The so called ‘revolving door’ problem refers to the apparent tendency of politicians to pursue lucrative career opportunities after they leave politics. But to what extent does this image of politicians as opportunists seeking to benefit from their time in office match reality? Drawing on a new study covering Germany and the Netherlands, Clint Claessen, Stefanie Bailer and Tomas Turner-Zwinkels explain that while some politicians do use their political roles as a stepping-stone in their career, this is perhaps less common than we imagine.

The so called ‘revolving door’ problem refers to the apparent tendency of politicians to pursue lucrative career opportunities after they leave politics. But to what extent does this image of politicians as opportunists seeking to benefit from their time in office match reality? Drawing on a new study covering Germany and the Netherlands, Clint Claessen, Stefanie Bailer and Tomas Turner-Zwinkels explain that while some politicians do use their political roles as a stepping-stone in their career, this is perhaps less common than we imagine.

In Germany and the Netherlands, famous cases of politicians who benefit from their time in office are numerous. Think about former German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder, who became CEO of the company Nord Stream 2. Or former Dutch Minister of Transport, Camiel Eurlings, who became the CEO of KLM. And what about Ronald Pofalla, who heavily criticised Schröder for going to Nord Stream but ended up making the switch to a lucrative lobbying position at Deutsche Bahn after his own time in office.

The result of these prominent transitions is that an image of opportunistic politicians who obtain huge benefits from their time in office is created among the public and the media. Moreover, many politicians do not even try to hide their ambitions; Gerhard Schröder, for example, has the following quote on his website: “No question about it. Personal advancement – the desire to advance myself, to advance my social standing – has played a crucial role in my life.” The question is, however, to what extent this image holds true for other politicians in parliament and whether they succeed in this regard.

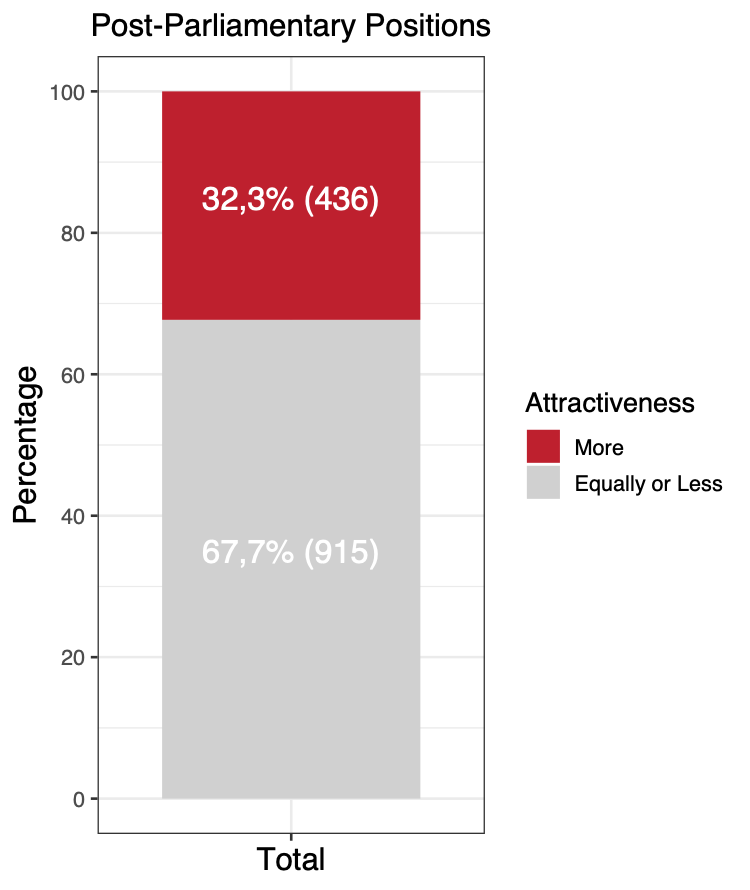

To examine this issue, we looked at all parliamentarians who left office after 1986 in the Netherlands and 1998 in Germany (n = 1,351). We found that only 32% obtained more attractive positions during their post-parliamentary careers (see figure 1). In other words, the vast majority of our national politicians in the Netherlands and Germany have not used public office as a stepping-stone for their career.

Figure 1: Post-parliamentary career success

Note: Absolute numbers in brackets. For more information, see the authors’ accompanying study.

In our study, we looked at the most attractive positions a politician obtained in the five years after he/she left office and hand coded positions as more attractive when they entailed a higher salary and/or higher status. This coding was then checked for reliability with six other coders in the Netherlands and Germany.

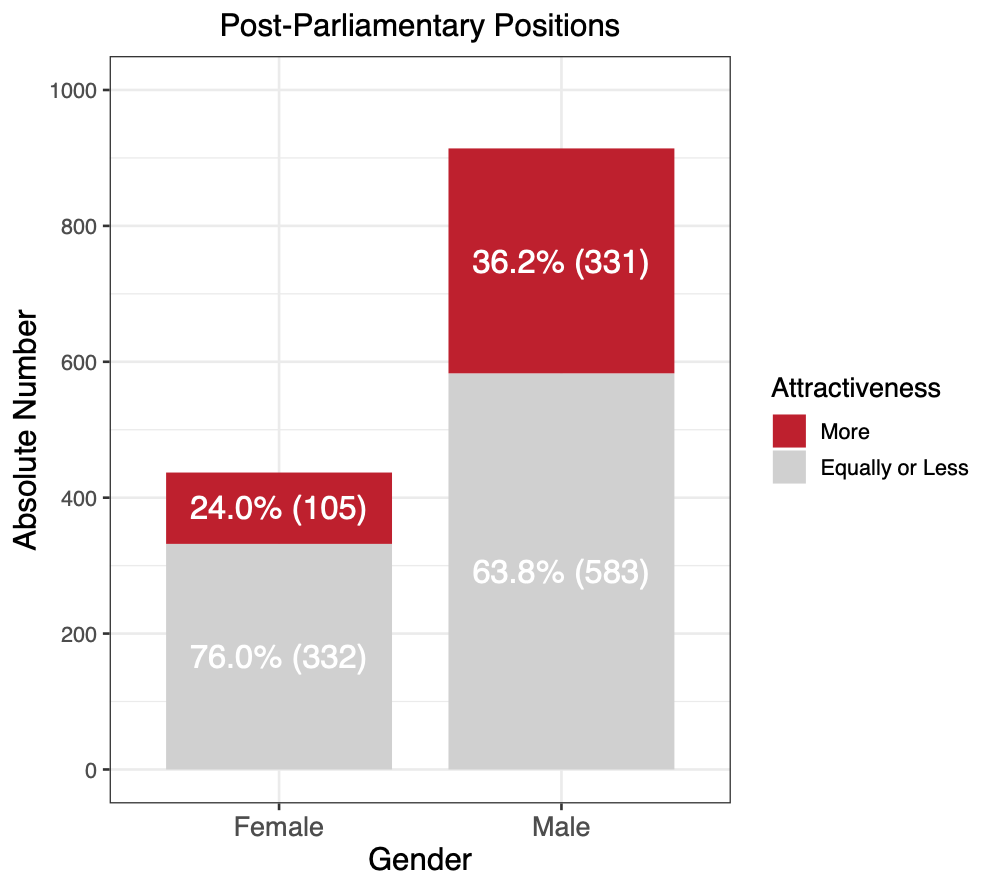

In addition to uncovering descriptive post-parliamentary career patterns, a few other interesting findings were obtained. Firstly, we found a substantial gender gap; female parliamentarians do significantly worse than male parliamentarians when they leave office. For example, while 36% of male parliamentarians obtained a more attractive position after leaving office, only 24% of female parliamentarians did so (see figure 2). Even when we control for various potential confounders, this gap is still significant and substantial. Independent of education level, the socioeconomic status of pre-parliamentary careers, higher positions in parliament or in the cabinet, the economic outlook of the party and years in office amongst other factors, this effect still holds.

Figure 2: Post-parliamentary career success by gender

Note: Absolute numbers in brackets. For more information, see the authors’ accompanying study.

While the literature talks about tendencies for women to be more risk and competition averse, it is safe to assume that most MPs already had to overcome major competitive hurdles and that this select group of people is not particularly shy of competition or political risk, regardless of gender. What could make a difference for female parliamentarians, however, is that many important selection committees in both the private and public sphere are still male dominated and could have an in-group bias. Another similar factor at play is related to party politics. This is the relative closeness of party patronage. In other words, female parliamentarians are offered significantly less attractive portfolios and less powerful roles in government.

Although the literature does not conclusively indicate why female parliamentarians fare less well than male parliamentarians, some other findings are more straightforward. What we define as legislative achievement, that is, the attainment of important parliamentary positions, has significant implications for career success. For example, cabinet members do better in both the public and the private sector and members of the party executive and members of business committees do better in the private sector. On the other hand, negative achievement also has significant implications in the other direction. That is, MPs who fail to be re-elected or re-nominated or MPs who are of retirement age are much less likely to obtain attractive positions. Overall, it is therefore fair to say that only a select minority of parliamentarians in Germany and the Netherlands is really able to use their time in office as a stepping-stone for their careers.

The revolving door

The fact that only a minority benefits from office in their later career is even more true when looking at the revolving door. When viewing post-parliamentary careers in terms of subsets, that is, the public and the private sectors, we see a large drop in the number of politicians that obtain more attractive positions. For the public sector, 45% of politicians achieve their progressive ambitions, while in the private sector only 23% do so. For female parliamentarians, the latter percentage is even smaller, namely 16%. Put differently, the vast majority of parliamentarians in Germany and the Netherlands do not make use of the revolving door to the private sector.

We like to tell stories about our MPs and define politicians’ group characteristics, portraying them as opportunistic, ambitious and ideological. The empirical reality, however, is messier. The party matters, education matters, gender matters, and higher parliamentary positions matter, but they matter slightly differently in the public and in the private sectors, and overall they do not take away the fact that for the majority of MPs, parliament itself is really what matters most in their careers. Perhaps that last fact is a more comforting thought than the image of the power-hungry career politician that is often portrayed in the popular news media.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying article in the European Journal of Political Research

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Greg Wass (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

_________________________________

Clint Claessen – University of Basel

Clint Claessen – University of Basel

Clint Claessen is a Doctoral Researcher at the University of Basel. His interests include political careers and intra-party dynamics. He is currently investigating the relationship between ideological party leader shifts, electoral success and political promotion.

Stefanie Bailer – University of Basel

Stefanie Bailer – University of Basel

Stefanie Bailer is a Professor of Political Science at the University of Basel. She previously worked as an Assistant Professor for Global Governance at ETH Zurich and as a Senior Assistant at the University of Zurich.

Tomas Turner-Zwinkels – University of Basel

Tomas Turner-Zwinkels – University of Basel

Tomas Turner-Zwinkels is a Post-doctoral Researcher at the University of Basel. His key research interest is the study of political careers and digital democracy. He completed his PhD at the University of Groningen.