The decades-old dispute between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the region of Nagorno-Karabakh has been reignited, with forces fighting for the two sides engaged in intense fighting since the end of September. Christopher R. Rossi writes that the recent escalation might prompt a reassessment of the ‘soft law’ approach embodied by the Minsk Group, which was formed from the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) in 1992 to mediate over the conflict.

Did the metaphor ever aptly fit? The ‘frozen conflict’ between the ethnically Armenian and Christian inhabitants of the breakaway enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh and the Muslim-majority neighbouring Azerbaijan has once again melted. A torrent of cross-border hostility not seen for a quarter-century burst forth in late September, with concerns of inundating the wider region in ethnic enmity and historical memory.

Behind the gate of the Line of Contact stand Russia in support of Armenian interests (with delicately balanced Azerbaijani interests, as well), and Turkey in support of Azeri interests. Reports of Turkish-recruited Syrian mercenaries and substantial upgrades to the Azeri arsenal, including the deployment of attack (as opposed to reconnaissance) drones and electronic war systems, add tactical and technological advancements that again draw into question the ice-entombed description of the conflict as frozen.

If it is more apt to refer to this conflict as unresolved rather than frozen, it may be worth questioning the actions of the Minsk Group, which was formed from the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) in 1992 to mediate if not monopolise stewardship over the conflict. This closed group, composed of France, the United States, and Russia, has been unable to broker a negotiated solution and currently has been criticised for its glacial approach to visionary thinking, its pathological commitment to secrecy, and its artful vagueness except in terms of wanting to keep the violence from spreading.

Some of the criticisms relating to the Minsk Group’s inaction focus on the many cross-cutting energy, trade, and security interests affecting major power interests in the overlapping neighbourhoods of the South Caucasus. The complicated effects of the Armenian diaspora add texture and complexity to the Minsk Group’s mission, and to the domestic politics of the three principal co-chairs.

However, asymmetric relations within the Group may also account for its inability to broker a settlement. Observers perceive Russia as outmanoeuvring the other principals, delicately nurturing interests on both sides of the Line of Contact while benefitting more from the low-grade conflict than its resolution. The United States and France may recognise that their out-of-region status secures for them more influence only by maintaining their seats at the negotiating table to monitor and check Russian interests as much as to secure a meaningful resolution to the conflict.

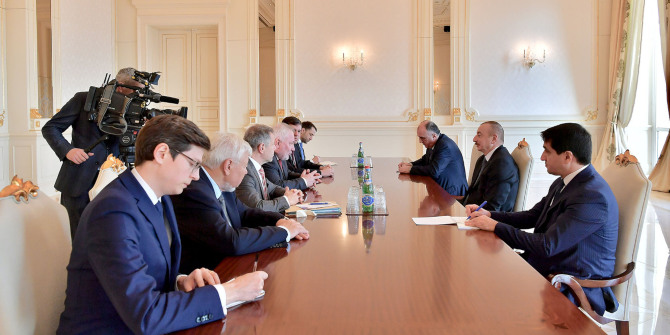

Ilham Aliyev, President of Azerbaijan, receiving OSCE Minsк Group co-chairs at a meeting in 2019, Credit: President.az (CC BY 4.0)

The Minsk Group has received praise for articulating a roadmap for peaceful settlement with the 2007 Madrid Principles. These principles called for returning of the illegally seized territories surrounding Nagorno-Karabakh to Azerbaijan, guaranteeing Nagorno-Karabakh’s security and self-rule, establishing a corridor linking Armenia to Nagorno-Karabakh, forging a pactum de contrahendo, whereby the parties commit to the future peaceful resolution of Nagorno-Karabakh’s final legal status, re-establishing the rights of all internally displaced persons, and providing for security and international peacekeeping operations. These principles provide the structure to which the Minsk Group and the warring parties need to return. The inability to return to the Madrid Principles indicts the status of the soft law formula created by the OSCE.

International relations specialists debate the repositioning of sovereignty as something more than a territorially-based power system. Historically, that power system revolved around states and the status conferring privileges of Eurocentric decision-making that developed out of Roman law’s idea of the father of the household (patria potestas) and the feudal concept of grandeur (majestas). Sovereignty produced a system dominated by Great Power relations, which increasingly turned toward a process of multilateralism in the twentieth century.

Some theorists have noted a postmodern estrangement with the process of multilateralism, which in decision-making forums proved cumbersome, formalistic, and structurally asymmetric. New status-conferring and mission-centric arrangements arose out of diplomatic ‘coalitions of the willing.’ Such examples include Troikas, Wise Men, the G8, IGAD, the Arctic 5, the Six and Three-Party Talks about arms control on the Korean Peninsula, and the United Nations Group of Friends, and, of course, the Minsk Group.

Soft law forums were intended to shift the centre of gravity away from the formalistic and legislative workings of multilateralism. They called on a process of norm socialization that promoted flexibility, informality, comity and compliance in a way that deliberately minimised the publication or formalisation of obligations and standards to which states would be held. Soft law meant to sidestep the calculations of loss aversion theory, where diplomats might worry more about changes to policies that result in potential losses more than the acquisition of equivalent gains. Soft law forums were meant to stimulate problem-solving rather than instantiate diplomatic rigor mortis.

The misperceived frozen conflict of Nagorno-Karabakh has much to do with the hardening of the soft law process internal to the Minsk Group. The Minsk Group’s avoidance of the strictures of institutional fixity and transparency proved valuable in terms of creating the Madrid Principles, on which any future resolution of Nagorno-Karabakh’s fate needs to be based. However, its inability to capture advantages of relevant advocacy, normative standard-setting, agenda-setting, and persuasion led observers away from the metaphor of Nagorno-Karabakh as a frozen conflict, and toward the sclerotic metaphor of the Minsk Group as a soft law entombment of coronary heart disease.

For more information, see the author’s paper on this topic in the Texas International Law Journal

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: President.az (CC BY 4.0)