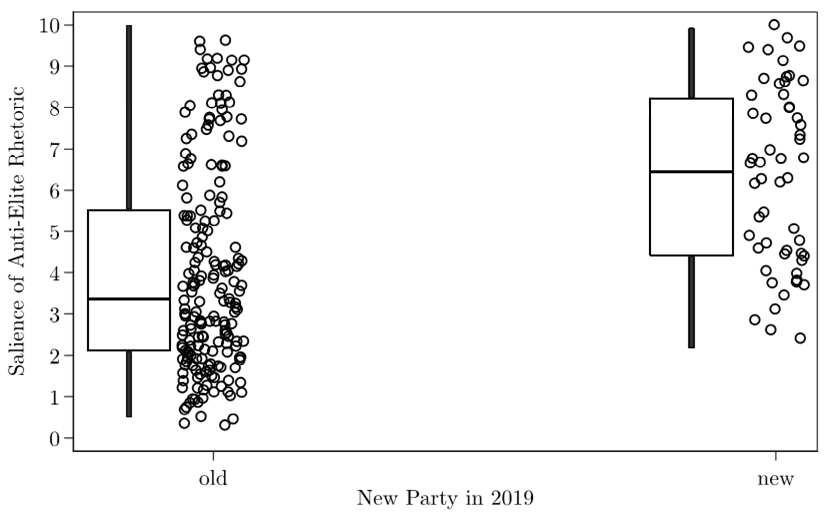

We can identify the challenger parties in our data clearly by looking at the salience of anti-establishment rhetoric in the positions of all parties.

Figure 3: Old vs. new party salience of anti-elite rhetoric in 2019

Note: 0 = Not important; 10 = Important. The boxplot shows the median, 25th and 75th percentile of support for European integration. The dots represent political parties. Source: chesdata.eu

New parties have an average anti-elite salience score of 6.3, on a 0-10 scale, with 10 representing the highest levels of anti-elite salience. This is considerably (and statistically significantly) higher than 4.0, the mean for the older parties. Criticising the political establishment thus animates the campaigns of new parties more than old parties.

However, as Figure 3 shows clearly, there is plenty of anti-elite sentiment among parties that were already in existence in 2014. Indeed, it is anti-elitism – not whether a party is new or old – that reveals whether a party supports or opposes European integration. Anti-elitism fits Euroscepticism like a glove: the statistical association between the two is a strong 0.76. One is hard pressed to find a new pro-European party that is also anti-establishment. Of the 17 new parties in our dataset that support European integration (6 or more on our 7-point scale) just one is anti-elite/establishment (6 or more on the 0-10 scale). Conversely, of the eight new parties that are strongly Eurosceptic, every party is strongly anti-establishment.

The eastern distinction

The post-communist states that have joined the EU (‘the East’ for short) are distinct but comparable to the West. They are distinct in that European integration has provided an important anchoring reference for democratic politics in opposition to the bloc’s communist authoritarian past. They are comparable to the West in that contemporary politics is increasingly defined by competition between anti-European nationalism and pro-European transnationalism.

In the East, the dynamics of opposition to European integration and the rise of new parties stand out in three ways. First, party systems in the East are more organisationally fluid and institutionally weaker than their western counterparts, which leads to more party deaths and births across the ideological spectrum. Second, even some radical nationalists – who would be expected strongly to oppose European integration in the West – moderate their anti-EU political appeals in the east because of EU financial transfers and other visible benefits of membership.

Third, populist parties that define ‘the people’ in ethnic and religious terms have won power in some states and engineered significant backsliding to illiberal democracy or (in Hungary) authoritarian rule. In response, a number of democratic – and also decisively pro-European – political forces have risen up to oppose them. While fragmented and often eclipsed by populist and nationalist incumbents, these new parties and movements use European integration as a symbol of democracy. This has been reflected in the growing polarisation of political competition as parties oppose one another across the nationalist-transnationalist divide.

This brings us to a fundamental difference between the East and the West, as Figure 4 makes clear. In the West, established ‘old’ parties are far more supportive of European integration than ‘new’ parties that tend to take anti-establishment stands. In the East, old and new parties are nearly indistinguishable in their EU positions, with new challenger parties as pro-European as the established parties. In the East, therefore, anti-establishment and pro EU positions can go hand in hand.

Figure 4: EU position between old and new parties in eastern Europe

Note: The boxplot shows the median, 25th and 75th percentile of support for European integration. The dots represent political parties. Source: chesdata.eu

As we write, Covid-19 has shaken European societies and their health systems to the core, brought economic destruction, and exposed Europe’s fragile solidarity. But Covid-19 presents an opportunity as well as a challenge. An effective EU response built on solidarity may fortify pro-EU opposition forces in the East and strengthen established parties in the West against their populist opposition.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Contando Estrelas (CC BY-SA 2.0)

_________________________________

Ryan Bakker – University of Essex

Ryan Bakker – University of Essex

Ryan Bakker is Reader in Comparative Politics at the University of Essex. He is on Twitter @with2Ks

–

Liesbet Hooghe – UNC Chapel Hill / EUI

Liesbet Hooghe – UNC Chapel Hill / EUI

Liesbet Hooghe is W.R. Kenan Professor at UNC Chapel Hill and Robert Schuman Fellow at the EUI Florence. She is on Twitter @HoogheLiesbet

–

Seth Jolly – Syracuse University

Seth Jolly – Syracuse University

Seth Jolly is Associate Professor of Political Science at Syracuse University. He is on Twitter @sethkjolly

–

Gary Marks – UNC Chapel Hill / EUI

Gary Marks – UNC Chapel Hill / EUI

Gary Marks is Burton Craige Professor at UNC Chapel Hill and Robert Schuman Fellow at the EUI Florence.

–

Jonathan Polk – University of Copenhagen / University of Gothenburg

Jonathan Polk – University of Copenhagen / University of Gothenburg

Jonathan Polk is Associate Professor at the University of Copenhagen and the University of Gothenburg. He is on Twitter @jon_polk

–

Jan Rovny – Sciences Po

Jan Rovny – Sciences Po

Jan Rovny is Associate Professor at Sciences Po in Paris. He is on Twitter @JanRovny

–

–

Marco Steenbergen – University of Zurich

Marco Steenbergen – University of Zurich

Marco Steenbergen is Chair for Political Methodology at the University of Zurich.

–

–

Milada Anna Vachudova – UNC Chapel Hill

Milada Anna Vachudova – UNC Chapel Hill

Milada Anna Vachudova is Associate Professor of Political Science at UNC Chapel Hill.