Job retention schemes have helped Europe to avoid mass unemployment during the Covid-19 pandemic. Bernhard Ebbinghaus and Lukas Lehner write that while these schemes had an immediate impact during lockdown, the future development and long-term consequences of job retention policies remain uncertain.

With the Covid-19 pandemic, Europe not only faced an unprecedented public health crisis, but also a major threat to employment and earnings. During the first wave in 2020, the employment shock induced by lockdowns was ten times larger than during the Great Recession a decade earlier. Yet in contrast to the United States, Europe experienced only a moderate increase in unemployment since many European welfare states used short-time work schemes to retain workers in formal employment and avoid mass dismissals.

These job retention policies were quickly developed in spring 2020. Some European countries were able to scale up their established short-time work schemes, while others needed to innovate, such as the UK. Although the short-time work schemes used during the Great Recession offered a blueprint, the schemes adopted during the pandemic have been larger in scale and spread more widely across Europe. The EU’s Support to Mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency (SURE) fund has been pivotal in helping member states to finance short-time work.

Unprecedented usage of short-time work

Total hours worked fell by 12% across the OECD during the first wave of the pandemic. This was more than ten times larger than the drop in activity during the last quarter of 2008. In comparison to the Great Recession, when a ‘record-breaking’ 1.5 million short-time workers were counted across Europe, it is estimated that more than 40 million people were covered by short-time work arrangements in the EU by mid-2020. The largest schemes were provided by France (11.3 million), Germany (10.1 million), Italy (8.3 million) and the UK (6.3 million). These four major European economies all used short-time work to avoid mass unemployment.

Germany has a long history of using short-time work (Kurzarbeit) for seasonal labour in construction and for securing industrial jobs during downturns. About 1.1 million or around 5% of workers were in short-time work during the Great Recession. Short-time work benefits are administered by the employment office as part of earnings-related unemployment insurance for labour market insiders. While the established scheme provides 60% of gross earnings (plus 8% for a parent), the benefits were increased during the pandemic (by 10% from the fourth month, and by another 10% from the seventh month onwards), while collective agreements may provide additional benefits.

In contrast, the United Kingdom adopted a new Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (CJRS), which was created by the Treasury on 15 April 2020. The scheme was intended to end in October 2020, yet following a further wave of infections, it was hastily extended until March 2021. Breaking with its liberal credo, the CJRS is an earnings-related benefit of 80% for up to four months, thus going beyond the UK’s flat-rate unemployment assistance and the recent reform of Universal Credit.

Similar to Germany, Italy has an established short-time work scheme (CIG) with benefits for labour market insiders in industry at 80% of gross earnings. Yet, short-time work was extended by Covid-19 schemes for all sectors not yet covered, though the length varied between six to twelve months. Nearly half of all workers received benefits during the early and severe first lockdown in Italy. Meanwhile in France, almost every second worker was covered by ‘partial’ unemployment benefits (80% of gross wage for up to a year) during the first lockdown.

Not all European countries followed this model. Several Nordic welfare states relied on their automatic stabilisers, while the Baltic countries and some eastern European countries were reluctant to provide costly short-time work provisions, particularly in those countries that did not implement severe lockdown measures.

The trade-off between unemployment and job retention

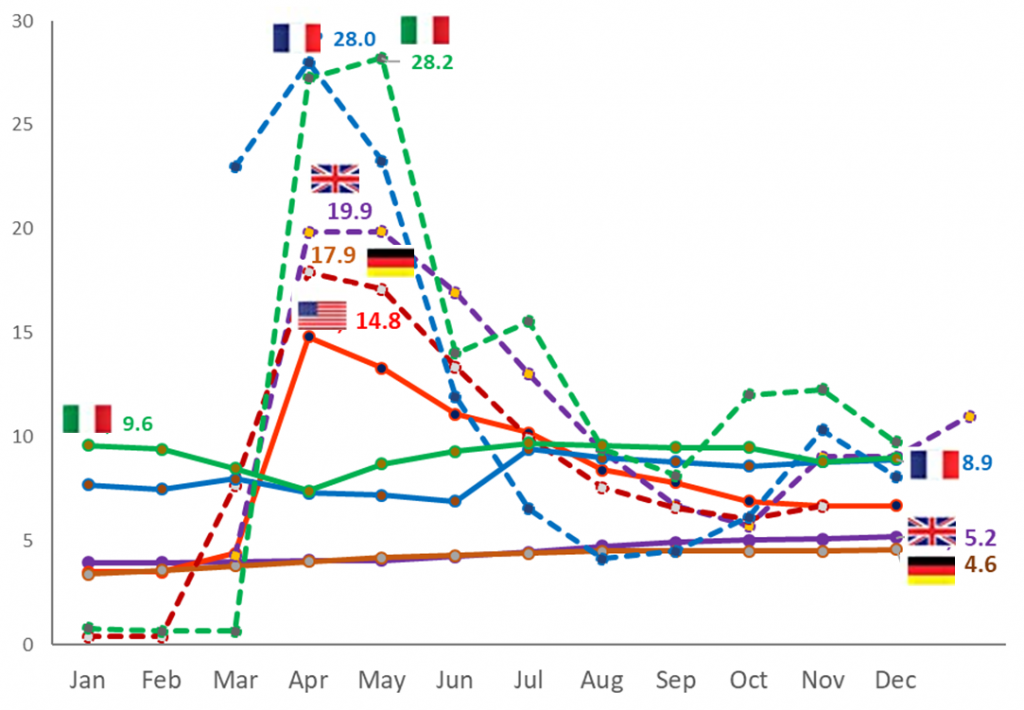

The US provides a counterexample of a flexible labour market and residual welfare state which during the first wave let unemployment skyrocket to nearly 15%. In contrast, European rates remained much lower and with more modest gradual increases (see Figure 1). Thanks to short-time work, mass unemployment was mitigated in the four major economies.

Figure 1: Unemployment rates in OECD countries and job retention rates in Germany, France, Italy and the UK (2020)

Note: Job retention rates (dashed lines) are our own estimates based on national short-time work statistics (Italy: estimated FTEs), not directly comparable to head count of unemployment (solid lines). Source: Own composition, OECD Employment Database, Eurostat 2021, and national sources.

The UK experienced a more substantial relative increase, but the job retention scheme has helped alleviate the employment shock and help business thanks to rather favourable conditions. The Continental European countries, most notably France and Italy with their severe lockdowns, relied heavily on their short-time work schemes and also implemented a ban on dismissals. Germany, which had less severe containment measures, experienced only a limited increase in unemployment thanks in part to the extension of its short-time work schemes during the first wave and beyond.

Instead of a rapid increase (and later decline) in unemployment as in the US, these four major European economies used short-time work to compensate business and workers and hoard labour, thus avoiding mass dismissals. The job retention rates (based on headcounts of those on full or partial furlough) are a flexible instrument compared to the dismissal and rehiring of staff. While France and Italy reduced their overall work volume (measured in hours) by around 20% in the first half of 2020, Germany and the UK reduced their work volume by 10% by the second quarter of 2020.

Although we cannot equate job retention (as it is variable by hours) and unemployment rates (a head count), it is clear that the flexible job retention schemes helped unemployment rates to be kept in check across most of Europe compared to North America. Job retention policies proved to be an effective policy in protecting workers against job losses, allowing a more flexible reduction of working hours among the workforce most affected by the pandemic.

The future of job retention?

Job retention schemes were initially envisaged as temporary measures, but they were extended with the reoccurrence of further waves and containment measures across Europe. During these subsequent waves, short-time work was nevertheless used in a more moderate way given containment measures tended to be less severe. Unemployment rates remained largely stable throughout this period.

Although Covid-19 vaccination rollouts have gained momentum in 2021, first in the UK and later in the EU, a third wave of containment measures during spring has posed a further challenge for businesses and jobs. Moreover, structural youth and long-term unemployment remain pressing problems, not least because opportunities for training during short-time work periods have often failed to enhance the employability of low-skilled workers and young jobseekers.

Job retention policies were at the heart of Europe’s crisis response and they have generated massive fiscal costs, contributing to an increase in public debt in many European countries. Within the Eurozone, public debt increased from 84% to 98% of GDP during the first year of the pandemic, reflecting additional health costs, welfare expenditure, and economic stimulus packages. Besides the associated cost, opponents have argued that job retention schemes hamper fluid turnover in labour markets and slow down structural adjustment if they are used for too long.

Supporters of job retention schemes emphasise the importance of preventing scarring effects from unemployment following mass dismissals. They also argue that labour hoarding allows for a quicker recovery as workers remain in employment relationships. Faster economic growth would also help pay back public debt. Moreover, short-time work includes an important equity aspect as it spreads the costs of working time adjustment more evenly compared to layoffs concentrated on some (often vulnerable) groups of workers.

As Europe emerges from its public health crisis, severe social and economic consequences are likely to last for the foreseeable future. Job retention provided a successful short-term but costly remedy to compensate for lockdown measures. European countries relied on their automatic stabilisers and job retention policies to avoid mass dismissals. Not least due to the EU’s SURE funding, a new European consensus has emerged to institutionalise rapid response measures during crises, and this will serve as a blueprint for the future. Establishing more permanent short-time work tools could ultimately be part of a broader reform to prepare for future crises and strengthen Europe’s social model.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Patrick Robert Doyle on Unsplash