A common response to the Covid-19 pandemic across Europe has been for states to promote social distancing. Yet the level of compliance from citizens has varied substantially between countries. Drawing on data from Switzerland, Neha Deopa and Piergiuseppe Fortunato provide an illustration of the impact cultural attitudes and behavioural norms can have on compliance with social distancing measures.

A common response to the Covid-19 pandemic across Europe has been for states to promote social distancing. Yet the level of compliance from citizens has varied substantially between countries. Drawing on data from Switzerland, Neha Deopa and Piergiuseppe Fortunato provide an illustration of the impact cultural attitudes and behavioural norms can have on compliance with social distancing measures.

Rarely in history have we witnessed such a homogeneous policy response to a shock as in the case of the Covid-19 pandemic. In an attempt to contain the spread of the virus and reduce the load on healthcare systems, virtually all European countries have adopted restrictive measures aimed at reducing individual mobility and inducing social distancing.

Interestingly, the rate of compliance with such measures has varied enormously. This raises the question of why similar policy measures have had such a different impact across European countries. Our hypothesis is that, in the absence of perfect enforcement capacity by states, cultural attitudes and behavioural norms, which typically vary from country to country, can make an important difference and explain deviations in voluntary compliance. This is all the more so when it comes to individual mobility decisions, which entail a delicate trade-off between the chance of contracting (or diffusing) a disease and the costs associated with significant alterations of daily activities.

Switzerland as a case study

In a recent paper, we have tested this hypothesis, assessing whether (and how) culture can mediate the social distancing process. We relied on phone location tracking records of 3,000 individuals, collected by Intervista on behalf of the Swiss Federal Statistical Office (FSO). We focused on Switzerland because it provides a unique case study; identical public health measures have been enacted in distinct linguistic geographical areas with deep cultural and historical roots.

Our analysis focuses on two important dates. The first is 25 February, when the first Covid-19 case was reported in Switzerland, marking the beginning of the outbreak in the country. The second is 16 March, when the Swiss government declared an “extraordinary situation” over the coronavirus, instituting a ban on all private and public events and closing places such as restaurants and bars.

Cultural identity and mobility

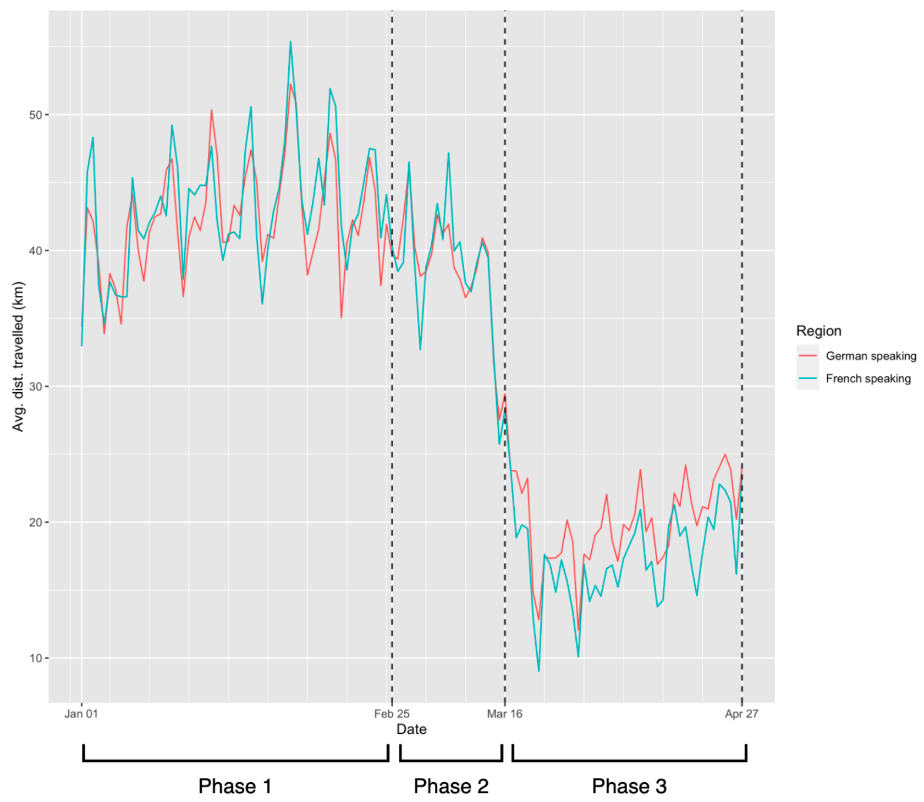

We found that German speaking cantons were much less responsive to the federal request to “stay at home” and in fact reduction in mobility during the emergency was significantly lower in this region. This is depicted in Figure 1 that shows the relationship between mobility and linguistic regions using the raw data and comparing the average distance travelled daily in German cantons (in red) with the rest of the country (in blue) between the beginning of January and the end of April. Although there is a marked drop in mobility for both areas, there is a clear difference between the two, a difference that becomes even more evident after the government declared the “extraordinary situation”.

The trend depicted in the figure, however, may depend on a series of variables associated with the linguistic-cultural identity, such as the different incidence of the pandemic or the quality of the healthcare system in place. To dispel these doubts, we estimated the differential evolution of mobility in areas with different linguistic-cultural roots over the different phases of the emergency, controlling for canton and daily fixed effects, number of Covid-19 cases reported and fatalities at the canton level, and for a rich set of geographic, demographic, and socio-economic indicators.

Figure 1: Daily mobility (average distance travelled in a day) across the linguistic regions of Switzerland

Note: Compiled by the authors.

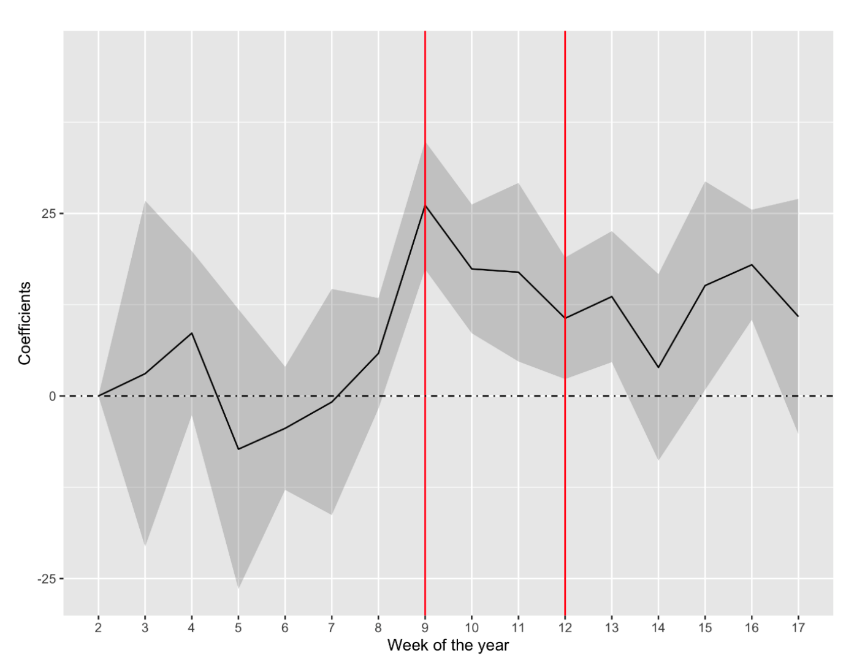

Figure 2 below shows our estimates on the evolution of the difference between the distance travelled weekly in German-speaking Switzerland and that travelled in the French-speaking cantons (Ticino is excluded because the measures adopted were more restrictive and prolonged than in the rest of the country). In the weeks prior to the outbreak, cantons in both linguistic regions had more or less similar mobility patterns. Soon after the first hotspot was identified, however, we observe important elements of divergence: the effect of German culture on mobility becomes visibly positive and remains such throughout the emergency period. Overall, the fall in average distance travelled daily has been notably lower in the German speaking part of the country.

Figure 2: Difference in mobility between German and French-speaking Swiss cantons

Note: Week 9 refers to 24 February-1 March, while week 12 refers to 16-22 March. The date of the outbreak was 25 February and the implementation of federal measures took place on 16 March. Figure compiled by the authors.

Why cultural identity matters

The evidence of significantly different responses across linguistic areas to measures adopted by the Swiss government homogenously across the whole territory suggests that cultural identity matters. Our empirical model allows us also to evaluate the effect of some specific traits that characterise the culture of German-speaking Switzerland, such as the high degree of interpersonal trust diffused in the population and a lower tolerance for state interventions in the economy. Both are negatively associated with mobility reductions (i.e. compliance) during the various phases of the pandemic.

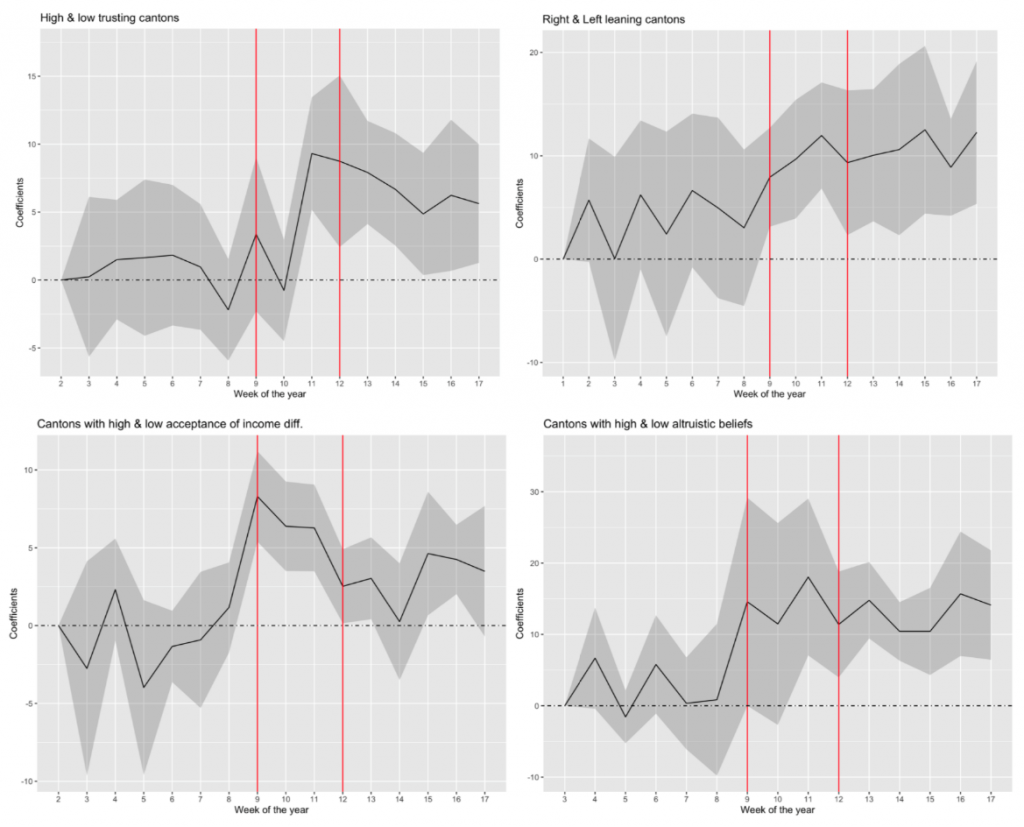

Figure 3 focuses on some indicators of these cultural traits and shows, for each of them, the difference between the distance travelled weekly in cantons above the sample median and that travelled in cantons with values below this threshold. The first panel at the top left, for example, shows how prior to the outbreak, there is no significant difference between cantons characterised by high and low levels of interpersonal trust, but the divergence in mobility patterns between the two groups becomes significantly positive after the identification of the first Covid-19 case in the country (phase two) and remains significant up until week 13 of phase three.

Figure 3: Average difference in weekly mobility (average distance travelled daily) in Swiss cantons

Note: Week 9 refers to 24 February-1 March, while week 12 refers to 16-22 March. The date of the outbreak was 25 February and the implementation of federal measures took place on 16 March. Figure compiled by the authors.

This is not surprising. Reducing mobility, in fact, becomes less relevant as an instrument to reduce the probability of contracting the disease if one believes that the rest of society will respect, among other things, physical distance and other infection prevention and control norms. In a sense, physical distancing replaces social distancing. Similarly, in a cultural context that focuses on individual success and where the rebalancing of public interventions is hardly tolerated, it is reasonable to expect that the population will be more reluctant to comply with measures that entail serious limitations on personal freedoms.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Brent Schumer (CC BY-NC 2.0)

_________________________________

Neha Deopa – Graduate Institute

Neha Deopa – Graduate Institute

Neha Deopa is a PhD candidate at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva.

–

Piergiuseppe Fortunato – UNCTAD

Piergiuseppe Fortunato – UNCTAD

Piergiuseppe Fortunato is a Senior Economist at the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD).