There are some striking differences in how European leaders have explained the Covid-19 pandemic to their respective audiences. Drawing on a new study, Amrita Narlikar and Cecilia Emma Sottilotta show how these narratives reflect the policy responses that governments have pursued since the first wave of infections.

The Covid-19 pandemic has wreaked human and economic devastation on a global scale. But European governments – even with roughly similar political structures, cultures, and development levels – have reacted very differently to this existential policy challenge, sometimes with life and death consequences. These differences in policy responses need explaining, and a key to understanding them may lie in narratives.

Robert Shiller defines a narrative as ‘a simple story or easily expressed explanation of events that many people want to bring up in conversation or on news or social media because it can be used to stimulate the concerns or emotions of others, and/or because it appears to advance self-interest.’ Narratives matter because they help shape the fears, hopes, and expectations of people. They matter especially when tough choices have to be made, for instance in the context of international negotiations, and evidence suggests they matter more than data per se, especially amidst conditions of high levels of uncertainty.

The pandemic presents such a case. The SARS-COV2 virus, by definition, was a novel virus. Much confusion and conflicting advice surrounded the disease in the first months of 2020. In this context, narratives played a key role that the literature on crisis management in the public sector defines as ‘meaning making’: to help their audience understand the extent of the challenge to be tackled, political leaders formulate a storyline providing a convincing account of what is happening, why it is happening, what can/should be done about it, how and by whom.

At the very onset of the pandemic, some European leaders immediately voiced strong concerns about the possible economic fallout of the crisis, some did not. Similarly, some leaders presented the threat more narrowly as a disease that would affect ‘only’ certain sub-groups severely rather than society as a whole, some did not. Moreover, some governments introduced early and stringent restrictions, others did not.

The relationship between narratives and policy choices

In a recent study, we hypothesise that there might have been an inverse relationship between a narrative that emphasised the economic cost of the pandemic and suggested that the disease was a threat ‘only’ to certain sub-groups on the one hand, and the tendency to introduce early and stringent restrictions on the other.

To test our hypotheses, we analysed a total of 90 speeches delivered by national leaders in the 15 pre-2004 EU member states (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxemburg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and the UK) in February-April 2020. We relied on the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT) to study the policy response and classify it as ‘early stringency’ or not.

We used the variable ‘Econ’ to describe whether or not heads of government emphasised the economic rather than the human costs of the pandemic, for instance presenting policy decisions as informed by a trade-off between protecting public health via restrictive measures and ‘saving the economy’. The value ‘1’ was assigned to cases in which such emphasis was present, the value ‘0’ when it was absent.

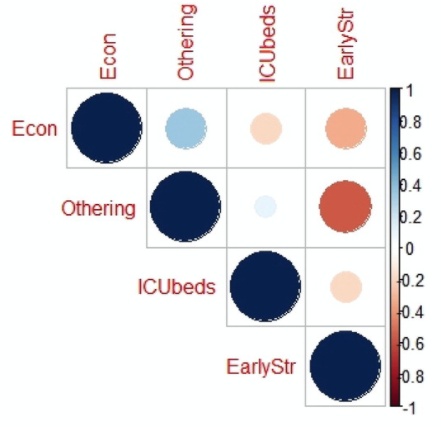

The variable ‘Othering’ describes whether or not the government narrative presented the threat as a problem that would affect ‘only’ certain sub-groups severely rather than society as a whole. The value ‘1’ was assigned to cases in which such framing was present, the value ‘0’ when it was absent. We also included a control variable that we deemed to be potentially relevant: whether or not the number of Intensive Care Unit (ICU) beds was above average in the countries analysed (see Figure 1). In the early phase of the emergency, policy-makers were assessing their countries’ situation not only through the absolute number and growth rate of total cases, but also via the country’s provision of ICU beds. We assumed that governments that had high ICU bed capacity might have placed less emphasis on the potential human costs of the pandemic.

Figure 1: Correlation matrix of responses to Covid-19 in European countries

Note: The size of each circle indicates the extent to which variables are correlated (a larger circle means a higher level of correlation). The colour of the circle indicates whether this correlation is positive or negative.

The empirical results summarised in Figure 1 support our hypotheses. As the correlation matrix shows, both ‘Econ’ and ‘Othering’ are inversely correlated with the early introduction of restrictions to contain the spread of the virus (‘EarlyStr’). In other words, when leaders emphasised economic costs in their narratives, policy responses lacked early stringency.

While all governments involved in the management of the Covid-19 crisis showed awareness of the deleterious economic consequences that the pandemic would entail, not every head of government spelled out the belief that there could be a trade-off between protecting public health and avoiding an economic downturn. Leaders such as Dutch PM Mark Rutte and British PM Boris Johnson presented the human cost of the pandemic as inevitable, introducing restrictions relatively late compared to other policy-makers such as Finnish PM Sanna Marin, who presented the economic cost of the pandemic as inevitable instead and introduced restrictive measures early on.

By the same token, the responses to the pandemic lacked early stringency when governments such as those in France and Spain presented the threat more narrowly, suggesting that the disease would affect ‘only’ certain sub-groups severely (e.g. the elderly and the vulnerable) rather than society as a whole.

A comparison of Sweden and Greece

The development and evolution of the pandemic narratives and policy responses can be better appreciated by taking a closer look at two cases: Sweden and Greece. In addition to being comparable in terms of population size and share of urban population, they both defied expectations in the first wave of infections in contrasting ways. Months into the pandemic, Greece had been presented by international media as an ‘unlikely success story’, while Sweden, whose health system is characterised by large financial and human resources, and whose ‘moderate’ approach had been initially praised by the WHO, ended up being criticised for its shortcomings.

The narrative developed by the Swedish government had several key features. First, it insisted on the need to introduce voluntary measures that would be proportional and sustainable, based on the assumption that the total number of victims at the end of the pandemic would have been the same regardless of the restrictions imposed. Second, it placed emphasis on the need to isolate ‘at risk groups’ to protect them. Third, it was characterised by the prominent role of technocratic, administrative authorities in guiding government action.

In contrast, the narrative adopted by the Greek government was strikingly different. First, it framed government action as a deliberate choice to prioritise human lives over the economy, introducing stringent measures intended to preserve public health until a vaccine or a treatment could be found. Second, it insisted on the need to protect ‘at risk groups’, but with a strong emphasis on intergenerational responsibility of the youth vis-à-vis the elderly, who often live in the same household. Finally, the narrative was characterised by a high level of personalisation, with the use of an emotional register and comparisons with other countries.

Conclusion

The results of our study shed light on the urgent need for scientific advisors and policy-makers to understand the importance of narratives in the policy-making process. While we have focused on the early phase of the pandemic, we believe the relevance of our analysis has only increased. Governments continue to muddle along, clustering around the spectra we identified, and people continue to die or suffer the debilitating effects of long Covid.

Some uncertainties have indeed been resolved. We now know, for instance, that the disease is airborne. But new ones have emerged, chiefly in relation to the effectiveness of vaccines against existing and potential new variants. Amidst these uncertainties, if governments are to stand a chance in countering vaccine hesitancy, resistance to masks, and preventing needless deaths, their leaders would do well to pay greater attention to their own narratives.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying article in the Journal of European Public Policy

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: European Council