Italy’s Five Star Movement has now been in government for over three years, but the party still defies easy classification. Drawing on a new study, Antonio Benasaglio Berlucchi examines how the party is defined by its electoral base.

The emergence of the Five Star Movement (M5S) as Italy’s largest party in the 2018 Italian general election was seen by many as the de facto end of the country’s ‘Second Republic’ – a period of alternation in power between the centre-left and centre-right coalitions which followed the demise of the once dominant Christian Democracy party and the other parties involved in the early 1990s Tangentopoli corruption scandals.

These scandals were uncovered by a series of judicial investigations, popularly known as mani pulite (clean hands), which ultimately led to the collapse of Italy’s ‘First Republic’. However, the mani pulite investigations did not result in the end of widespread corruption in Italy, nor did they reduce the salience of corruption issues in the subsequent Second Republic.

Following Silvio Berlusconi’s arrival as a prominent figure in Italian politics in 1994, much of the political scene became sharply polarised around his actions. A clear moral divide developed between Berlusconi’s supporters, who viewed him as a self-made businessman at the service of the country, and his opponents, who saw him as the epitome of corruption and incompetence.

This opposition of values was the breeding ground for the first major success of the Five Star Movement in the 2013 Italian general election. Founded in 2009 by the comedian Beppe Grillo and the entrepreneur Gianroberto Casaleggio, the M5S seized the opportunity offered by the then centre-left government’s failure to present a viable alternative to Berlusconi, capitalising on widespread distrust toward established politics and general discontent among the public amid the 2008 financial crisis.

Beyond its flamboyant anti-establishment rhetoric and general claims of moral superiority, the Five Star Movement’s self-proclaimed post-ideological character and its pervasive ambiguity on substantive issues such as citizenship, minority rights and European integration challenge conventional party classifications. This ideological ambivalence, which in a recent study I describe as ‘populism without host ideologies’, became self-evident after the 2018 election when the M5S initially formed a government with the far right League only to later join an alliance with the centre-left Democratic Party (PD).

For a party that has built its electoral fortunes on presenting itself as the champion of onestà (honesty) and clean politics, and whose raison d’être has been the rejection of political compromise and collusion, this shift came as a surprise to many, even in a country where trasformismo (political transformism) has long been a pervasive feature of politics.

A catch-all populist party

The Five Star Movement’s change in coalition partners raises important questions about the ideology and value preferences of the almost one third of Italian voters who supported the party in 2018. First and foremost, does the party adhere to the far right ideas promoted by the League, or has it established itself as a new left alternative to the mainstream PD? Rather than looking at the ways in which the Five Star Movement’s representatives have framed or justified the party’s controversial U-turn, I focus my analysis on evaluating how the M5S is defined by its electoral base.

Answering these questions is important not only because of the significant role the Five Star Movement now plays in Italian politics, but also due to the party’s impact on the future of Italian democracy. Indeed, understanding the Five Star Movement’s success helps shed some light on whether the anti-establishment sentiments present in Italy have predominantly left-libertarian roots (as seen in some inclusive forms of populism in other southern European countries) or, conversely, whether we are witnessing an illiberal turn among Italian voters.

To help provide an answer, I conducted a quantitative assessment of populist sentiments among Italian voters using survey data. I identified two distinct dimensions, which I labelled ‘anti-politics’ and ‘exclusionary attitudes’. I then employed these measures to predict the vote for the M5S and the other parties in the 2018 election and to map the different ideological components within the main party electorates. My empirical findings challenge conventional views that M5S voters are generally closer to the centre-left. They suggest that the party’s ambiguity on social issues enabled it to attract a significant share of voters with exclusionary attitudes toward outgroups.

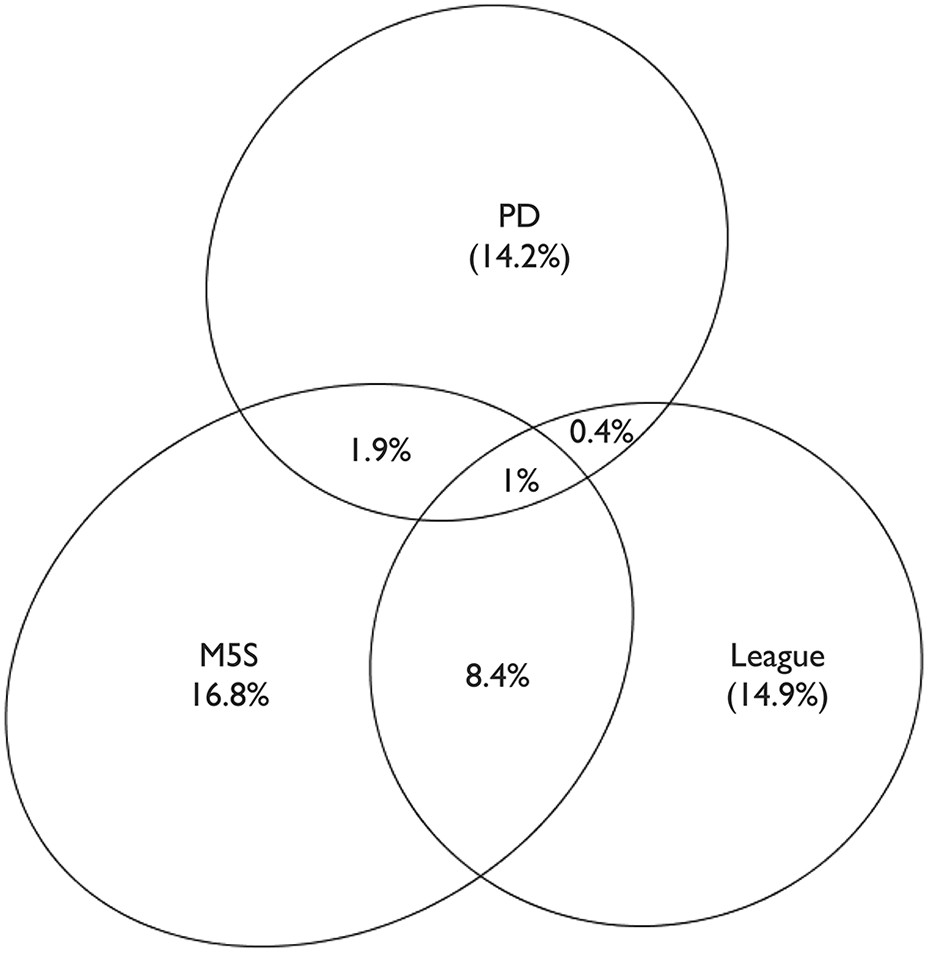

Indeed, most opinion polls confirm that the Five Star Movement’s decline since its entry into government has not benefited the left-wing and socially liberal parties, but rather the (radical) right-wing camp. While support for the PD and the other leftist parties has remained relatively stable since 2018, the M5S has lost more than half of its voters. The two parties who appear to have benefited most from this have been the League and the far right Brothers of Italy. Figure 1 below shows a visualisation of how the potential pool of Five Star Movement voters overlaps with potential voters for the League and the Democratic Party. Whereas the overlap between the M5S and the League’s potential electorates is relatively large, the share of PD voters who are also potential voters for the other two parties is much smaller.

Figure 1: Overlap of potential voters for the Five Star Movement, League and Democratic Party

Note: Author’s elaboration from www.cses.org, using the online application www.eulerr.co (Larsson, 2020).

Consistent with these trends, my empirical findings provide a picture of the M5S as a catch-all populist party whose voters harbour diverse and often conflicting value systems. The party represents a new brand of populism prêt-à-porter which fits all tastes and sizes, and which offers representation to any array of dissatisfied voters regardless of their value backgrounds.

The Five Star phenomenon is certainly puzzling for its unusual combination of vague populist appeals and ideological cherry-picking. However, I believe it is a full-fledged product of Italy’s Second Republic and the cultural transformations brought about by reactions to Silvio Berlusconi’s political agenda.

Berlusconi and Grillo may be sworn enemies, but their movements share a common thread. They each represent a brand of politics based on sensationalism rather than realistic programmes, a suspicion of experts, the rejection of the intermediary bodies of representative democracy, and the Manichean idea of an existential struggle between good and evil, where dissident voices are seen as traitors and political opponents are perceived as enemies. While the Five Star Movement’s emergence may have signalled a new era for Italian politics, it is one that nevertheless has a high level of continuity with the past.

For more information, see the author’s accompanying paper in Party Politics

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: European Council