In July, EU heads of state and government finally reached agreement on a recovery package to tackle the socio-economic fallout from Covid-19. Daniel F. Schulz writes that although the agreement was unprecedented in its scope, Europe’s recovery strategy will draw heavily on the existing analyses and institutional structures of the European Semester. Ultimately, Europe’s leaders will be betting on the potential of renewable energy and digital services to create millions of jobs across the EU, suggesting that large-scale upskilling programmes may become a prominent feature of member states’ labour market policies.

In July, EU heads of state and government finally reached agreement on a recovery package to tackle the socio-economic fallout from Covid-19. Daniel F. Schulz writes that although the agreement was unprecedented in its scope, Europe’s recovery strategy will draw heavily on the existing analyses and institutional structures of the European Semester. Ultimately, Europe’s leaders will be betting on the potential of renewable energy and digital services to create millions of jobs across the EU, suggesting that large-scale upskilling programmes may become a prominent feature of member states’ labour market policies.

When July’s marathon European Council summit finally overcame the sharp divisions among European leaders, the prevailing mood among policymakers and commentators was euphoria. ‘Next Generation EU’ has been called a ‘real game-changer’, a ‘huge step forward’ for the EU, or even Europe’s ‘Hamilton moment’, and there can indeed be little doubt that the agreement sends a strong signal for strengthening the European project. Yet sceptics were also quick to point out that a large pot of money alone cannot make up for a lack of strategy, pointing to the critical issue of how the new recovery fund will be used. While issuing common debt implies a milestone for the EU, much depends on it being used for productive purposes so that it will also be seen as ‘good’ debt, as Mario Draghi recently pointed out.

So, what kind of investments and reforms can we expect to come out of the recovery plan? While the details of implementation are, of course, impossible to foresee, the institutional design of the fund contains hints about which priorities are likely to prevail. The new Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) will be ‘firmly embedded in the European Semester’ (originally established in 2010), showing how, in EU policymaking, past agreements often influence future solutions. By adding financial firepower, the RRF significantly upgrades this relatively mundane instrument of policy coordination, thereby strengthening the European Commission’s power to influence member state economies. Member states keen on getting their share of the funds have to submit so-called ‘recovery and resilience plans’ for Commission approval. Following Commissioner Paolo Gentiloni, the Commission’s assessment of the national plans will then depend on ‘whether they effectively address the relevant challenges identified in the European Semester’.

Hence, a look at the track-record of the European Semester throughout the past decade offers important clues on what types of reforms we are likely to see. In a recent study (co-authored with Jörg Haas, Valerie D’Erman, and Amy Verdun), we analysed more than 1,300 country-specific reform recommendations (CSRs) which the EU issued to euro area countries and found that many recommendations keep coming back consistently. This suggests that the Commission has a pretty clear idea about the reforms it wants member states to pursue – and that it will likely continue pushing these issues once the new recovery fund gives its demands more weight.

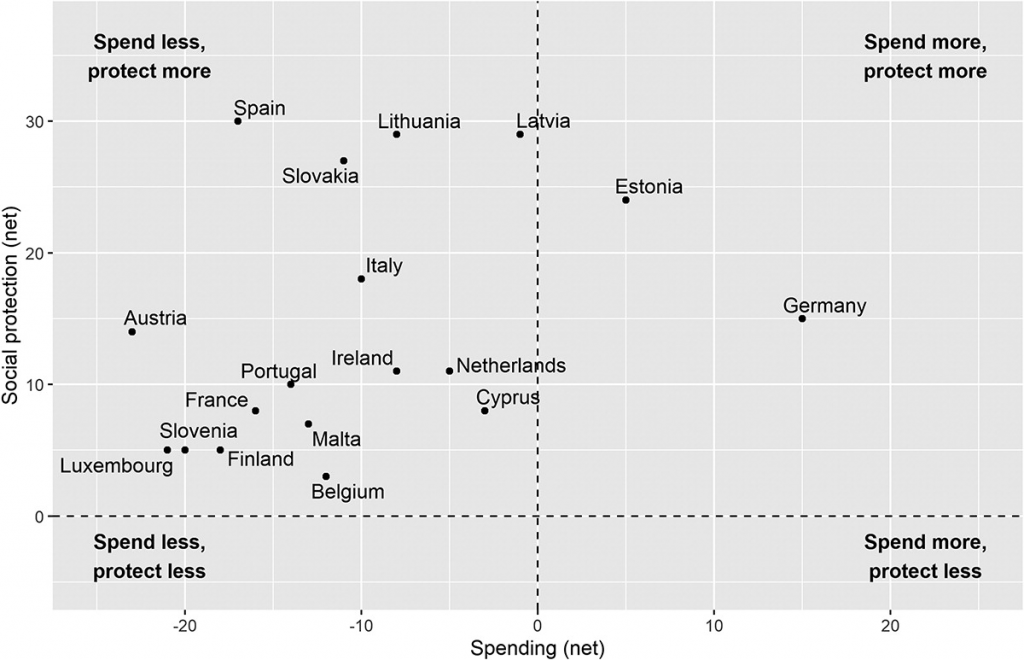

The good news first. By adding non-repayable grants as reform incentives, the RRF has the potential to overcome a key weakness of the European Semester: its unimpressive implementation record. In the past, the lack of effective carrots and sticks has meant that recommendations were often simply ignored. The lack of financial incentives has arguably been a prime obstacle which was only heightened by some inherent tensions between different recommendations: many countries were told to reduce public deficits while, at the same time, increasing social protections for vulnerable groups (see the top-left quadrant in Figure 1 below). Given that measures to improve education, family support, or training the unemployed tend to be costly, the Semester’s ineffectiveness in times of fiscal austerity should not come as a surprise. Thanks to the juicy carrots implied by the new RRF grants, however, the revamped Semester may finally overcome such apparent contradictions.

Figure 1: Reform recommendations concerning spending and social protection (2012-18)

Note: Net scores are calculated by deducting the number of CSRs that call for less social protection/spending from the number of CSRs calling for more. Source: Haas, D’Erman, Schulz & Verdun 2020

A closer look at those costly recommendations to improve social protection reveals the Commission’s overwhelming emphasis on active labour market policies (ALMPs). More than a third of all recommendations in this area involve activation and ALMPs, typically focused on training the low-skilled, the young, and the long-term unemployed. The second most prominent set of ‘social’ recommendations focuses on education, followed by measures to improve healthcare and childcare, and the adequacy of social assistance and services. In line with the flexicurity concept, the Semester thus carries strong elements of both security and flexibility, and is outsider-oriented in the sense that the bulk of measures target the low-skilled and unemployed. These measures typically do not focus on protecting workers from the market but, as Kathleen Thelen suggests, on actively adapting their skills to what the market demands.

This focus on training and education in the Semester sits well with the stated goal of using the recovery fund to invest in the ‘digital transition’. While upskilling for the digital age has arguably been an implicit goal for quite some time, it was not until 2018 that Ireland, Italy, and Portugal became the first to receive explicit calls for investing in digital skills as part of their CSRs. Going forward, this appears an obvious area where the past focus of the Semester and the Commission’s new strategies intersect. The hope is that widespread investment in digital skills will solve the EU’s perennial problems of high (youth) unemployment and dual labour markets – particularly in the South. Publicly funded training and education programmes to strengthen digital skills could thus become a prominent feature of the reforms the new recovery fund will support.

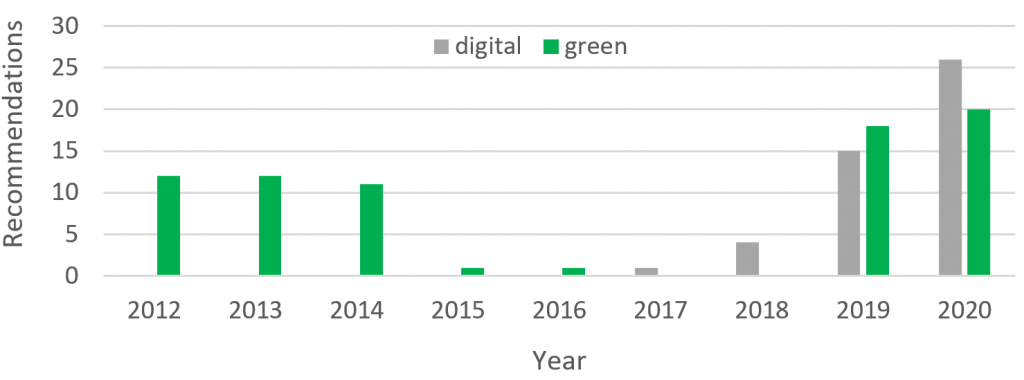

Figure 2: Recommendations mentioning ‘digital’ or ‘green’ reforms (2012-20)

Note: Compiled by the author

What about the recovery plan’s other main priority, the green transition? While Ursula von der Leyen put the ‘European Green Deal’ front and centre in her bid for the Commission presidency, the ‘old’ Semester CSRs tackled environmental issues only sparsely and partially. During the first few cycles (2012-14) the Commission focused primarily on shifting the tax burden from labour to environmental taxation, but environmental aspects faded from sight during the Juncker Commission (see Figure 2). Hence, the past track-record holds fewer lessons for how exactly an amended Semester process will support green policies in member states.

Experts nevertheless argue that the Semester holds the most promise as a steering instrument for the green transition, and there has been a clear revival of ‘green CSRs’ during the past two years (Figure 2). New sections on environmental sustainability and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in the annual Country Reports also suggest that the new Commission is getting serious about greening the European Semester. Beyond an apparent emphasis on clean energy in the 2020 CSRs, however, the reform priorities do not seem as clear as in the case of the digital transition.

In sum, the European recovery strategy places its bets on the potential of renewable energy and digital services to create millions of jobs across the Union. As the new RRF utilises the existing analyses and institutional structures of the European Semester, it could likely inherit its emphasis on large-scale education and training programmes to foster digital skills, especially among the young. This would be in line with the Semester’s long-standing initiatives to tackle labour market dualisation and youth unemployment, which previously lacked funding. Beyond the continuity this would imply, Mario Draghi recently spelled out a moral imperative for doing so: the unprecedented debt created by the pandemic ‘will have to be repaid mainly by those who are young today [and it] is therefore our duty to equip them with the means to service that debt.’

For more information, see the author’s recent study in the Journal of European Integration (co-authored with Jörg Haas, Valerie D’Erman, and Amy Verdun)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: European Council

_________________________________

Daniel F. Schulz – University of Agder

Daniel F. Schulz – University of Agder

Daniel F. Schulz is postdoctoral fellow at the University of Agder’s Jean Monnet Centre of Excellence ‘LabDiff’. He also collaborates in the context of a Jean Monnet Network ‘EUROSEM’ with Amy Verdun and Valerie D’Erman at the University of Victoria, where he previously worked as a postdoctoral fellow and lecturer. He holds a Ph.D. from the European University Institute and has published in outlets such as JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, Politics and Governance, and the Journal of European Integration.