Citizens with a strong attachment to their country are often assumed to be more likely to express opposition to the European Union. But is this always the case? Drawing on a new study, Leonie Huddy and Alessandro Del Ponte identify a clear difference between citizens with ‘nationalist’ attitudes and those who are ‘patriotic’. While nationalism is associated with an increase in Euroscepticism, patriotism appears to increase support for the EU.

Is nationalism on a collision course with the European Union? The emergence of successful right-wing neo-nationalist parties hints at this possibility. The German AfD, the French National Rally, the Danish People’s Party, the True Finns, the Italian Lega Nord, and others variously oppose free movement within the Schengen zone, a single European currency, and greater European integration. Neo-nationalist party leaders such as Matteo Salvini, Marine Le Pen, and Geert Wilders commonly pit national interests against those of the EU, referring to themselves and their supporters as ‘patriots’.

Before accepting that nation and Europe are necessarily at odds, it is important to recognise the existence of two distinct forms of national allegiance: nationalism and patriotism. Nationalism is typically defined as a sense of national superiority and dominance, a theme frequently pursued by neo-nationalist political parties as they rail against immigration, free trade, and the EU. In contrast, patriotism is understood as national pride and love of country, factors that can be marshalled in support of the EU. Emmanuel Macron explicitly linked patriotism and EU support when he said “I want to be the president of patriots against the threat of nationalists” following the first round of his successful 2017 bid for the French presidency.

Do national allegiances bolster or undermine EU support? And what determines the direction of their effects? To answer these questions, in a recent study, we analysed data from participants in 12 Western European countries included in the 2003 and 2013 national identity modules of the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP). In both years, the ISSP included a rich set of questions tapping different facets of national allegiance. The questions asked about support for different ethnic and civic conceptions of the nation, diverse facets of national pride, and national chauvinism. In a psychometric measurement model, all 25 survey items loaded onto one of two factors: nationalism and patriotism.

We then analysed the political effects of nationalism and patriotism, making several new discoveries in addition to confirming a number of prior findings. The data confirm that nationalism and patriotism are highly correlated – especially after accounting for measurement error – but that they have divergent effects on attitudes towards globalisation and support for the EU. Patriotism enhances support for the EU, immigration, and free trade, whereas nationalism promotes EU opposition, anti-immigrant attitudes, and protectionism.

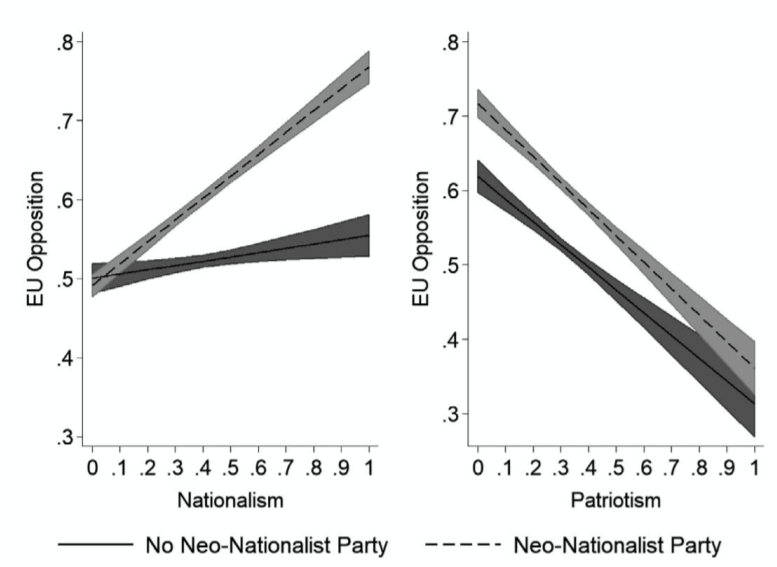

Of greater importance, the data offer new insights into how nationalism shapes citizens’ attitudes toward the EU. We discovered that the presence of a neo-nationalist party in a country affects how nationalism, but not patriotism, shapes support for the EU. In countries and years where a neo-nationalist party is present, nationalism has a much stronger effect on EU opposition than without such a party. In contrast, patriotism enhances EU support regardless of whether the country has a neo-nationalist party (Figure 1). In our analyses, a neo-nationalist party with strong national electoral support had even greater influence on EU opposition than one with a weaker vote share.

Figure 1: Effect of nationalism and patriotism on EU opposition by presence (dotted line) and absence (continuous line) of a neo-nationalist party

Note: Dark error bands represent 95% confidence intervals.

Second, in countries without a neo-nationalist party, less well-educated nationalists are more opposed to the EU than better-educated nationalists, reflecting the familiar association between lower educational attainment and EU opposition. In countries with a neo-nationalist party, however, EU opposition is equally strong among the most and the least educated nationalists (Figure 2, left and right panels). Even more strikingly, the most educated nationalists are almost four times as likely as poorly educated nationalists to vote for a neo-nationalist party.

Figure 2: Effect of nationalism on EU opposition by presence of a neo-nationalist party and level of education

Note: The charts display the predicted value of EU opposition. Dark error bands represent 95% confidence intervals.

These findings underscore that nationalist rhetoric is more important for EU opposition than rising levels of public nationalism, which have remained relatively constant in European countries over the past 25 years. Against this backdrop of emergent neo-nationalist parties and intensified nationalistic rhetoric, patriotism continues to shape support for the EU regardless of the presence of a neo-nationalist party within a country. In our analyses, the positive effects of patriotism on EU support are larger than the negative effects of nationalism.

Recent electoral results point to the resilience of pro-Europe parties when faced with increased nationalistic discourse. It remains to be seen, however, whether pro-Europe sentiment will prevail over the decade’s rising nationalistic tide. The European Union’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic may serve as a political bellwether; closing of borders and hoarding of vaccines hint at future divisive nationalism whereas a common stimulus package and open borders imply future patriotic unity.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in Political Psychology (co-authored with Caitlin Davies)

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: CC-BY-4.0: © European Union 2019 – Source: EP