Angela Merkel will step down as German Chancellor following the country’s federal elections on 26 September. But what direction might Germany’s EU policy take in the post-Merkel era? Minna Ålander, Julina Mintel and Dominik Rehbaum assess what lessons can be learned from the main party manifestos.

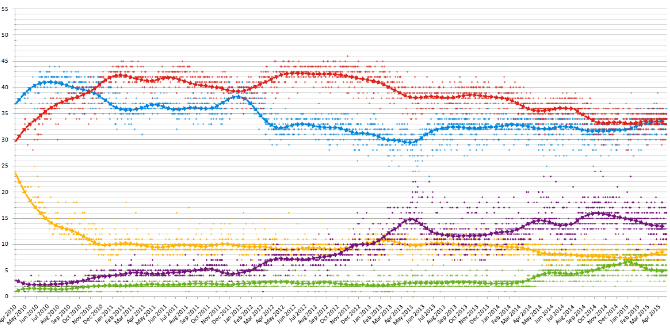

The German political landscape has changed substantially over the past decade. While the once dominant catch-all parties have gradually lost voters and members, the formation of the right-wing Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), the re-election of the neoliberal Free Democratic Party (FDP) to the Bundestag in 2017, and the rise of the Greens have diversified politics in the German parliament.

As Angela Merkel’s fourth and final term comes to an end, voters will have to decide at the federal elections in September on whether to continue along a familiar path or instigate profound change. But given Merkel’s central role in European politics over the past decade, the choice of Germany’s next leader will also have significant consequences for the EU. The main party manifestos that have been published prior to the election give a first insight into what this impact might be.

Federal, national, or supranational?

When it comes to Germany’s position within the EU, the electoral manifestos suggest there are currently three distinct camps among the six parties that are likely to be represented in the Bundestag. The current governing coalition of the Christian Democrats (CDU/CSU) and Social Democrats (SPD) consider the EU to be a central part of Germany’s future. Yet, despite the rather ambitious EU chapter in the coalition agreement they negotiated in 2017, few concrete projects have been implemented. Although both parties have made a strong pledge to the EU, their current manifestos lack clear ideas for future EU integration.

Conversely, the Greens and the FDP both have a strongly pro-integration, federalist vision for the EU’s future. The Greens want to use the Conference on the Future of Europe as a starting point on a path to a Federal European Republic, and the FDP envisions a decentralised federal European state as the final destination of EU integration.

Finally, the left-wing Die Linke and the right-wing AfD differ from the other political parties in their explicit criticism of the EU. Die Linke is critical of the EU for what it views as a fondness for neoliberalism and austerity. It would like to replace this approach with more focus on public investment initiatives and to cut all funding for military projects. In contrast, the AfD would like Germany to leave the EU altogether.

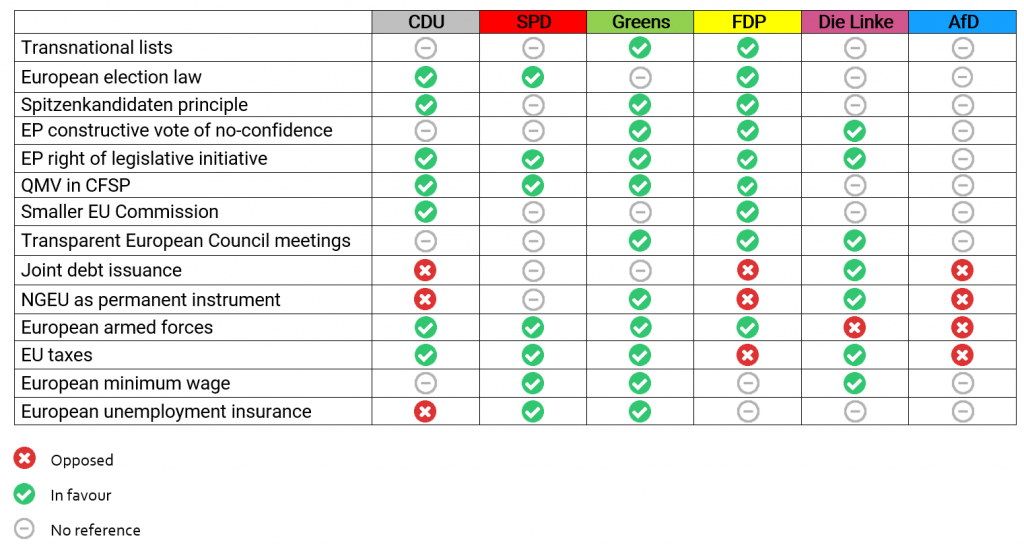

EU institutional reform

With the exception of the AfD, all of the main parties want to extend the competencies of the European Parliament through a formal right of legislative initiative. While the CDU/CSU, the Greens and the FDP explicitly support the Spitzenkandidaten procedure, only the latter two mention transnational lists in their manifestos. The CDU/CSU and the SPD express support for a model of common European suffrage but remain vague on what this entails. Meanwhile, Die Linke proposes that EU Commissioners and the European Council President should be directly elected by the European Parliament.

Overall, all of the main parties favour reforming the EU’s treaties. Only the AfD has refrained from addressing treaty reforms beyond its demand that Germany should exit the EU. The Greens and the FDP explicitly suggest initiating treaty change through the Conference on the Future of Europe, while Die Linke mainly wants to enable more public sector financing. The CDU/CSU do not regard treaty change as an end in itself but as a possible instrument to enhance the EU’s capacity to act.

EU foreign and security policy

Regarding foreign and security policy, all parties with the exception of the AfD favour introducing Qualified Majority Voting (QMV) to enhance the EU’s decision-making capacity. The FDP, CDU/CSU and SPD support a European Defence Union and the creation of a European armed forces. However, only the FDP explicitly outlines a model for a potential European army under parliamentary control.

All three parties simultaneously emphasise their commitment to NATO as the key pillar of European defence. The CDU/CSU manifesto envisions a core Europe (Bündnis der Gestaltungswilligen) in all matters of foreign and security policy within the scope of Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) and the European Defence Union.

Die Linke, in contrast, proposes to dissolve NATO and the European Defence Agency and rejects calls for a European army. The AfD would like to see an end to the European External Action Service and the Common Foreign and Security Policy. The two parties thus stand in clear opposition to mainstream views on EU foreign policy in Germany.

Table: Stances on key EU policy issues in 2021 German election manifestos

Source: Compiled by the authors.

Die Linke also states that European defence companies should stop the export of weapons or technology to authoritarian countries and that military cooperation through initiatives such as PESCO and the Coordinated Annual Review on Defence (CARD) should be terminated. The Greens and the SPD also demand new arms controls and disarmament initiatives, as well as civil conflict prevention, while the CDU/CSU sees arms exports as a constitutive part of security policy and wants to promote common European arms projects and procurement.

Among Europe’s neighbours, the UK is singled out as the most important non-EU partner. However, all parties (except the AfD) emphasise that EU standards should not be degraded to enable cooperation. On Russia, Die Linke and the AfD advocate a positive approach and an end to sanctions, while the other four emphasise that current sanctions cannot be lifted as long as Russia continues the illegal annexation of Crimea and military action in Eastern Ukraine. The Greens and the SPD commit to advancing the integration of the Western Balkans, while the FDP seeks to terminate accession talks with Turkey. For the CDU/CSU, the unity of the EU-27 must be guaranteed before further enlargement.

Economic and Monetary Union

Although there is some measure of consensus on the need for future investments at the European level, only the Greens and Die Linke want to increase the EU budget. In their view, the EU’s Recovery and Resilience Facility should be integrated into the EU budget to enable democratic control and used as a permanent mechanism for investing in areas of importance for the future. The CDU/CSU and FDP, in contrast, reject the idea of making the recovery instrument permanent, while the AfD has warned that the creation of a ‘transfer union’ could ultimately lead to the demise of European economies. Meanwhile, the SPD is seeking to use the recovery instrument to advance the integration process and create a true fiscal, economic, and social union.

The positions of the parties on taxation split along different lines than in the other policy fields. Here, the Greens propose introducing EU taxes on plastic and digital companies alongside a carbon border tax. The CDU/CSU and FDP support the harmonisation of national corporate taxes and the CDU/CSU joins the Greens, the SPD and Die Linke in proposing an EU financial transaction tax. Both the AfD and the FDP, however, are categorically opposed to any EU taxes.

The FDP and the CDU/CSU stress the need to reform the Stability and Growth Pact and to introduce sanctions for member states that are consistently in breach of the criteria, with immediate entry into force after the Covid-19 pandemic. Both parties also advocate the introduction of an insolvency procedure for states. The SPD wants to instead transform the Pact into a new sustainability pact.

The Greens and the FDP share the goal of transforming the European Stability Mechanism into a European Monetary Fund, albeit with different goals: the FDP wants to equip this new ‘EMF’ with the power to oversee the recipient member states’ compliance, while the Greens envision it as issuing non-conditional short-term credits to avert speculation against individual states. While the CDU/CSU, the Greens and Die Linke all favour the introduction of a digital euro by the European Central Bank to guarantee means of payment, the AfD proposes a return to a national German currency.

Key lessons

The main German election manifestos show that the German party landscape remains characterised by a pro-European consensus. The AfD has attracted a great deal of attention as the first openly anti-EU party in the Bundestag. Yet, the other political parties remain fundamentally positive toward EU integration, albeit with some reservations in relation to the Eurozone and fiscal policy in the case of the CDU/CSU and the FDP.

It is exceptionally difficult to predict the outcome of the election, but the most likely scenario is that the CDU/CSU will remain in power with a new coalition partner. One such coalition would be an agreement between the CDU/CSU and the FDP. This would likely oppose any mutualisation of European debt, as well as looser fiscal policy. It would lean toward deregulation and potentially reduce the pace of EU economic integration. In contrast, a coalition of the CDU/CSU and the Greens may well use the present momentum behind climate policy initiatives to push for more capacity for the EU to act in the realm of foreign policy.

Alternatively, should the CDU/CSU fail to remain in government, there would likely be a more substantial change in Germany’s EU policy. A coalition of the Greens, the SPD and Die Linke would almost certainly initiate a stronger shift toward social and climate policies, including a European minimum wage and increased public investment. However, Die Linke’s foreign policy positions, as well as the party’s relatively low polling numbers, may make such a coalition impossible. The same stands for a so called ‘traffic light’ coalition between the Greens, SPD and FDP, though here economic policy is likely to be the major sticking point.

At present, the polling presents a mixed picture and it remains unclear what direction Germany will take as it enters the post-Merkel era. It will be up to German voters to decide on whether the country should continue to pursue a similar path under a new leader, or whether it is time to initiate a major break with the past.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: European Council