European Administrative Networks are networks of national actors who interact to improve the implementation and enforcement of EU policies. Drawing on new research, Dorte Sindbjerg Martinsen, Reini Schrama and Ellen Mastenbroek illustrate the role and structure of these networks, together with some of their key limitations.

Despite being the core executive of the European Union, the European Commission has limited competences when policies are to be implemented and enforced in the member states. To compensate for this executive deficit, the Commission employs an extensive set of tools to monitor and ensure compliance with EU rules. Infringement procedures are undoubtedly the best known and most researched among these tools.

European Administrative Networks (EAN) are an increasingly popular instrument for filling this gap in the European Administrative Space, however, they have received less academic attention. European Administrative Networks are networks of national administrative entities such as ministries or agencies, which interact to improve the national implementation and/or enforcement of common EU policies. Their importance as tools of governance has been highlighted by the Commission in its Better Regulation agenda from 2017 and recently in its Action Plan for Better Implementation and Enforcement of Single Market Rules. But how do they function and do they manage to bring their members together on how to improve the application of EU rules? In an ongoing research project, we explore and aim to explain the role of EANs.

Interaction as a key premise

Interactions are a core feature of networks, and an essential premise for their effectiveness. For networks to matter, their members need to interact. In two recent studies, we have assessed whether interaction takes place and the extent to which domestic institutions, i.e., welfare and healthcare institutions, condition such interaction.

Our research aims to bridge and contribute to two strings of literature that do not often meet: literature on new modes of governance in EU implementation and enforcement and the literature on welfare typologies. We are interested in the extent to which national institutions structure how national administrative organisations engage with their European counterparts. However, existing welfare typology research is insufficient for this purpose as it mainly covers the EU-15 or a selected set of OECD states. Therefore, in order to examine networked welfare governance in its current form, we decided to update welfare and healthcare cluster analysis, covering the EU-27 plus the United Kingdom, Norway and Iceland.

Networks as apolitical forums?

Existing literature tends to portray network interaction as conducive to integration and implementation. The literature presents that since EAN members are civil servants, often acting as experts, the networks constitute relatively apolitical forums. Surrounded by other experts, members act without the strings of politics, acknowledging interdependence and thus the necessity to interact. Furthermore, the dominant assumption seems to be that interaction will happen across the board and members will learn from the diversity brought together in the network.

However, an emerging string of literature looks to domestic institutions and political factors as structuring such interaction. This insight is relevant to our studies of network interactions, as national welfare and healthcare systems reflect different institutional and political choices. We thus assume that these differences inform network members and make them selective as to which other peers are relevant to approach and interact with.

EU welfare and healthcare networks

In one study, we examine interaction patterns in one of the EU’s oldest administrative networks established in 1958, which deals with welfare across borders for EU citizens: the so-called Administrative Commission for the Coordination of Social Security Systems.

In this administrative network, bureaucrats from all EU member states interact frequently to exchange views and solve problems related to cross-border welfare. The network has extensive competences: 1) facilitating uniform application of Community law, 2) issuing recommendations and making decisions on how to apply EU regulation in practice, 3) settling administrative disputes between member states, and 4) preparing legislative proposals for reforming the rules on cross-border welfare.

Our second study examines network interactions between national civil servants in the Cross-Border Healthcare Expert (CBHC) group, set up as part of the Patient Rights Directive. Here we deal with a much younger network, operating in a policy area marked by member states’ reluctance to delegate competences to the supranational level and based on a directive with mixed purposes and vague formulations. The members of the network have to experiment their way forward and find the common denominator.

Welfare and Healthcare Cluster Analysis

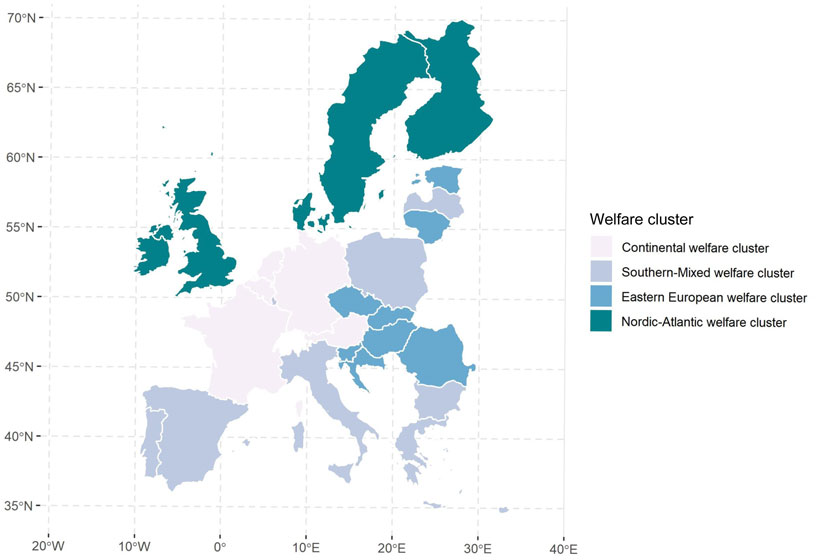

To explain interactions in these two networks, we performed two cluster analyses, portraying the welfare and healthcare typologies of contemporary EU. Our welfare cluster analysis of the Administrative Commission was performed for the EU-27 plus the UK. We identified patterns of institutional similarity among EU member states on the basis of three key fiscal welfare state attributes: 1) quantity of welfare provided, 2) type of financing and 3) investment in welfare services. The welfare indicators for the individual EU member states can be found here.

As shown in Figure 1, we identified four welfare clusters in the contemporary EU. The first is a continental welfare cluster, composed of Germany, the Netherlands, France, Austria and Belgium, and characterised by relatively high total social expenditures as a percentage of GDP, financed mainly by contributions and displaying a relatively low level of welfare services. The second cluster is the Nordic-Atlantic welfare cluster, characterised by a relatively high level of welfare services and primarily tax-based financing. Sweden, Finland, Denmark, the UK, Ireland and Malta belong to this cluster. Although the UK, Ireland and Malta score lower on total social expenditures as a percentage of GDP than their Nordic counterparts, they nevertheless fall into this cluster because they share a relatively high service emphasis and tax-financed welfare.

The Eastern European welfare cluster, thirdly, includes Slovenia, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia, Estonia, Lithuania and Romania. This group of countries has thus far remained largely unmapped. It is interesting to see that they represent a distinct welfare cluster. In this cluster, total social expenditures as a percentage of GDP are low and mainly contribution financed. There is, however, a certain relative service emphasis. However, this is indeed a relative measure drawn on the basis of benefits in kind as a percentage of total social benefits. The fourth and final cluster is the Southern-Mixed welfare cluster, which includes Italy, Greece, Spain, Portugal and Cyprus as well as Luxembourg, Poland, Bulgaria and Latvia. This welfare cluster is characterised by relatively low total social expenditures as a percentage of GDP, the lowest score on service emphasis across the four clusters, and its welfare is primarily contribution-financed.

Figure 1: Welfare clusters in the EU and UK

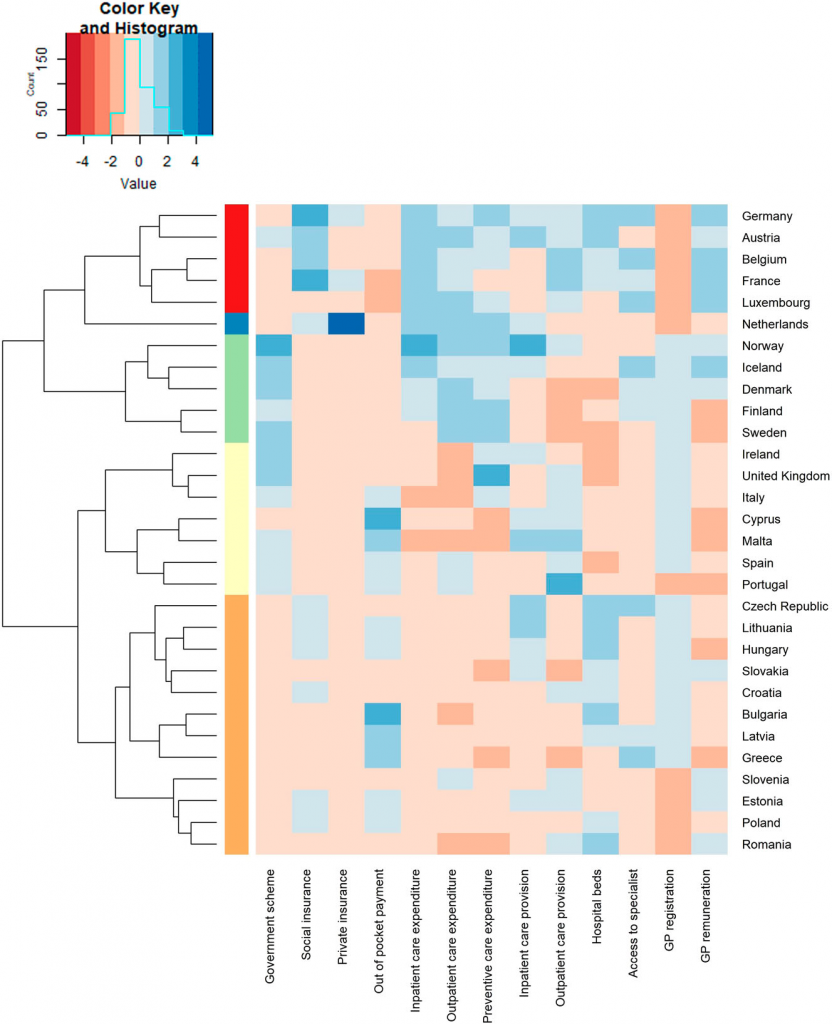

Turning to our healthcare cluster analysis, we conducted this for the EU-27 plus the UK, Norway and Iceland. The cluster analysis is based on indicators of financing, expenditure, and provision of and access to healthcare – the raw data for the healthcare indicators can be found here.

We identified five healthcare clusters, which are presented in Figure 2 below. First, a cluster of elaborate social insurance healthcare systems, including Germany, Austria, Belgium, France and Luxembourg. Second, a cluster of limited social insurance healthcare systems, containing the Czech Republic, Lithuania, Hungary, Slovakia, Croatia, Bulgaria, Latvia, Greece, Slovenia, Estonia, Poland and Romania. Third, a cluster of limited public healthcare systems, incorporating Ireland, the United Kingdom, Italy, Cyprus, Malta, Spain and Portugal. Fourth, a cluster of elaborate public healthcare systems, which includes Norway, Iceland, Denmark, Finland and Sweden. And finally, the Netherlands forms a distinct elaborate hybrid healthcare cluster. Figure 2 presents the healthcare clusters as a so-called ‘heatmap’, with blue denoting high values and red denoting low values, scaled in the colour-key.

Figure 2: Healthcare cluster analysis

Social Network Analysis

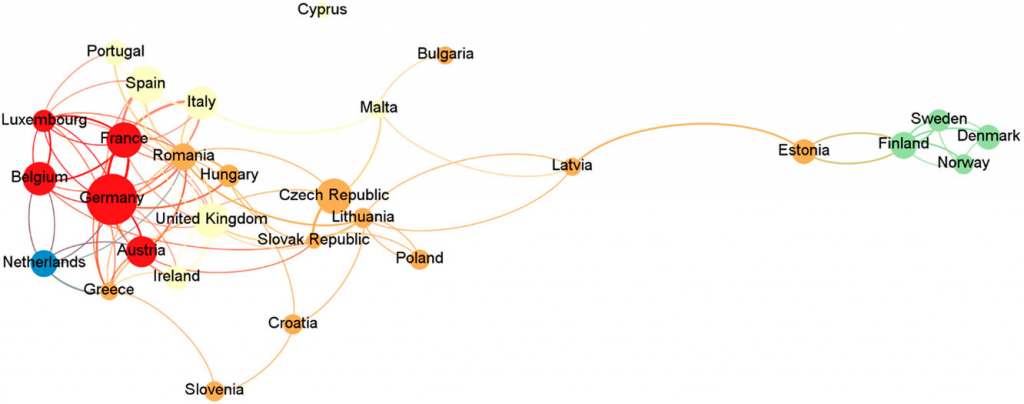

To examine network interactions, we used social network analysis on the basis of collected survey data on the exchange of information, advice and best practices within the networks. The surveys were distributed among all network members, each member organisation receiving one survey. For the welfare network analysis, we got a 100% response rate. For the healthcare analysis, the response rate was 87%. Based on these data, we developed an Exponential Random Graph Model to describe interactions and test the extent to which these are conditioned by domestic policy institutions, as captured by the welfare and healthcare typologies.

For both networks, we found that interactions do take place across the board. Network members do relate to another, exchanging information, best practices and advice. At the same time, we found the interactions turned out to be clustered. For the cross-border welfare network, we found that domestic institutional and political factors indeed structure network interaction. When interacting, peers mainly seek out peers from similar welfare typologies. The finding for healthcare was similar: institutional differences condition patterns of interaction in the Cross-Border Healthcare Expert group – to an even larger degree than in the Administrative Commission. In particular, the Nordic states tend to stay by themselves, connected to the network only by their Baltic counterparts, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Network graph of interactions in the Cross-Border Healthcare Expert group

Implications

Our network analyses have several overall implications. They show, firstly, that domestic institutions condition interactions and thus the extent to which learning across institutionally diverse members takes place. It also shows that some actors are more central and better positioned to navigate the networks examined than others.

Central actors are powerful actors with more opportunities to set or shape the agenda and put a stamp on the future course of the policy, its implementation and enforcement. They exchange information, best practices, and advice more frequently, thus having more leeway to define the way forward. Other actors remain more at the margins of the network, with less access to the core resources exchanged.

Although European Administrative Networks are increasingly important governance tools, their members neither engage nor benefit evenly from this type of co-operation. Uneven interaction implies that although EANs are important tools to improve the implementation and enforcement of EU rules, they are mainly so for the core of the network whereas its periphery may be left largely unaffected by the interaction of its European counterparts. It also implies that the full potential of learning is not realised, their added value limited by institutional similarities.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying papers in the Journal of European Public Policy and the British Journal of Political Science

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Jonatan Svensson Glad (CC BY-SA 2.0)