Two opposition coalitions won a surprise majority at the Czech parliamentary election on 8-9 October. Jan Rovny writes the result represented a resounding victory for moderate opposition forces over the populist illiberalism of Prime Minister Andrej Babiš.

The 2021 Czech parliamentary election assumed the air of a referendum on the rule of Prime Minister Andrej Babiš. Babiš, a millionaire businessman accused of corruption and implicated in the recent Pandora Papers, campaigned in support of the common folk and against the purported vagaries of European unification, primarily associated with uncontrolled migration. The opposition primarily campaigned against Babiš.

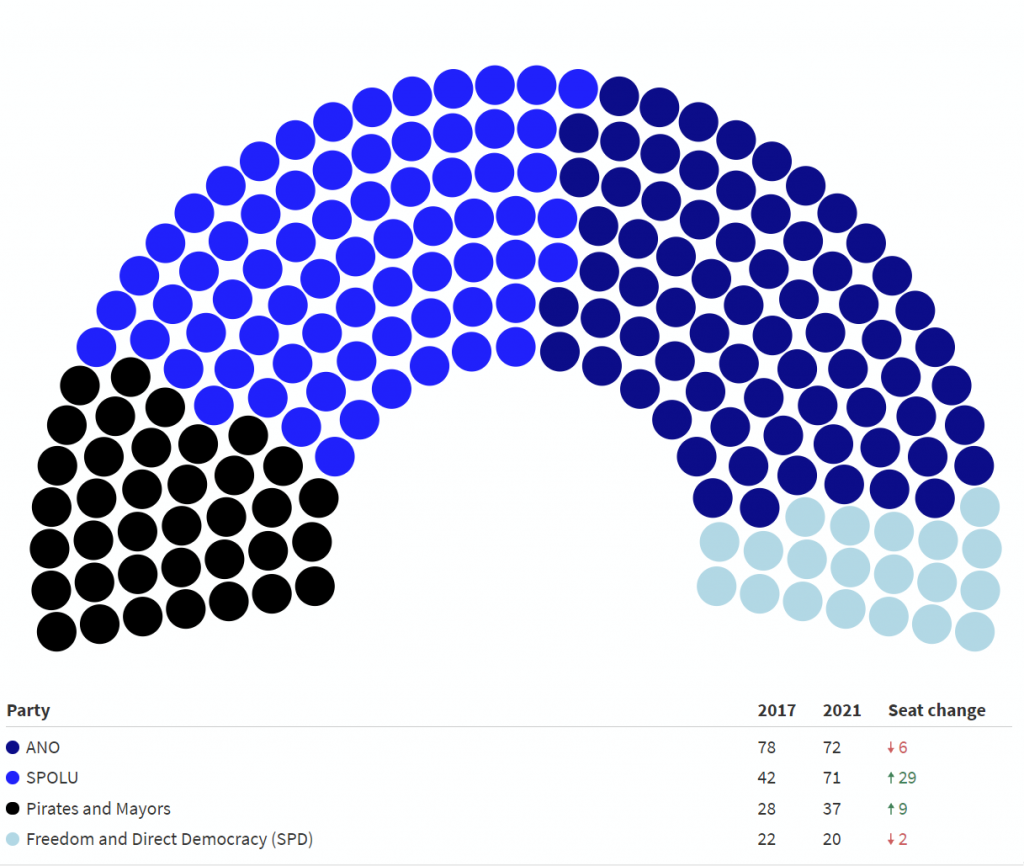

The knife-edge contest ended with a narrow victory for the opposition coalition SPOLU, uniting established right-wing parties, the conservative ODS and TOP09, and the Christian Democratic KDU-ČSL, with 27.8%. Babiš’s populist movement, ANO, came in a near second with 27.1% of the vote. However, given a new method for calculating parliamentary seats, ANO received one mandate more than SPOLU. The third party, with 15.6% of the vote, was the coalition of the social liberal Pirate Party and the centre-right Mayors and Independents (STAN). The last grouping to enter parliament was the radical right SPD with 9.6% of the vote.

Figure: Distribution of seats after the 2021 Czech parliamentary election

Note: Figure created with Flourish.

The election provided three important lessons on the effects of populism. The first lesson is the poisonous power of populism. By becoming the dominant figure of Czech politics, increasingly adapting the rhetoric and strategy of illiberalism, Andrej Babiš weakened his allies, and strengthened his opponents. While the outcome endows Babiš and ANO with the largest number of parliamentary seats, it leaves him in an impossible position to negotiate the next governing coalition, almost certainly paving the way for government turnover.

Second, the left has been left out, as historical left-wing parties recorded their worst electoral result and find themselves stripped of parliamentary representation. Finally, the election demonstrated that when democratic opponents of illiberalism put aside their differences and coordinate, they can defeat populism.

The poisonous power of populism

Andrej Babiš’s political movement, ANO, is a personalistic outfit with chameleonic tendencies. Initially built as an anti-corruption platform, it purported to bring apolitical pragmatism into politics. Mixing Babiš’s business profile with folkish overtones of hard work, it sought and succeeded to attract voters from across the political spectrum. Previously, ANO’s core characteristic revolved around atomised political proposals with no overarching political identity, under an official veneer of centrism. This was peppered with Babiš’s idiosyncratic outbursts against his opponents, against the EU, and against migration, adding a punchier, radical and illiberal edge to an otherwise smooth image.

Over time, the polished surface of ANO has lost its coating and the 2021 election campaign normalised Babiš’s outbursts. The movement’s programme opened with Babiš’s preface focusing on national sovereignty, opposition to the EU, heightened references to migration, and caricaturing the party’s political opponents. The campaign slogan of “until my body is torn apart” personalised Babiš as the defender of the common people to his last breath. Substantively, ANO’s programme was more focused on an increased role for the state in social affairs, infrastructure and security, combined with promises of balanced budgets and low taxes. ANO’s ethno-populist thrust, intertwined with a blurry marriage of social spending and fiscal frugality is reminiscent of western European radical right parties.

The previous parliamentary term saw the construction of an increasingly effective populist political bloc. The 2017 election left the governing ANO and electorally decimated Social Democrats short of a parliamentary majority, ultimately forcing them to rely on the votes of the communist KSČM. Giving communist parliamentarians indirect access to the levers of power breeched a taboo in a country where most people still remember the fall of the communist dictatorship as a monumental milestone.

In the ensuing years, Babiš sought to increase his influence over the courts, while ostentatiously cosying up to illiberal leaders like Victor Orbán. The decision to prop up the governing coalition with communist votes and the use of authoritarian tactics similar to those seen in Hungary and Poland, coupled with ANO’s erratic policies during the Covid-19 pandemic, had two consequences. It deepened the ideological, as well as the symbolic chasm between the government and opposition, and it clarified the position of ANO as a leftish and proto-authoritarian political force.

ANO, the biggest player in Czech politics, thus transcended its chameleonic veneer which had initially given it an ability to appeal left and right, and become unquestionably associated with illiberalism. Babiš’s attempts to acquire a firmer grip on power came at the cost of indirectly undermining his allies, and inadvertently mobilising his opponents.

Left out

The two historical left-wing parties, the social democratic ČSSD whose history reaches as far as 1878, and the communist KSČM that goes back exactly 100 years, recorded their worst ever results, leaving them without parliamentary representation. The ČSSD’s 4.7% undermines the party’s thirty-year dominance of the centre-left. The KSČM’s 3.6% was a bitter anniversary gift, ending a long parliamentary presence of this, once unopposed, leader of the communist regime.

Both parties have been overwhelmed by their own struggles, but they have also each succumbed to the populist orbit of ANO. The social democrats have been the core of centre-left politics in the Czech Republic since their electoral success in 1996. Recent years have, however, seen their electoral support dwindle, as their traditional working and public-sector middle-class electorates shifted. A battle for the soul of the party has played out between a liberal wing, seeking to turn toward more socially liberal politics centred on Europe, and a conservative wing which led the party into these elections in the tow of ANO and its illiberal and eastward-looking populism. The decision to follow ANO both in government and in the party’s political orientation has been disastrous for the party’s electoral appeal.

Meanwhile, from its heyday at the helm of the authoritarian regime, the KSČM has been reduced to a radical left protest party in the post-1989 democracy. Demographic replacement of its elder voters, nostalgic for communist regime certainties, has driven the party’s decline. However, the recent rise of cultural themes, centring on fears of migration advanced by the SPD and increasingly by ANO, has changed the substance of protest politics. The party’s core districts in the post-industrial northern regions have shifted allegiance to ANO and the SPD. Despite their opposition to migration and calls for a Czexit referendum, the historically Marxist KSČM has been unable to outmanoeuvre the SPD and ANO. The left’s dance with populism has proven to be a danse macabre.

Opening an opposition

The election ultimately represents a resounding victory for the moderate opposition forces which have managed to smooth over their differences and unite against populist illiberalism. The decisive anchoring of ANO in the left-authoritarian political space and the development of its illiberal bloc galvanised an unprecedented coordination of opposition forces. First, a new citizen initiative, “A Million Moments for Democracy”, organised a campaign of democratic meetings and demonstrations, the largest of which gathered an estimated 250,000 people, making it the biggest protest since the fall of communism. While explicitly targeting the conflict of interest and undemocratic tactics of Prime Minister Babiš, the initiative sought to educate, focus and unite democratically-minded citizens.

Consequently, in the runup to the 2021 election, moderate opposition parties became increasingly denoted as “democratic” parties. This stressed both their distance from the government and from its communist and radical right supporters and sympathisers, as well as their closeness to each other. Eventually, before the 2021 election five democratic parties formed two coalitions, significantly reducing the complexity of the political field.

The SPOLU coalition united mainstream conservatives and Christian Democrats with significant history and prior governing experience. The coalition focused on the traditional right-wing politics of fiscal responsibility, economic dynamism, and family-focused welfare. Despite prior tendencies of some of their members towards soft Euroscepticism, their programme was explicitly pro-European. The second democratic coalition united the social liberal Pirate Party, which effectively fulfils the political role of a Green party in the Czech party system and is supported by young and educated urbanites, with the locally rooted, centre-right Mayors and Independents, known by the acronym STAN. While presenting a well-rounded liberal programme, the coalition came under fire from Babiš for allegedly seeking to turn the country into “Piratostan”.

It is notable that five diverse parties managed to build two coalitions, combine their efforts, and gain a parliamentary majority. Their cooperation is a genuine success and a manual for the defeat of populists and illiberals that is now being emulated in Hungary. Simultaneously, their marriage is not even a marriage of convenience, but one of necessity. Intra-coalition rivalries were exemplified by the Mayors’ candidates seeking preferential votes to overtake their Pirate colleagues in the battle for parliamentary seats – a successful strategy that saw the Pirates lose 18 seats, while the Mayors gained 17.

Divided we stand

Prime Minister Babiš will do what he can to exploit these cracks. President Zeman, an ailing ally of Babiš, has already signalled that he will ask the leader of the largest party – not of the largest coalition – to form the next government, suggesting that Babiš will get one more chance. The parliamentary arithmetic, giving anti-Babiš forces an eight seat majority, is, however, insurmountable.

By solidifying the democratic camp opposed to Babiš, and by eliminating the traditional left from parliament, the 2021 Czech elections have concluded the reshaping of Czech political competition. Traditionally based on classical class divisions, Czech politics now follows the demarcation of many contemporary democracies.

Like its counterparts in the United States or in France, the new Czech parliament pits two opposing camps against each other. On one side stand the proponents of internationalism and cultural openness, embodied particularly by the Pirates and STAN. On the other is ethno-nationalist exclusion, utilised by Babiš and ANO, and personified by the radical right SPD. Rather than social class, today it is education and the urban-rural divide that determines the side one stands on.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: European Council

You entirely skipped the collapse of the Pirates and Mayors (cultural Marxist as Stan’s leader said…

Nice to see a swing back to responsible centre right and right-wing parties