When people are reminded of the social isolation of lockdown, they behave more selfishly than they otherwise would, find Sabrina Jeworrek and Joschka Waibel. This has important implications for a world in which in-person interaction is becoming rarer.

Social distancing is a powerful tool to counter the spread of COVID-19, and much effort has already been devoted to studying why individuals (voluntarily) comply with it. Based on a large sample of almost 90,000 individuals from 39 countries, Ludeke et al (2020) show that perceived local social norms successfully predict individual social distancing behaviours ― the greater the perceived consensus on the importance of social distancing in a given area, the more people complied with the rules. The question, however, of whether social distancing can in turn affect either the perception of social norms, or norm compliance, has not been answered yet.

By conducting two online experiments with about 500 German students and using the priming method to activate social isolation recollections, we show that the experience of isolation does not change normative beliefs about whether pro-social behaviour is appropriate (or selfish behaviour is inappropriate). It does, however, change the willingness to comply.

In both experiments, participants were randomly allocated into two groups. In the so-called priming group, participants initially answered questions about their personal experiences and feelings during the national lockdown (November 2020 to April 2021) in Germany. The control group were asked unrelated questions to elicit sociodemographic information and personality traits. Next, all participants were given an abstract economic decision problem:

An individual and a charity each receive the same amount of money (five euros). The individual can override this equal split by keeping some or all of the donation to the charity themselves, or by giving some or all of their handout to the charity.

In the first experiment, participants had to judge how socially appropriate the choices in this situation were, following the incentivised method proposed by Krupka and Weber (2013). The results show no difference between the groups’ normative assessment of taking (or giving) money from (or to) the charity.

In order to understand whether the willingness to comply with social norms changed due to the experience of social distancing, a second experiment was conducted with a new sample of students. Here, participants actually did split the money between themselves and the charity. Almost half behaved far more selfishly than the socially appropriate norm would dictate, and decided to take an average of EUR3.81 from the charity. Furthermore, individuals who were primed by their own memories of social isolation before taking the decision and who said they had felt isolated during lockdown behaved more selfishly. They took more money from the charity than non-primed participants did.

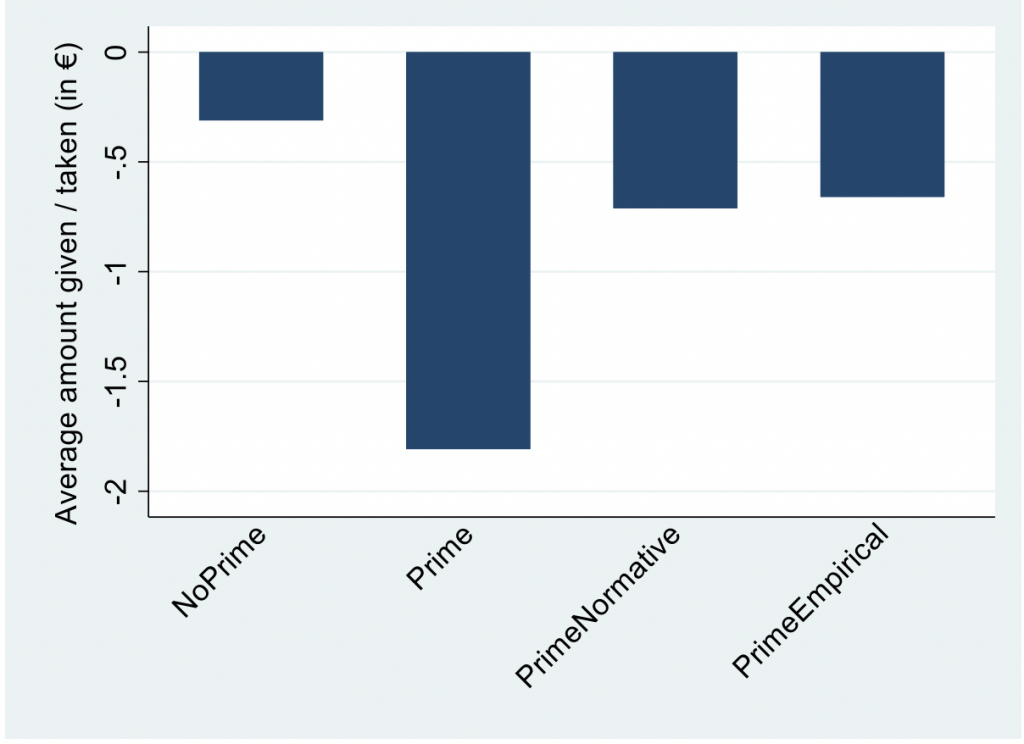

However, this negative effect can be mitigated. We manipulated both the empirical expectations of how other participants behaved, and the normative expectations of what behaviours others approved in a similar situation. As a result, we observed a decline in the average amount taken from the charity. Primed participants behaved almost like the non-primed ones.

Figure 1: Overview of results

Note: NoPrime: n= 45; Prime: n = 47; PrimeNormative: n = 52; PrimeEmpirical: n = 47.

Our study reveals a causal relationship between the perceived social isolation experienced during the pandemic and selfish behaviour in an artificial allocation setting (but with real payoffs). It is important to note that both experiments took place at the end of May 2021, in an area with rapidly declining incidence rates and the premature suspension of the “nationwide emergency brake” (Bundesnotbremse). Persistent social distancing does indeed cause a decline in prosociality, even after the relaxation of social distancing rules and the reopening of shops and restaurants, and at an optimistic time. This suggests that these behavioural distortions may be long lasting.

More positively, even long term social isolation (of about six months) does not seem to substantially change the basic norms we uphold. Our study also underlines the value of highlighting exemplary behaviour (e.g. voluntary work or fundraising), as it can serve as a powerful buffer for the less obvious behavioural damages caused by social distancing in times of crisis. However, this might only work if the erosion in norm compliance is not yet broadly visible. Bicchieri et al (2020), for example, have shown that observed violations of the norm have much more effect on individuals’ willingness to comply than observed norm compliance does. In other words, if people see others breaking the rules, they are more likely to break them themselves – as Matt Hancock may have realised.

Our findings also address a more general danger of social isolation in the post-COVID world. As social interactions become more digitalised, in-person interactions are likely to decline. For example, the software company SAP has already announced it is giving its employees complete freedom of choice on where to work. Daily time spent on social networking has increased from 90 minutes in 2012 to 145 minutes in 2019. Future research should try to understand how much in-person interaction might be necessary to prevent the impending behavioural damages caused by (perceived) social isolation.

Note: This article was first published by the LSE’s COVID-19 blog. It is based on an IWH Discussion Paper, Alone at Home: The Impact of Social Distancing on Norm-consistent Behavior. The article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Sasha Freemind on Unsplash