Germany is a diverse society, but is this diversity reflected in the candidates who stand for election? Drawing on new research ahead of the German federal election on 26 September, Julia Schulte-Cloos finds there has been a general trend toward greater numbers of candidates from minority backgrounds, but this varies substantially between German parties.

According to official numbers, around a quarter of all Germans have a so-called ‘migration background’. Yet as in many other European countries, these minorities are barely represented among those in political office. Given that the presence of minorities in politics is viewed as a key factor in the substantive representation of the interests of minority groups, it is crucial to understand whether there is a trend toward more diversity among the candidates competing in German federal elections.

To shed light on this issue, I have analysed the ethnic diversity of all candidates that have stood in the past five federal elections in Germany, comprising some 22,711 candidacies between 2005 and 2021. Measuring a candidate’s ‘migration background’ is notoriously difficult. Some data can be directly measured by geo-coding the information on their place of birth as provided in the list of candidates published by the Federal Returning Officer. But the task becomes more complex if we try to go beyond simply looking at birthplaces.

To understand the potential discrimination faced by candidates from party gatekeepers and voters, it is useful to consider whether their background can be identified by others from their names. A candidate’s name is a piece of information that is directly available to voters when they encounter campaign posters, read a candidate’s name on the ballot paper, or see a candidate ultimately end up in office. Yet a complete analysis of the surnames of all candidates is an extremely challenging task and cannot feasible be done manually.

What’s in a name?

One solution is to adopt a ‘deep learning’ approach. Using a kind of artificial recurrent neural network known as ‘long short-term memory’, it is possible to perform an automatic classification of all candidates based on their surnames. I have put together such a model that classifies surnames according to a set of categories built on those available on Wikipedia.

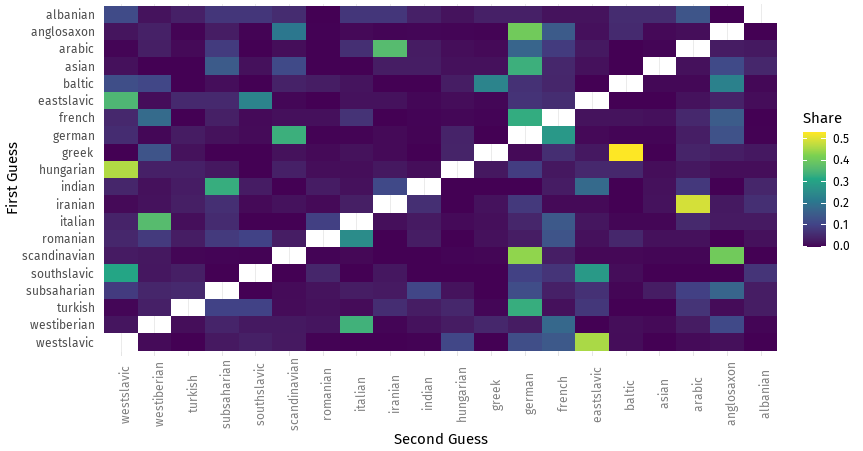

Figure 1 below gives an illustration of how the model attempts to classify names into these categories. The figure shows the relationship between the first guess the model produces when trying to classify a name and the model’s second guess. For instance, when the model’s first guess is that a name is of West Slavic origin, the second guess tends to be East Slavic. Similarly, when the first guess is that a name is Scandinavian, the second guess tends to be German.

Figure 1: Frequency of second guesses of a surname’s origin by first guess

Note: The figure shows the link between the model’s first guess (y-axis) and second guess (x-axis) when attempting to classify the origin of a name. The colour represents the frequency with which the second guess tended to be produced after the first guess.

Table 1 below illustrates the model’s performance by showcasing its classification of the three candidates for chancellor in the upcoming German federal election on 26 September: Annalena Baerbock of the Greens, Armin Laschet of the Christian Democrats (CDU/CSU), and Olaf Scholz of the Social Democrats (SPD). Laschet’s name is classified as French, reflecting the fact he has Belgian ancestors. However, as we are interested in the broader distinction between natives and candidates from minority backgrounds, we can pool all observations that are classified as Anglosaxon, Baltic, French, and Scandinavian into a broader category of ‘Northwest European’.

Table 1: Classification of the surnames of candidates for chancellor in the 2021 German federal election

Note: The table indicates the model’s first guess, second guess, and third guess when attempting to classify the origin of the candidate’s name.

Alongside this classification, I performed a manual analysis of the first names of candidates. Where information was available, I also took account of biographical information. The resulting classification closely corresponds to other available estimates on the number of minority candidates in the 2013 German federal election. To the best of my knowledge, my analysis of all 22,711 candidates that have stood in the past five German federal elections represents the most extensive attempt to automatically classify electoral candidates in this way.

Trends in minority representation by party

I define ‘minority candidates’ as those who are not within the ‘Northwest European’ group. Assessing the share of minority candidates over the past five federal elections, we can see a clear upward trend in their representation. While in 2005, only 4.4 percent of candidates standing for election had a ‘migration background’, this number now sits at 9.2 percent ahead of the 2021 federal election.

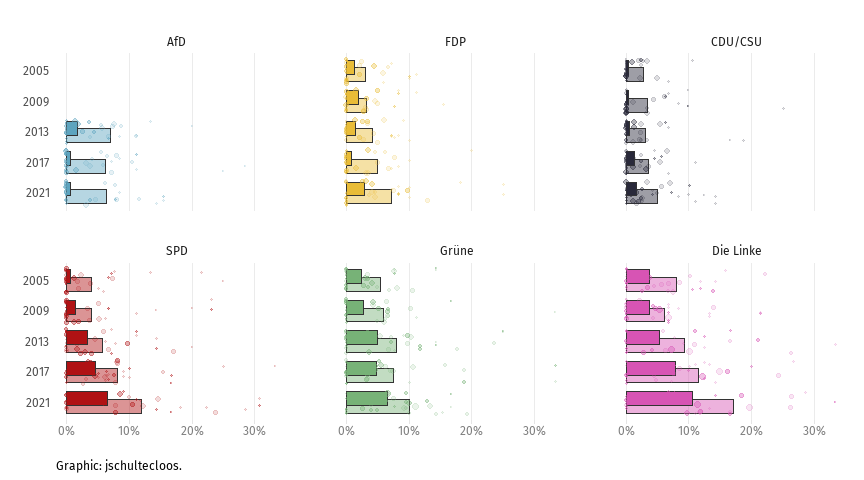

Critically, however, this positive trend is not present across all parties. Figure 2 shows the share of all minority candidates among the six biggest parties in Germany. We can clearly see the CDU/CSU has hardly increased their share of minority candidates over time. Instead, across all federal elections since 2005, only around 3.5 to 4 percent of candidates running for the CDU/CSU have been from a ‘migration background’. The party with the largest share of minority candidates has been Die Linke, with the 2021 figure being as high as 17 percent.

Figure 2: Share of minority candidates in German federal elections by party (2005-21)

Note: The figure shows the share of minority candidates across parties and time. Light shading indicates the total share of minority candidates, while dark shading shows the share of visible minority candidates.

To better differentiate between the origins of minority candidates, we can broadly distinguish between ‘visible’ and less visible minorities. I define ‘visible minority’ candidates as those coming from Muslim, Asian, and Sub-Saharan countries. Figure 2 shows the share of ‘visible minorities’ for each party, indicated by the darker bars in the chart. As can be seen in Figure 2, the vast majority of minority candidates running on the platform of parties located on the right (the populist right AfD, the neoliberal FDP, and the mainstream right CDU/CSU) seem to originate from European countries (including Eastern European countries). These parties have relatively few ‘visible minorities’ as candidates.

Top candidates

Although there is a general positive trend toward greater representation for minority candidates, the potential for these candidates to actually be elected depends critically on their position on party lists. The next question is therefore whether German parties place minority candidates among their top positions or whether these candidates are placed in positions where they are unlikely to win election.

To address this question, I looked at the share of minority candidates among the ‘top candidates’ found on a party’s state-specific list, namely the candidates that are among the top 25 percent of candidates for the two mainstream parties – the CDU/CSU and SPD – and among the top 15 percent of candidates for the four other main parties. I then compared the share of minority candidates among this subset with the overall share of minority candidates running for each party. If minority candidates are equally likely to be nominated among the top list positions, we should not observe a large discrepancy between these two measures.

Figure 3: Share of ‘visible minority’ candidates competing for elected office in Germany (2005-21)

Note: Light shading shows the share of visible minority candidates among all candidates. Dark shading shows the share of visible minority candidates among top list positions. Points indicate state-level averages that are smaller/larger according to the relative number of candidates running in a given state.

Figure 3 above shows, however, that this is hardly the case for most parties. The share of minority candidates among the top list positions tends to be smaller than we would expect from the overall share of minority candidates for each party. The Greens in 2013/2017 and Die Linke in 2021 are the only parties for which the share of minority candidates positioned among the most viable list positions substantively exceeded the overall share of minority candidates.

Party gatekeepers and political interest among ethnic minorities

While the underrepresentation of ethnic minorities among German candidates might result from discrimination by the party elites who decide on nominations, it may also be that those with a minority background have less interest in standing for election.

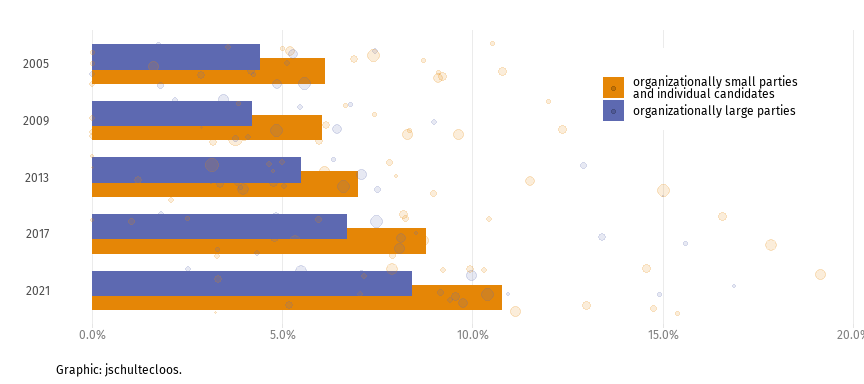

To shed light on this puzzle, I have compared the share of minority candidates among organisationally smaller parties with the share of minority candidates among larger parties. I define organisationally smaller parties as those that field fewer than 300 candidates in a given election. This corresponds roughly to the number of electoral districts in Germany and is half of the official size of the German Bundestag.

It is critical to note that parties regarded as being organisationally small under this definition cover the full ideological spectrum, ranging from small populist right parties such as the Liberal Conservative Reformers (LKR), to small Green parties such as the Ecological Democratic Party (ÖDP) and small radical left parties like the Marxist–Leninist Party of Germany (MLPD). There were also 610 individual candidacies that fell into this category.

If those from a minority background are more eager to participate in politics than their presence on the lists of organisationally large parties would suggest, we would expect to see a higher share of minority candidates among smaller parties. Indeed, Figure 4 below shows that this has been the case for the past five German federal elections, suggesting there is a potential ‘gatekeeper’ effect rather than a simple lack of interest in standing for election among ethnic minorities in Germany.

Figure 4: Share of minority candidates among organisationally small and large parties

Note: Points indicate state-level averages that are smaller/larger according to the relative number of candidates running in a given state.

These findings are encouraging as they imply there is interest in standing for election among those from underrepresented groups. It is also encouraging that over the five federal elections held between 2005 and 2021, there has been a clear positive trend toward more minority candidates. However, my findings also reveal that there are stark differences across parties, suggesting that not all parties are equally concerned about fostering this positive trend.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Mika Baumeister on Unsplash