Covid-19 has led to a spike in unemployment across Europe. Dennis Tamesberger and Johann Bacher write that while some job losses may be temporary, policymakers should be concerned about the rise in long-term unemployment during the pandemic. Drawing on the case of Austria, they highlight the lasting impact long periods of unemployment can have on individuals.

It is well known that long-term unemployment increases with some delay after a recession. After the Great Recession, in the EU28, the share of the long-term unemployed in total unemployment shot up from one-third to one-half between 2008 and 2013. Long-term unemployment is mainly a consequence of permanent demand shocks but it can also be partly explained by a ‘hysteresis effect’, where rises in unemployment persist over time.

The duration of unemployment steadily reduces chances of reemployment because of the negative impact of unemployment on psychological and physical health, on the person’s skills and because of stigmatisation by employers. Even though the wage penalty caused by former unemployment is well proven, it seems to be particularly harsh for the long-term unemployed.

The Austrian case

Austria seems to be an interesting case because it draws on a wide variety of different policies to achieve full employment. Since the 1970s, there has been a political commitment by Austrian governments towards fiscal policy-orientated full employment. Budget deficits have been accepted to solve oil price shocks, to keep unemployment low and to develop the Austrian welfare state. For a long time, Austria had a relatively good overall labour market situation by international comparison.

However, since the last crisis, the performance of the Austrian labour market has weakened. In particular, long-term unemployment increased continuously from 2011 to 2016, reaching the highest value in 2016. To tackle the increasing long-term unemployment rate in the country, the Austrian government introduced a public employment programme known as Aktion 20.000 in July 2017; which can be seen as a forerunner of a job guarantee. The aim was to create 20,000 publicly subsidised jobs. Despite the positive effects of the pilot period, Austria stopped the planned expansion of the pilot phase.

Covid-19 and long-term unemployment

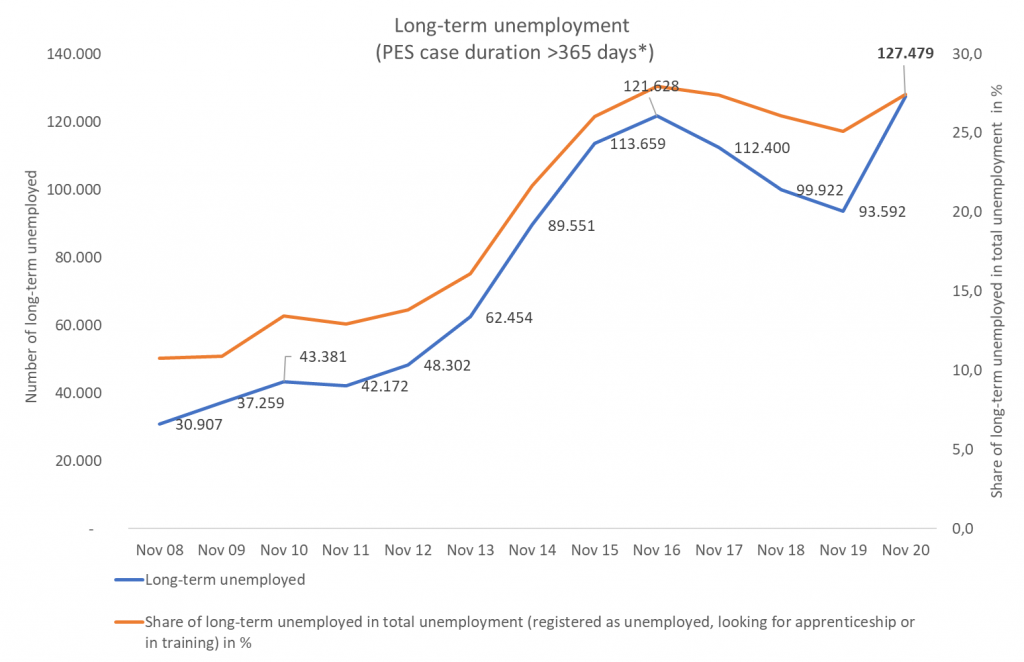

In November 2020, the number of longer-term unemployed people was 127,479, an increase of 36.2% in comparison to the previous year. In absolute terms, this was the highest number of long-term unemployed people in the history of Austria. But long-term unemployment has also become a more serious problem in relative terms. In 2008, around 10.8% of all unemployed people (registered as unemployed, looking for an apprenticeship or in training) were categorised as long-term unemployed. At the moment, more than a quarter (27.4%) of those who are unemployed have been without work for more than a year.

Figure 1: Development of long-term unemployment in Austria

Note: The chart is based on the indicator ‘langzeitbeschäftigungslos’ (long-term jobless). Under this definition of long-term unemployment, all unemployed people with a case duration of more than 365 days, who have not taken up a job for more than 61 days, are included. Source: Public Employment Service (PES), authors’ calculations.

The main victims

The risk of long-term unemployment increases with age. In Austria, around 55% of the long-term unemployed are over the age of 44. However, 4.4% of the long-term unemployed are young people. More men than women suffer from long-term unemployment and 31.8% of the long-term unemployed are non-Austrian citizens. This is below the proportion of migrants in total unemployment (34.4%), which indicates that migrants have a higher risk of becoming unemployed, but that the unemployment duration is shorter for migrants. One reason is that on average migrants are younger than non-migrants which makes it easier for them to find a job.

Figure 2: Socio-demographic characteristics of the long-term unemployed in Austria

Source: PES, authors’ calculations.

Around three quarters (76.6%) of the long-term unemployed have low levels of education, having at most finished compulsory education or a dual apprenticeship. Despite this, some 18.4% of the long-term unemployed have further or even higher education. This means that a lot of potential is not being tapped into and qualifications are devalued by long-term unemployment. Another specific characteristic of long-term unemployment is the high proportion of people with health-related employment limitations or with disabilities.

Long-term impact

Unemployment has negative economic, social and psychological consequences for those affected and for society, as Marie Jahoda found in her synopsis of research on unemployment in the early 1980s. These findings are still valid today, especially for long-term unemployment. For those affected, long-term unemployment leads to a loss of income and, as a consequence, results in a higher risk of poverty; it entails a reduction in social contacts and a deterioration in health. These scars are visible over the long term, i.e. they can still be observed once the person has succeeded in returning to the labour market.

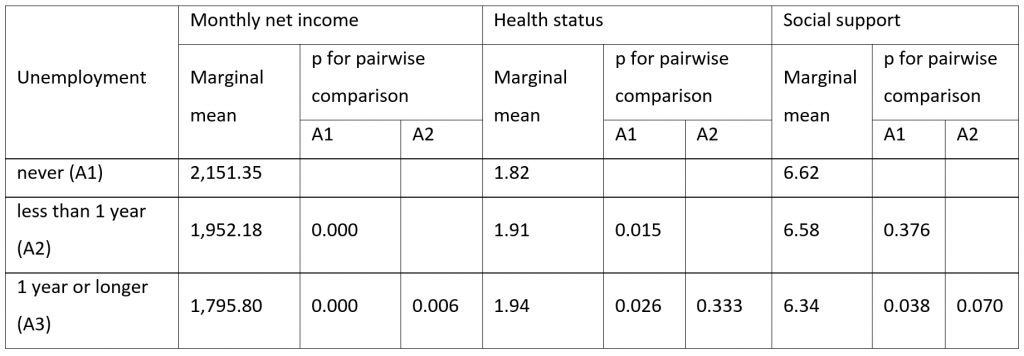

On the basis of the Social Survey Austria 2016, employed persons with previous, long-term unemployment experience of a year or longer earn an average of €356 net per month less than respondents who have never been unemployed, even if they are employed in the same industry and to the same extent, do the same job or do not differentiate between gender, age, education, partnership, children and place of residence. They also tend to report less social support (networks, supportive environment, etc.) than people who have never been unemployed or have been unemployed for less than one year. Finally, the long-term unemployed also suffer from a significantly poorer state of health, but in this aspect only differ from those in employment who have never been unemployed.

Table 1: Income, health status and social support by unemployment

Note: n(monthly net income)=775; n(health status)=1,161; n(social support)=1,161. Health status=subjective evaluation by respondent with 1=very good to 4=bad. Social support=index of eight items that measure social support in different situations, like knowing someone who will help the person move house, lend them money or discuss problems with them. The index varies from 0 (no help in any situation) to 8 (help in all eight situations). Source: Austrian Social Survey 2016, only employed respondents.

Conclusions

Considering the extent of the problem and due to the expected further increase in (long-term) unemployment due to the pandemic, measures to tackle long-term unemployment are crucial. From our point of view, the following strategies are expedient.

First, reducing income loss during unemployment and thus reducing the risk of poverty should be a key priority. Second, more staff should be employed under the Public Employment Service (PES). There is already evidence that lowering caseloads can decrease the duration of unemployment as well as increase the reemployment rate. Finally, there should be an effort to create jobs for the specific needs of the long-term unemployed by introducing a public job guarantee. The Austrian pilot project Aktion 20.000 proved successful in this regard and could be implemented again or mimicked in the shadow of the pandemic in order to mitigate its impact on the labour market.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: © AMS/Photo Studio B&G